Kate Webb introduced us to DI Matt Lockyer and DC Gemma Broad in Stay Buried, which I read, reviewed and found most impressive. Briefly, Lockyer is a single man, son of Wiltshire farmers – who would be described as ‘hard-scrabble’ in America. His younger brother, Chris, was murdered in a street brawl a few years earlier. He is involved – at a distance – with Hedy Lambert, a woman whose murder conviction he helped overturn. She still served over a decade in prison.

Because of a previous professional misjudgment, Lockyer has been sidelined into cold-case crimes. One such is the death of Holly Gilbert who fell – or was pushed – from a bridge into the path of a an HGV. Now, the remains one of the men suspected as having being involved, and who disappeared shortly after, have been discovered on Salisbury Plain. Lee Geary was a giant of a man, superficially very scary with his height, skinhead hair and tattoos, but he was simple in mind and spirit and his criminal convictions were all for minor and non violent crimes.

Three other twenty-somethings who were suspected of being involved in the death of Holly’s death have all since died in ambiguous circumstances. Lockyer has much on his mind. His mother lies dangerously ill in hospital, infected by a Covid variant, while his father struggles to keep the farm going. Lockyer lives in – and is slowly renovating – an old cottage, but he discovers that something horrific happened within its walls decades ago and, as is often the case, the past can often rear its ugly head to disrupt the relative tranquility of the present. I’ll give you a teaser – the book’s title is shared with another of the same name. If you take the trouble to Google, you will discover a rather delicate and elegant connection.

In trying to find out the truth about Lee Geary’s death, Lockyer is drawn, as if pulled by a magnet, to Old Hat Farm. It is owned by Vincent and Trish O’Neill, who lead something of an alternative life. They are are almost archetypal ‘hippies’, with lives organised around the ancient festivals such as Samhain and Beltain. Fellow seekers after truth are welcome at the farm but, unfortunately all of the key residents had lives in the real world, and it is their misdeeds in their previous lives which make up the puzzle Lockyer and Broad have to solve.

The novel is lovingly set in a part of England that the the author clearly knows well, and Lockyer’s intimate connection with the landscape – the vastness of Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire’s ancient sites and old trackways – brings a literary sense of place that was deployed so well by Thomas Hardy, but has been used by more recent writers in the crime genre such as Jim Kelly and Phil Rickson. As locals will know, the ravages caused by military training are brutal scars on the old fields and byways, but they are what they are.

Laying Out The Bones is not just a superior police procedural novel, but a powerful evocation of how historic lies and misjudgments can return to plague those involved. The empathy between Lockyer and Broad is utterly convincing, as is the awareness of what happened to us all during the Covid outbreak. The book’s plot is intricate, but beautifully fashioned, and although Matt Lockyer has something of a shock in the last page, I am sure he will survive to feature in a future episode of his career story. Published by Quercus, this book is available now.

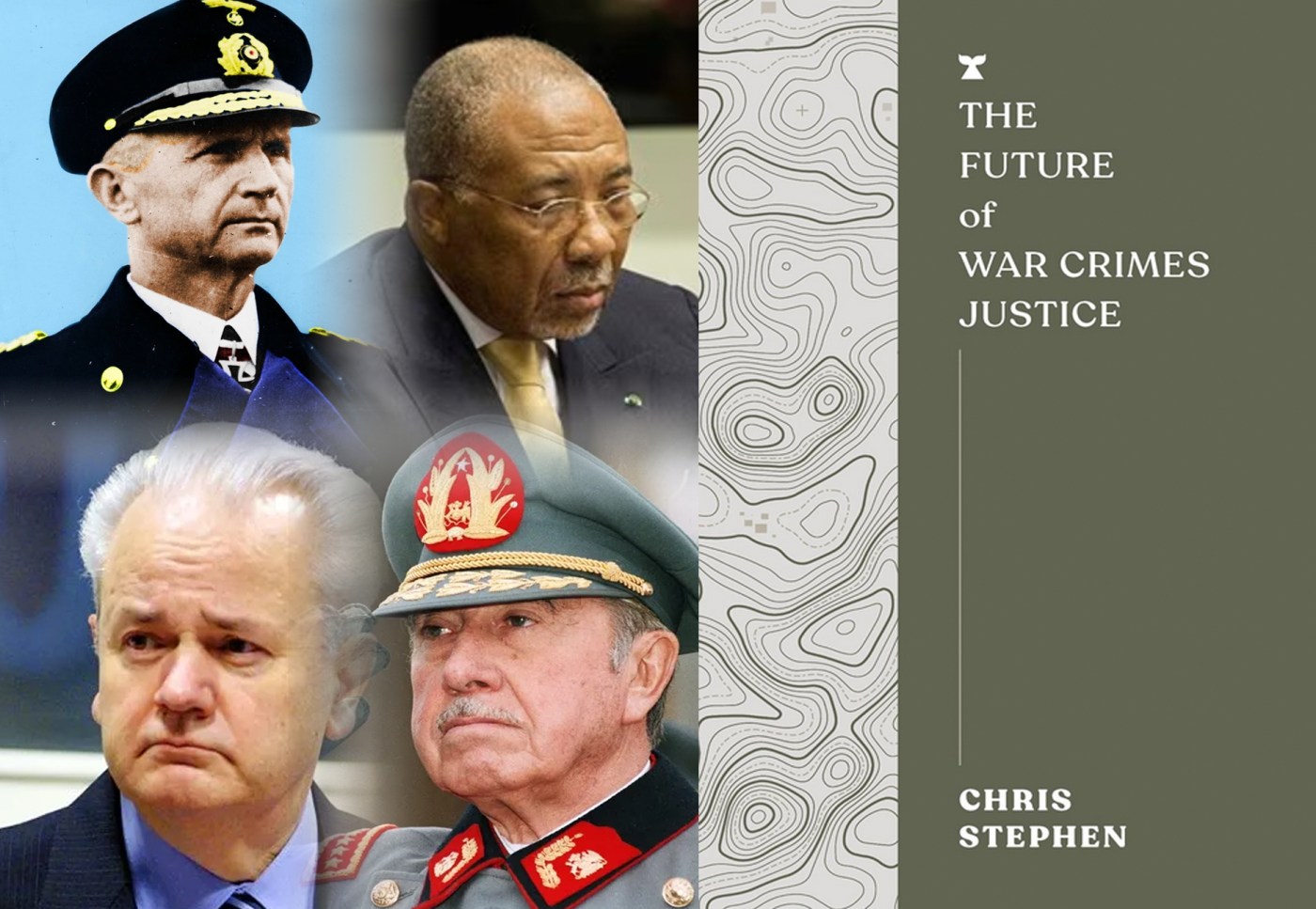

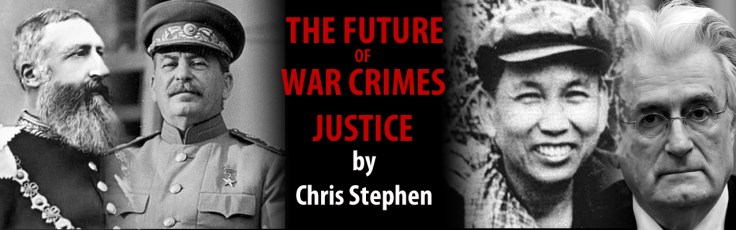

This is what used to be called a monograph, a slim volume devoted to one particular subject. It is a million miles away from Detective Inspectors, international criminals, sleepy villages with an abundance of elderly female amateur sleuths and dark deeds on the gloomy back-streets of Victorian London. However, I do try to balance my reading between novels and non-fiction, and this book repaid my interest. The author, journalist Chris Stephen (left) has reported from nine wars for publications including the Guardian and the New York Times magazine. He is the author of Judgement Day: The Trial of Slobodan Milošević (published by Atlantic Books). Ironically, the Serbian leader avoided becoming only the third former Head of State to be found guilty of war crimes, mainly because he died of a heart attack during his trial. The first was Admiral Karl Dönitz who, for a very brief spell. was leader of Nazi Germany. The second was Charles Taylor the former Liberian leader, at whose trial Naomi Campbell made a brief but bizarre appearance as a witness. This book is part of a new series from Melville House.

This is what used to be called a monograph, a slim volume devoted to one particular subject. It is a million miles away from Detective Inspectors, international criminals, sleepy villages with an abundance of elderly female amateur sleuths and dark deeds on the gloomy back-streets of Victorian London. However, I do try to balance my reading between novels and non-fiction, and this book repaid my interest. The author, journalist Chris Stephen (left) has reported from nine wars for publications including the Guardian and the New York Times magazine. He is the author of Judgement Day: The Trial of Slobodan Milošević (published by Atlantic Books). Ironically, the Serbian leader avoided becoming only the third former Head of State to be found guilty of war crimes, mainly because he died of a heart attack during his trial. The first was Admiral Karl Dönitz who, for a very brief spell. was leader of Nazi Germany. The second was Charles Taylor the former Liberian leader, at whose trial Naomi Campbell made a brief but bizarre appearance as a witness. This book is part of a new series from Melville House.