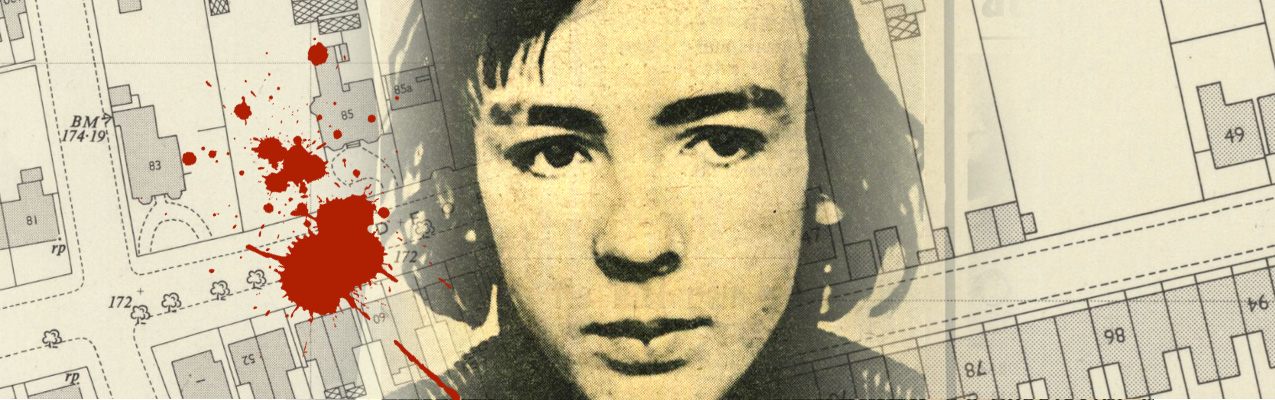

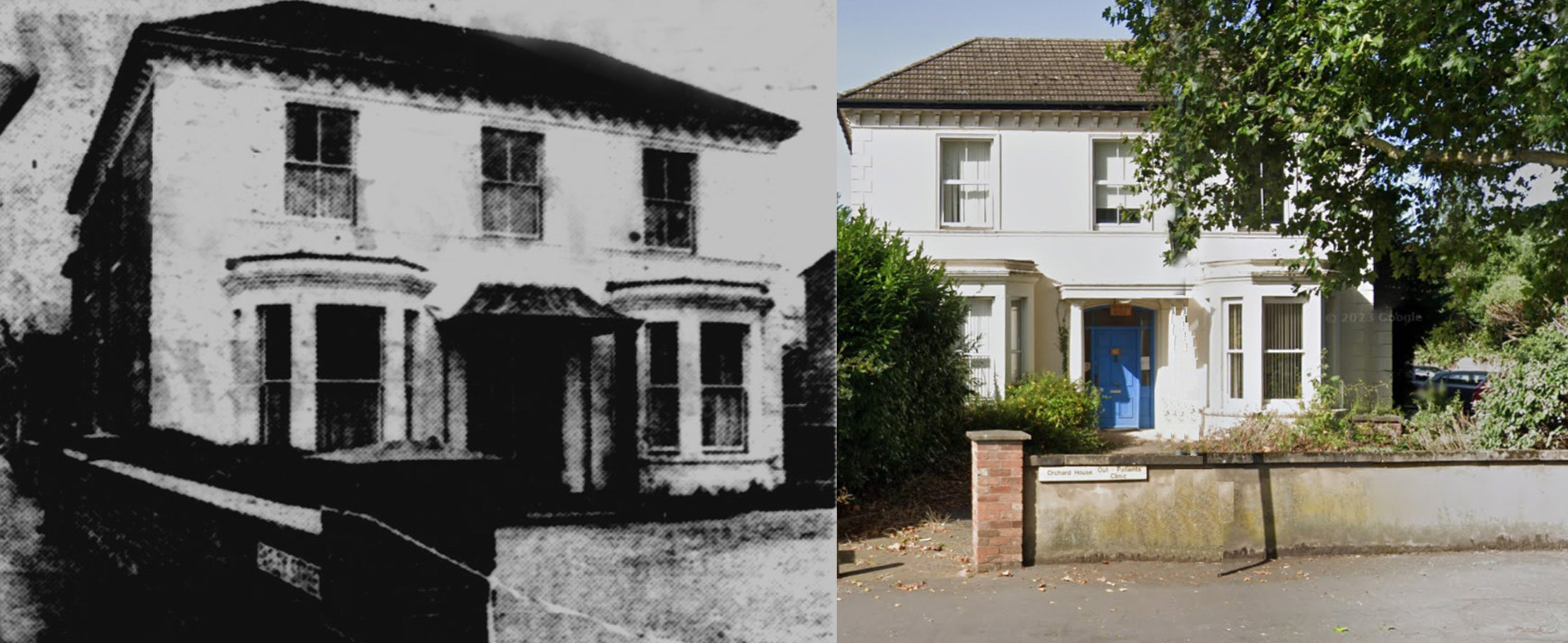

In the early hours of 2nd February 1976, an act of almost inhuman barbarity occurred in a rather grand Regency house on Radford Road, Leamington Spa. The house, number 83, was used as an annexe providing accommodation for nurses who worked at the nearby Warneford hospital. One such was 23 year old Tze Yung Tong. What were the circumstances that led her to be in Leamington? Misjudgment, or an act of cruelty by Fate?

Thomas Hardy ends what is, for me, his most powerful tragedy by commenting on the death by hanging of his heroine, Tess Durbeyfield. He says, “’Justice’ was done, and the President of the Immortals (in Aeschylean phrase) had ended his sport with Tess.” He refers to the Greek dramatist who imagined humans as mere playthings of the Gods, moved around like chess pieces for their entertainment. If you accept this concept is valid, then the Gods certainly played a very cruel trick on Tze Yung Tong.

It could be said that misfortune had played a part in putting the young Chinese woman in that particular place at that particular time. Trained as a nurse, she had married a travel courier in Hong Kong in 1973, and the couple had moved to Taiwan. The marriage did not last, however, and Tze, pregnant, moved back to her parents’ house in Hong Kong. When her son, Yat Chung Lam, was born, she made the fateful decision to move to England where the pay was much better, reasoning that she could send sufficient money home to better provide for the boy’s upbringing. The picture below shows Tze with her son in happier times.

On the morning of 2nd February Tze’s body was found in her room. The subsequent autopsy found that she had been stabbed multiple times in what must have been a frenzied assault. She had also been raped. At the murderer’s trial, the prosecution barrister told the jury:

“Two police officers came and were greeted with a horrible sight. Blood was everywhere, even splattered on the walls. Among evidence found by detectives were footprints on the roof leading to the landing window, and fingerprints on the landing windowsill, and on the outside of nurse Tong’s door. The pathologist examined the ghastly scene. Firstly there was a superficial cut on the nurse’s neck and it is considered the deceased was held at knife-point prior to her throat being cut. Also her clothes had been taken off after her throat had been cut. The pathologist also found she had laying on the bed completely passively in part because of loss of blood and partly through fear.”

Below – the house where Tze was murdered, as pictured in a 1976 newspaper and how it is today.

In researching these murder stories, I often wonder about the metaphor of a random rolling of the dice that puts two people on a collision course. More often than not, murders are committed by someone known to the victim, often a family member, but was this the case here? It also proved to be a case where the police, despite a huge allocation of manpower and resources, literally had no clue as to the identity of Tze’s killer, and it was only a loss of nerve on his part that resulted in his arrest and trial.Tze had finished her shift at the Warneford at around 9.00pm on 1st February and had walked back along the snow covered pavement to the nurses’ hostel. Again, fate intervened. The girls had been warned repeatedly to make sure their room doors were locked before they went to bed. Tze’s keys were found hanging on a hook on the side of her wardrobe.

Tze’s ravaged body was eventually released to her family, in this case her mother Kit Yu Chen who had flown in from Hong Kong, and one of her sisters – Patricia Tze Min Fung – who had travelled from Canada. Whatever secrets the girl’s remains held were consumed by the flames at Oakley Wood crematorium on 26th February. Her relatives did not stay for the funeral.

The police threw everything they had into the investigation but in a way, it was doomed from the start. There was no jealous boyfriend. Tze, with what might be called her ‘real life’ 6000 miles away in Hong Kong, was pleasant and polite, but had shown no desire to establish a social life in England. The Warneford was just somewhere where she could advance her midwifery skills before going home and use her qualifications to provide a better life for herself and her son. The police clutched at straws. Who was the well-spoken mystery man she had shared a meal with at a recent course in Stratford on Avon? Could local tailors shed any light on a pair of trousers found near the murder scene? Would the mass fingerprinting of thousands of Leamington men shed any light on the mystery?

Ironically, it was the latter scheme which would produce a result, but not in the way police imagined.

IN PART 2

A wedding

A honeymoon

A confession

September 2, 2024 at 4:27 pm

how come as it was such a gruesome the culprit only spent such a short time in prison as he got married few years later also how could someone marry him after he d done that surely he must have a conscience

LikeLike

September 2, 2024 at 8:54 pm

He married on 14th February 1976. His wife, Julie, was already carrying his child. What happened after that, I don’t know. He had been released by 1996, but whether Julie waited for him, there’s no way of knowing. As I said, he is most probably still out there somewhere. He would be in his late 60s now, so no age at all. Hanging had been abolished for over 10 years when he killed the nurse, and I imagine he was well aware of that. I hope he rots in hell.

LikeLike