We haven’t had a resounding cad in popular fiction since George MacDonald Fraser took Harry Flashman, a relatively minor character in a little-read Victorian school novel, and had him bestride the 19th century like a colossus, meeting (and cheating) pretty much everyone from Abraham Lincoln to Otto von Bismarck. Now, Clive Woolliscroft introduces Lieutenant William Dunbar, an impoverished younger son of a Scottish nobleman – and utter bounder*.

* Bounder (noun, archaic): a man who behaves badly or in a way that is not moral, especially in his relationships with women.

Unlike Flashman, Dunbar doesn’t lack physical courage, and he fights with his regiment against Bonnie Prince Charlie’s highlanders at Culloden, so this places the events of the novel somewhere in the years after 1746. Dunbar, however, has neither the skills nor the family fortune to lead the rich man’s life he so desperately craves, and so he is on the look-out for wealth by marriage. Can he find a suitable young woman, with a sizeable *tocher and generous annual allowance from her wealthy parents?

* Tocher (Scots, archaic): A dowry: a marriage settlement given to the groom by the bride or her family.

For the first 120 pages or so, we view events through the eyes of William Dunbar. Thereafter, the narrative switches between that of Mercy Grundy and Dunbar. Quite early in the book, Dunbar had secretly married a Scottish heiress, Ann Macclesfield, (for her money of course) and she had borne him a daughter. The financial part of his plan had collapsed, due to religious complications after the battle of Culloden, but Anne now refuses to dissolve the marriage, thus putting a major impediment in the way of Dunbar’s plans to marry Mercy, and get his hands on her family’s wealth.

Dunbar leaves the army, and begins to make something of a living in the world of finance, managing to build up cash reserves, thus lessening the necessity of marriage. He then sees a chance to become very rich indeed by buying a share in a ship engaged in what was known, euphemistically, as the African Trade. This worked in a brutally simple fashion. The ship leaves Britain loaded with manufactured goods which could range from bolts of cloth to firearms and anything in between. These were then bartered for human cargo – slaves – on the coast of West Africa, which were then taken and sold in the slave markets of the Americas. In theory, the ship would then return to Britain, laden with cash.

Unfortunately for him, Dunbar’s ship, The Archer, is destroyed by fire after a mutiny of the slaves and he is, once again, left with nothing. He decides to try his luck once more with Mercy Grundy, but finding her father totally in opposition to his plans, he dupes Mercy into a course of action which will end disastrously for her. This mirrors the real life tragedy the book is based on – the case of Mary Blandy who, in 1752, was put on trial for poisoning her father.

The author served as an Army Officer in Germany, worked as an international money market trader in London, was a Management Consultant in Prague and Riga and practised as a solicitor in London, Hertfordshire, and Staffordshire. This is his second novel. ‘Less Dreadful With Every Step’ was published in May 2023.

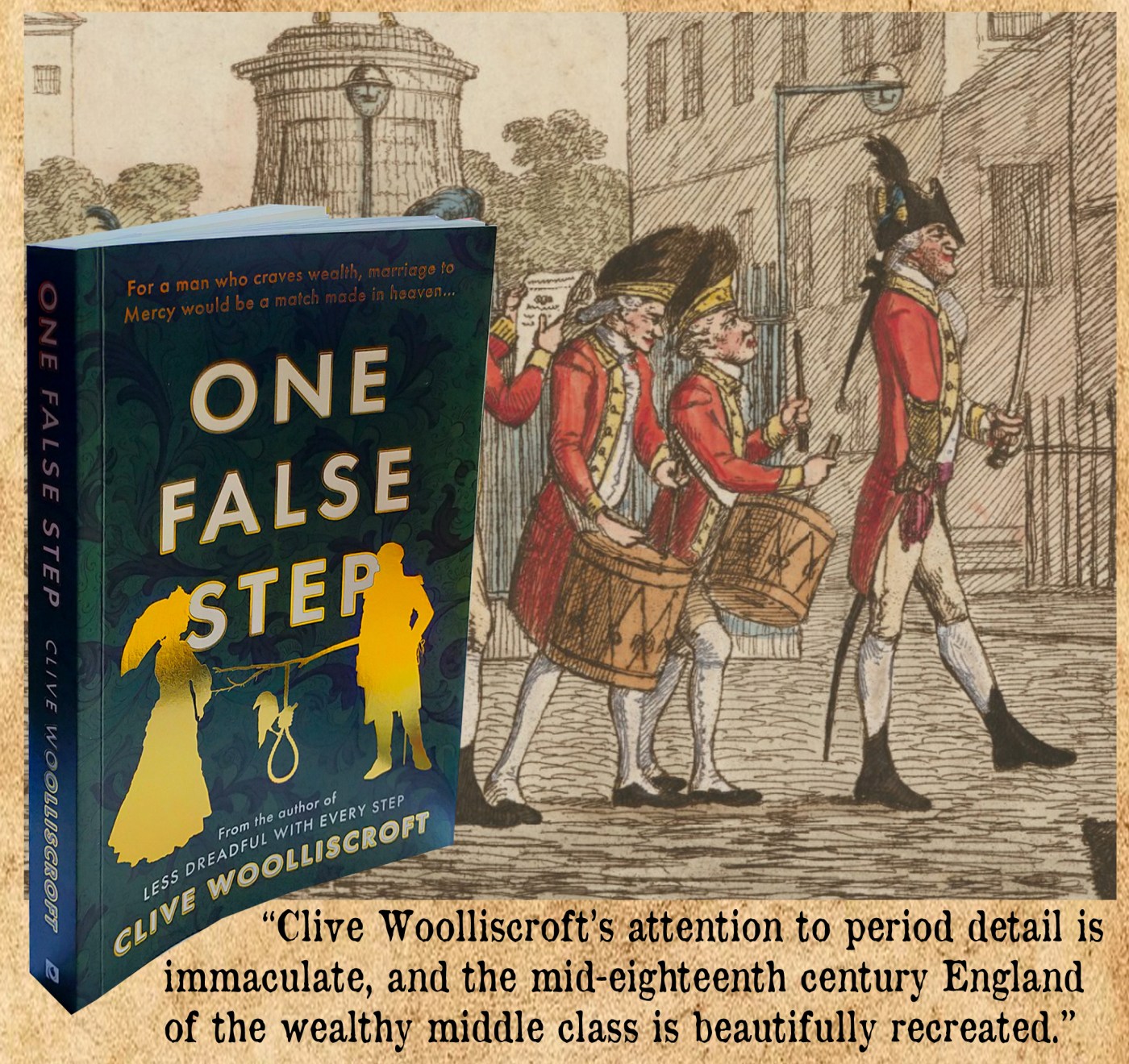

Clive Woolliscroft’s attention to period detail is immaculate, and the mid-eighteenth century England of the wealthy middle class is beautifully recreated. William Dunbar is an out and out villain, with none of the dubious charm possessed by Harry Flashman. The book’s title is extremely apposite for poor Mercy Grundy. One False Step is published by The Book Guild, and is available now.