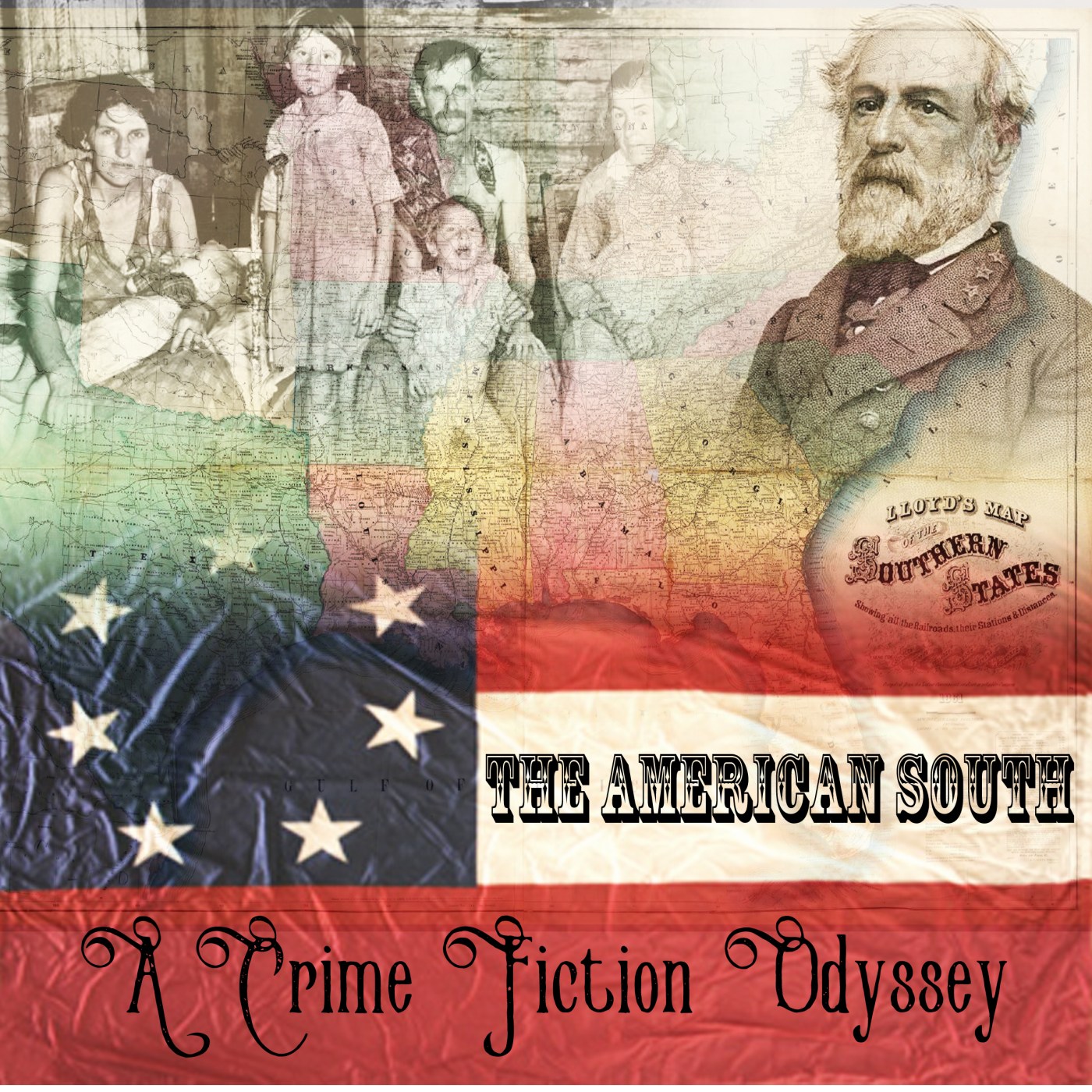

n opening word or three about the taxonomy of some of the crime fiction genres I am investigating in these features. Noir has an urban and cinematic origin – shadows, stark contrasts, neon lights blinking above shadowy streets and, in people terms, the darker reaches of the human psyche. Authors and film makers have always believed that grim thoughts, words and deeds can also lurk beneath quaint thatched roofs, so we then have Rural Noir, but this must exclude the kind of cruelty carried out by a couple of bad apples amid a generally benign village atmosphere. So, no Cosy Crime, even if it is set in the Southern states, such as Peaches and Scream, one of the Georgia Peach mysteries by Susan Furlong, or any of the Lowcountry novels of Susan M Boyer. Gothic – or the slightly tongue-in-cheek Gothick – will take us into the realms of the fantastical, the grotesque, and give us people, places and events which are just short of parody. So we can have Southern Noir and Southern Gothic, but while they may overlap in places, there are important differences.

n opening word or three about the taxonomy of some of the crime fiction genres I am investigating in these features. Noir has an urban and cinematic origin – shadows, stark contrasts, neon lights blinking above shadowy streets and, in people terms, the darker reaches of the human psyche. Authors and film makers have always believed that grim thoughts, words and deeds can also lurk beneath quaint thatched roofs, so we then have Rural Noir, but this must exclude the kind of cruelty carried out by a couple of bad apples amid a generally benign village atmosphere. So, no Cosy Crime, even if it is set in the Southern states, such as Peaches and Scream, one of the Georgia Peach mysteries by Susan Furlong, or any of the Lowcountry novels of Susan M Boyer. Gothic – or the slightly tongue-in-cheek Gothick – will take us into the realms of the fantastical, the grotesque, and give us people, places and events which are just short of parody. So we can have Southern Noir and Southern Gothic, but while they may overlap in places, there are important differences.

I believe there are just two main tropes in Southern Noir and they are closely related psychologically as they both spring from the same historical source, the war between the states 1861 – 1865, and the seemingly endless fallout from those bitter four years. Despite having a common parent the two tropes are, literally, of different colours. The first is set very firmly in the white community, where the novelists find deprivation, a deeply tribal conservativism, and a malicious insularity which has given rise to a whole redneck sub-genre in music, books and film, with its implications of inbreeding, stupidity and a propensity for violence.

eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or

eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or  thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant A Land More Kind Than Home (2013).

thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant A Land More Kind Than Home (2013).

No-one did sadistic and malevolent ‘white trash’ better than Jim Thompson. His embittered, cunning and depraved small town Texas lawman Lou Ford in The Killer Inside Me (1952) is one of the scariest characters in crime fiction, although it must be said that Thompson’s bad men – and women – were not geographically confined to the South.

lthough not classed as a crime writer, Flannery O’Connor write scorching stories about the kind of moral vacuum into which she felt Southern people were sucked. She said, well aware of the kind of lurid voyeurism with which her home state of Georgia was viewed by some:

lthough not classed as a crime writer, Flannery O’Connor write scorching stories about the kind of moral vacuum into which she felt Southern people were sucked. She said, well aware of the kind of lurid voyeurism with which her home state of Georgia was viewed by some:

“Anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic.”

Her best known novel, Wiseblood (1952) contains enough bizarre, horrifying and eccentric elements to qualify as Gothick. Take a religiously obsessed war veteran, a profane eighteen-year-old zookeeper, prostitutes, a man in a gorilla costume stabbed to death with an umbrella, and a corpse being lovingly looked after by his former landlady, you have what has been described as a work of “low comedy and high seriousness”

Her best known novel, Wiseblood (1952) contains enough bizarre, horrifying and eccentric elements to qualify as Gothick. Take a religiously obsessed war veteran, a profane eighteen-year-old zookeeper, prostitutes, a man in a gorilla costume stabbed to death with an umbrella, and a corpse being lovingly looked after by his former landlady, you have what has been described as a work of “low comedy and high seriousness”

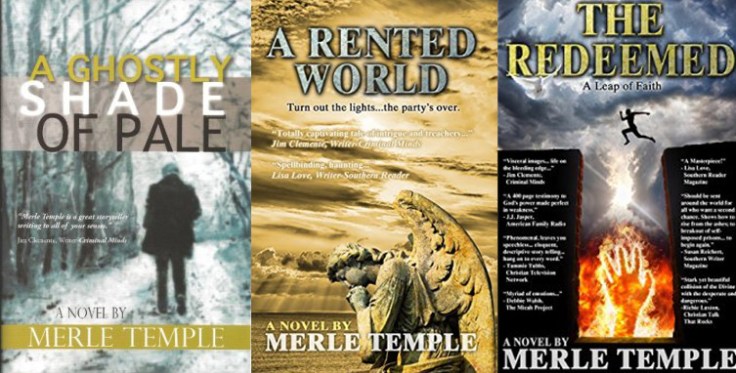

There are a couple of rather individual oddities on the Fully Booked website, both slanted towards True Crime, but drenched through with Southern sweat, violence and the peculiar horrors of the US prison system. The apparently autobiographical stories by Roy Harper were apparently smuggled out of the notorious Parchman Farm and into the hands of an eager publisher. Make of that what you will, but the books are compellingly lurid. Merle Temple’s trilogy featuring the rise and fall of Michael Parker, a Georgia law enforcement officer, comprises A Ghostly Shade of Pale, A Rented World and The Redeemed. I only found out after reading and reviewing the books that they too are personal accounts.

The second – and more complex (and controversial) trope in Southern Noir is the tortuous relationship between white people both good and bad, and people of colour. My examination of this will follow soon.

t is starkly obvious to anyone with even a passing knowledge of international history that the most brutal and bitterly fought wars tend to be between factions that have, at least in the eyes of someone looking in from the outside, much in common. No such war anywhere has cast such a long shadow as the American Civil War. That enduring shadow is long, and it is wide. In its breadth it encompasses politics, music, literature, intellectual thought, film and – the purpose of this feature – crime fiction.

t is starkly obvious to anyone with even a passing knowledge of international history that the most brutal and bitterly fought wars tend to be between factions that have, at least in the eyes of someone looking in from the outside, much in common. No such war anywhere has cast such a long shadow as the American Civil War. That enduring shadow is long, and it is wide. In its breadth it encompasses politics, music, literature, intellectual thought, film and – the purpose of this feature – crime fiction. There have been many commentators, critics and writers who have explored the US North-South divide in more depth and with greater erudition than I am able to bring to the table, but I only seek to share personal experience and views. One of my sons lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is a very modern city. In the 20th century it was a bustling hive of the cotton milling industry, but as the century wore on it declined in importance. Its revival is due to the fact that at some point in the last thirty years, someone realised that the rents were cheap, transport was good, and that it would be a great place to become a regional centre of the banking and finance industry. Now, the skyscrapers twinkle at night with their implicit message that money is good and life is easy.

There have been many commentators, critics and writers who have explored the US North-South divide in more depth and with greater erudition than I am able to bring to the table, but I only seek to share personal experience and views. One of my sons lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is a very modern city. In the 20th century it was a bustling hive of the cotton milling industry, but as the century wore on it declined in importance. Its revival is due to the fact that at some point in the last thirty years, someone realised that the rents were cheap, transport was good, and that it would be a great place to become a regional centre of the banking and finance industry. Now, the skyscrapers twinkle at night with their implicit message that money is good and life is easy. rive out of Charlotte a few miles and you can visit beautifully preserved plantation houses. Some have the imposing classical facades of Gone With The Wind fame, but others, while substantial and sturdy, are more modest. What they have in common today is that your tour guide will, most likely, be an earnest and eloquent young post-grad woman who will be dismissive about the white folk who lived in the big house, but will have much to say the black folk who suffered under the tyranny of the master and mistress.

rive out of Charlotte a few miles and you can visit beautifully preserved plantation houses. Some have the imposing classical facades of Gone With The Wind fame, but others, while substantial and sturdy, are more modest. What they have in common today is that your tour guide will, most likely, be an earnest and eloquent young post-grad woman who will be dismissive about the white folk who lived in the big house, but will have much to say the black folk who suffered under the tyranny of the master and mistress.

By contrast, a day’s drive south will find you in Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston is energetically preserved in architectural aspic, and if you are seeking people to share penance with you for the misdeeds of the Confederate States, you may struggle. In contrast to the spacious and well-funded Levine Museum in Charlotte, one of Charleston’s big draws is The Confederate Museum. Housed in an elevated brick copy of a Greek temple, it is administered by the Charleston Chapter of The United Daughters of The Confederacy. Pay your entrance fee and you will shuffle past a series of displays that would be the despair of any thoroughly modern museum curator. You definitely mustn’t touch anything, there are no flashing lights, dioramas, or interactive immersions into The Slave Experience. What you do have is a fascinating and random collection of documents, uniforms, weapons and portraits of extravagantly moustached soldiers, all proudly wearing the grey or butternut of the Confederate armies. The ladies who take your dollars for admission all look as if they have just returned from taking tea with Robert E Lee and his family.

By contrast, a day’s drive south will find you in Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston is energetically preserved in architectural aspic, and if you are seeking people to share penance with you for the misdeeds of the Confederate States, you may struggle. In contrast to the spacious and well-funded Levine Museum in Charlotte, one of Charleston’s big draws is The Confederate Museum. Housed in an elevated brick copy of a Greek temple, it is administered by the Charleston Chapter of The United Daughters of The Confederacy. Pay your entrance fee and you will shuffle past a series of displays that would be the despair of any thoroughly modern museum curator. You definitely mustn’t touch anything, there are no flashing lights, dioramas, or interactive immersions into The Slave Experience. What you do have is a fascinating and random collection of documents, uniforms, weapons and portraits of extravagantly moustached soldiers, all proudly wearing the grey or butternut of the Confederate armies. The ladies who take your dollars for admission all look as if they have just returned from taking tea with Robert E Lee and his family. Six hundred words in and what, I can hear you say, has this to do with crime fiction? In part two, I will look at crime writing – in particular the work of James Lee Burke and Greg Iles (but with many other references) – and how it deals with the very real and present physical, political and social peculiarities of the South. A memorable quote to round off this introduction is taken from William Faulkner’s Intruders In The Dust (1948). He refers to what became known as The High Point of The Confederacy – that moment on the third and fateful day of the Battle of Gettysburg, when Lee had victory within his grasp.

Six hundred words in and what, I can hear you say, has this to do with crime fiction? In part two, I will look at crime writing – in particular the work of James Lee Burke and Greg Iles (but with many other references) – and how it deals with the very real and present physical, political and social peculiarities of the South. A memorable quote to round off this introduction is taken from William Faulkner’s Intruders In The Dust (1948). He refers to what became known as The High Point of The Confederacy – that moment on the third and fateful day of the Battle of Gettysburg, when Lee had victory within his grasp.

Then there was the female comic, in the 1960s often from the north of England, like Hylda Baker. In fact, I’ve made my version – Jessie O’Mara – younger and more overtly feminist than Baker. The feminist movement was stirring in the 1960s. I’ve made O’Mara a Liverpool lass with a strong line in scouse chat.

Then there was the female comic, in the 1960s often from the north of England, like Hylda Baker. In fact, I’ve made my version – Jessie O’Mara – younger and more overtly feminist than Baker. The feminist movement was stirring in the 1960s. I’ve made O’Mara a Liverpool lass with a strong line in scouse chat.

A special kind of comic in the days of variety theatre was the ventriloquist. The most famous was Peter Brough whose dummy was Archie Andrews. The pair featured in a long-running radio show. (I could never see the point of doing a vent act any more than a juggling act on the radio.) So I’ve created Teddy Hooper and his dummy Percival Plonker who do what used to be called a cross-talk act of quick-fire gags.

A special kind of comic in the days of variety theatre was the ventriloquist. The most famous was Peter Brough whose dummy was Archie Andrews. The pair featured in a long-running radio show. (I could never see the point of doing a vent act any more than a juggling act on the radio.) So I’ve created Teddy Hooper and his dummy Percival Plonker who do what used to be called a cross-talk act of quick-fire gags.