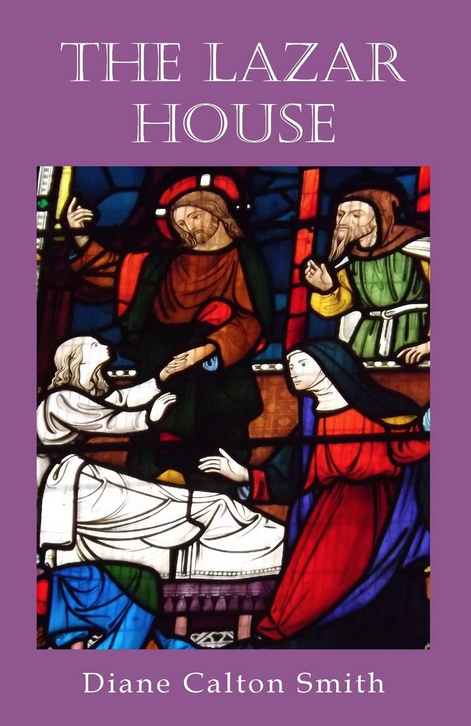

Diane Calton Smith’s medieval mysteries, set in Wisbech, don’t follow a continuous time line. The most recent, Back To The Flood, is set in 1249, while The Lazar House, published in 2022, is set in 1339. The geography of the town is much the same as in The Charter of Oswyth and Leoflede, where the author takes us back to 1190. In this book, most of the town still sits between two very different rivers. To the west, The Wysbeck is a sluggish trickle, easily forded, while to the east, the Well Stream is broader and more prone to violence.

South of the town is the hamlet of Elm (now a prosperous village) and on its soil stands The Lazar House. It is a hospice for those suffering from leprosy. Basically under the governance of the Bishop of Ely it must, however, be self financing. There was a deeply held belief, in those times, in the concepts of Heaven, Hell, and their buffer zone of purgatory. People believed that if they had any spare cash or – more likely – produce, and they gave it to a charity such as The Lazar House, then prayers would be said that would minimise the time donors’ souls had to spend waiting in the celestial ‘waiting room’ of Purgatory.

A rather grand supporter of The Lazar House is Lady Frideswide de Banlon. Widow of a rich knight, she has bestowed on The Lazar House tuns of fine ale from her demesne’s brewery, and it is a vital part of their constant attempts to stay solvent. Remember that ale, of various strengths, was a standard drink for all, as there was little water safe enough to drink.

Sadly, there is a downside. Frideswide is scornful, aggressive and deeply unpleasant in her dealings with those she deems lesser mortals. There is no shortage of people she has belittled, offended or denigrated. Much of the story unfolds through the eyes of Agathe, daughter of a local Reeve. She has chosen to work as what we now call a nurse at The Lazar House. Despite her robes, she has not taken Holy Orders and, should she choose, is perfectly able to accept the offer of marriage, proposed by another lay member of the community, Godwin the Pardoner. Put bluntly, his job is rather like that of a modern politician working with lobbyists. In return for financial favours or donations in kind, he has licence to forgive minor sins and guarantee that prayers of redemption will be whispered on a monthly, weekly – or daily basis – depending on the size of the donation.

When Lady Frideswide is found dead beside the footpath between The Lazar House and the brewery, the Bishop’s Seneschal, Sir John Bosse is sent for and he begins his investigation. His first conclusion is that Frideswide was poisoned, by deadly hemlock being added to flask of ale, found empty and discarded on the nearby river bank. He has the method. Now he must discover means and motive. Bosse is a shrewd investigator, and he realises that Frideswide was not, by nature, a charitable woman, therefore was the valuable gift of ale a penance for a previous sin? Pondering what her crime may have been, he rules out acts of violence, as they would have been dealt with by the authorities. Robbery? Hardly, as the de Banlon family are wealthy. He has what we would call a ‘light-bulb moment’, although that metaphor is hardly appropriate for the 14th century. Frideswide, despite her unpleasant manner, was still extremely beautiful, so Bosse settles for the Seventh Commandment. But with whom did she commit adultery?

When Lady Frideswide is found dead beside the footpath between The Lazar House and the brewery, the Bishop’s Seneschal, Sir John Bosse is sent for and he begins his investigation. His first conclusion is that Frideswide was poisoned, by deadly hemlock being added to flask of ale, found empty and discarded on the nearby river bank. He has the method. Now he must discover means and motive. Bosse is a shrewd investigator, and he realises that Frideswide was not, by nature, a charitable woman, therefore was the valuable gift of ale a penance for a previous sin? Pondering what her crime may have been, he rules out acts of violence, as they would have been dealt with by the authorities. Robbery? Hardly, as the de Banlon family are wealthy. He has what we would call a ‘light-bulb moment’, although that metaphor is hardly appropriate for the 14th century. Frideswide, despite her unpleasant manner, was still extremely beautiful, so Bosse settles for the Seventh Commandment. But with whom did she commit adultery?

When Bosse finds out the identity of her partner ‘between the sheets’, he is surprised, to say the least, but the revelation does not immediately bring him any nearer to finding her killer. The solution to the mystery, in terms of the plot, is very elegant, and worthy of one of the great writers of The Golden Age. It comes as a shock to the community, however, and brings heartbreak to more than one person. Diane Calton Smith draws us into the world of The Lazar House to the extent that when they suffer, so do we. The last few pages are not full of Hardy-esque bitterness and raging against life’s unfairness. Rather, they point more towards the sunlit uplands and, perhaps, better times ahead.

This is as clever a whodunnit as you could wish to read, and an evocative recreation of fourteenth century England. The author brings both the landscape and its people into vivid life. Published by New Generation Publishing The Lazar House is available now.

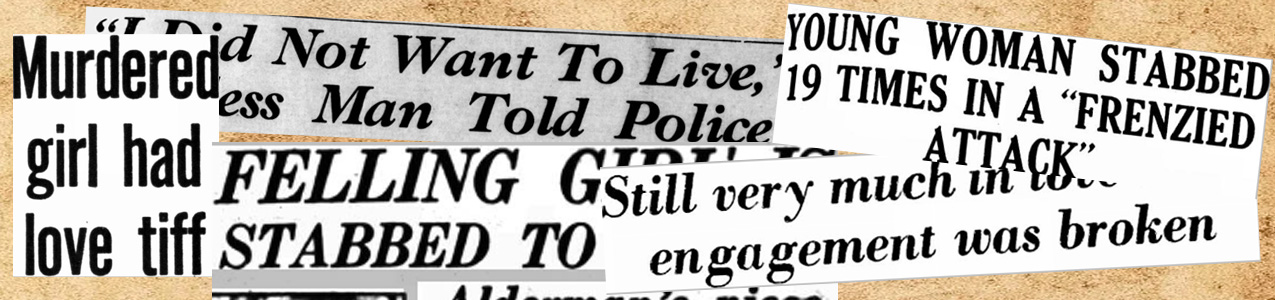

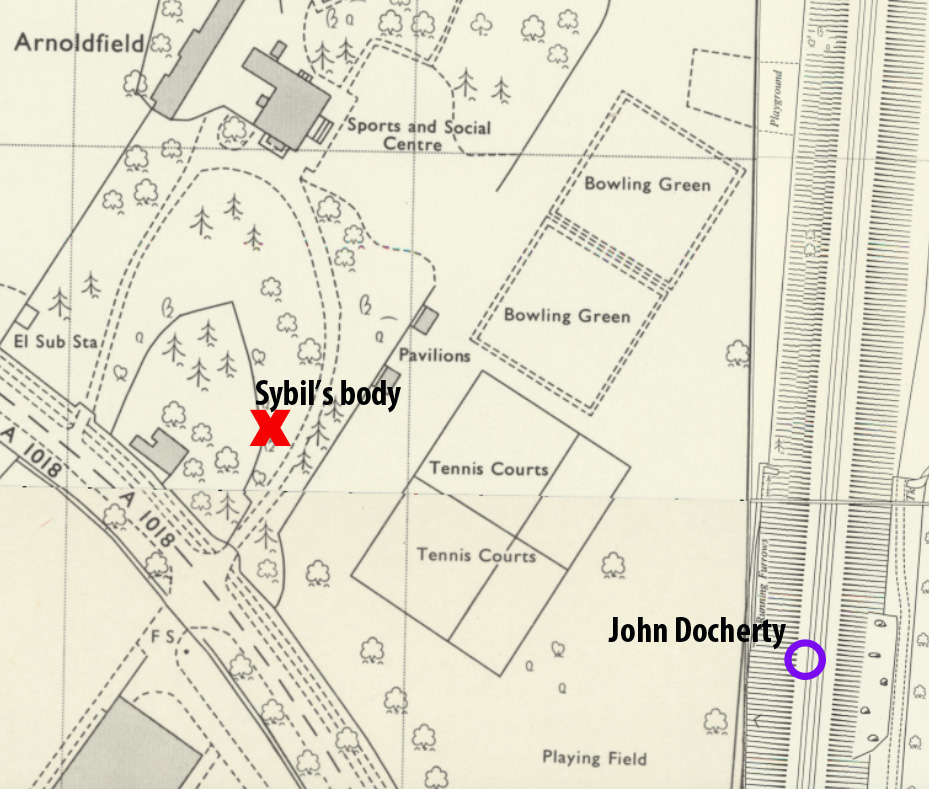

SO FAR: 10th August, 1954. Just after 11.00 am. In the drive leading up to the former mansion known as Arden Field just outside Grantham, the body of 24 year-old Sybil Hoy was found. She had been brutally murdered. Her body was taken away to the mortuary, and police began searching for the weapon. Just a few hundred yards away, across the Kings School playing fields, was the railway embankment that carried the London to Edinburgh main line. A railway lengthman (an employee responsible for walking a particular stretch of line checking for problems) had just climbed the embankments, and stood back as the London to Edinburgh service known as The Elizabethan Express thundered past.

SO FAR: 10th August, 1954. Just after 11.00 am. In the drive leading up to the former mansion known as Arden Field just outside Grantham, the body of 24 year-old Sybil Hoy was found. She had been brutally murdered. Her body was taken away to the mortuary, and police began searching for the weapon. Just a few hundred yards away, across the Kings School playing fields, was the railway embankment that carried the London to Edinburgh main line. A railway lengthman (an employee responsible for walking a particular stretch of line checking for problems) had just climbed the embankments, and stood back as the London to Edinburgh service known as The Elizabethan Express thundered past.

After her body had been probed and prodded by investigators, it was eventually returned to her mother and father. God, or whoever controls the heavens, was not best pleased, because a violent storm rained down on the many mourners at the Victorian Christ Church in Felling

After her body had been probed and prodded by investigators, it was eventually returned to her mother and father. God, or whoever controls the heavens, was not best pleased, because a violent storm rained down on the many mourners at the Victorian Christ Church in Felling

Sybil (right) was born in the summer of 1930, and grew up with her family in their house in the relatively comfortable Gateshead suburb of Felling. The few contemporary pictures which were published in newspapers at the time of her death show an attractive and confident young woman. At some point after WW2, she was courted by John Docherty, a few years her senior, who worked as a despatch clerk with a local firm. He was not in the best of health, and had been diagnosed with what Victorians called consumption. We now know it as tuberculosis and, despite reported occurrences of the disease within immigrant communities, it has now been conquered by immunisation. Docherty and Sybil became engaged, but at some point in the spring of 1954, Sybil had second thoughts, broke off the engagement and returned to Docherty the ring, and various other gifts.

Sybil (right) was born in the summer of 1930, and grew up with her family in their house in the relatively comfortable Gateshead suburb of Felling. The few contemporary pictures which were published in newspapers at the time of her death show an attractive and confident young woman. At some point after WW2, she was courted by John Docherty, a few years her senior, who worked as a despatch clerk with a local firm. He was not in the best of health, and had been diagnosed with what Victorians called consumption. We now know it as tuberculosis and, despite reported occurrences of the disease within immigrant communities, it has now been conquered by immunisation. Docherty and Sybil became engaged, but at some point in the spring of 1954, Sybil had second thoughts, broke off the engagement and returned to Docherty the ring, and various other gifts.

To use a cricketing term, the Dr Temperance Brennan book series by Kathy Reichs (left) is 24 not out, and still looking good. The series featuring the forensic anthropologist began with Déjà Dead in 1997. For anyone new to the novels, I’ll just direct you

To use a cricketing term, the Dr Temperance Brennan book series by Kathy Reichs (left) is 24 not out, and still looking good. The series featuring the forensic anthropologist began with Déjà Dead in 1997. For anyone new to the novels, I’ll just direct you