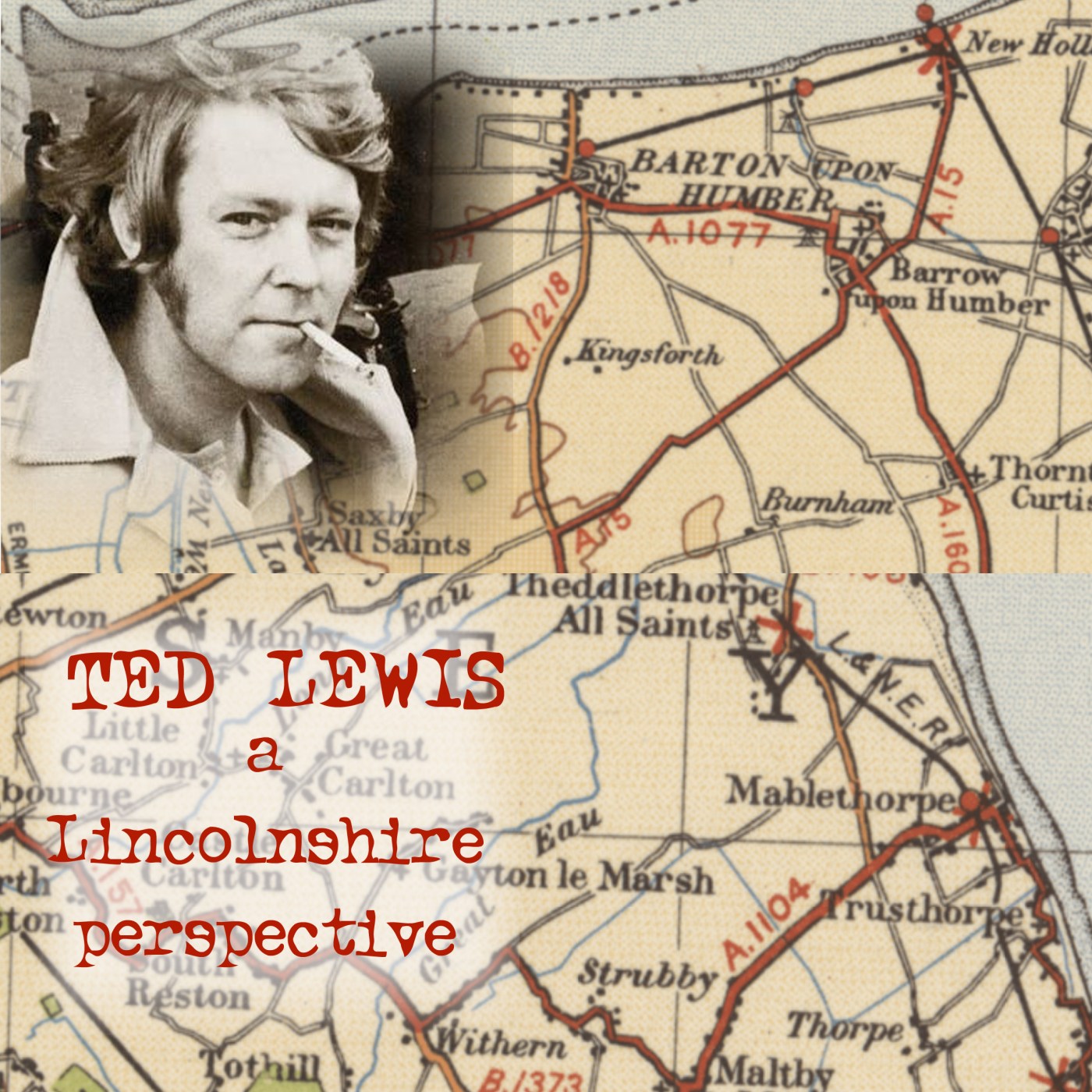

Alfred Edward Lewis was born in Stretford, Manchester on 15th January 1940, but in 1946 the family moved to Barton upon Humber. Five years later, Lewis passed his 11+ and began attending the town’s grammar school. There, he was fortunate enough to come under the influence of an English teacher called Henry Treece. Treece was born in Staffordshire, but had moved to Lincolnshire in 1939, and although he ‘did his bit’ as an RAF intelligence officer, he was able to make his name during the war years as a poet.

Alfred Edward Lewis was born in Stretford, Manchester on 15th January 1940, but in 1946 the family moved to Barton upon Humber. Five years later, Lewis passed his 11+ and began attending the town’s grammar school. There, he was fortunate enough to come under the influence of an English teacher called Henry Treece. Treece was born in Staffordshire, but had moved to Lincolnshire in 1939, and although he ‘did his bit’ as an RAF intelligence officer, he was able to make his name during the war years as a poet.

Ted Lewis excelled at both Art and English, and when it came to leaving school, he was desperate to go to Art School in Hull (now the Hull School of Art and Design). His parents thought this idea frivolous and a waste of time, and were determined that he should get ‘a proper job’ locally. Henry Treece interceded on Lewis’s behalf and was able to persuade his parents to let the young man cross the murky waters of the Humber to study.

After leaving the college, it seemed that Lewis was going to make his way as an artist and illustrator, and a book written by Alan Delgado, variously called The Hot Water Bottle Mystery or The Very Hot Water Bottle, can be had these days for not very much money, and the description on seller sites usually adds “Illustrated by Edward Lewis”. That was the first serious money Ted ever made. He moved to London in the early 1960s to further his prospects.

After leaving the college, it seemed that Lewis was going to make his way as an artist and illustrator, and a book written by Alan Delgado, variously called The Hot Water Bottle Mystery or The Very Hot Water Bottle, can be had these days for not very much money, and the description on seller sites usually adds “Illustrated by Edward Lewis”. That was the first serious money Ted ever made. He moved to London in the early 1960s to further his prospects.

His first published novel was All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965) and it is a semi-autobiographical account of the lives and loves of art students in Hull. I remember borrowing it from the local library not long after it came out and, looking back, it was a far cry from the novels that would make Lewis’s fame and fortune.

His first published novel was All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965) and it is a semi-autobiographical account of the lives and loves of art students in Hull. I remember borrowing it from the local library not long after it came out and, looking back, it was a far cry from the novels that would make Lewis’s fame and fortune.

Five years later, Lewis was getting regular script work in television, but now his second novel was published. Its original title was Jack’s Return Home. I believe that to be a reference to a mock Victorian melodrama of the same name, that featured in a Tony Hancock episode called The East Cheam Drama Festival. In Lewis’s book, the main character is Jack Carter, a London gangster returning to his home town to investigate the death of his brother. Re-badged as Get Carter, it was made into one of the finest British films ever made. It was released in March 1970, and Lewis is credited, along with director Mike Hodges, with the screenplay. Incidentally, a hardback first edition of JRH can be yours – a snip at just £3,250 (admittedly with a hand-written note by the author)

of the finest British films ever made. It was released in March 1970, and Lewis is credited, along with director Mike Hodges, with the screenplay. Incidentally, a hardback first edition of JRH can be yours – a snip at just £3,250 (admittedly with a hand-written note by the author)

Although the film is clearly set in Newcastle, the action in the book takes place in the far less glamorous setting of a ‘steel city’ much closer to where Lewis grew up – Scunthorpe, obviously. Sadly, the town was already regarded as a metaphor for somewhere awful, and the butt of many jokes, so setting Lewis’s story there would probably have been box office suicide.

Lewis wrote more novels, none achieving quite the success of Get Carter, although he returned to the character in his penultimate novel Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon (1977). By this time, however, Lewis was in a self induced spiral of decline, mainly due to alcohol abuse. His final novel, which many critics  believe to be his finest was GBH, published in 1980. Here, he unequivocally returns to Lincolnshire, and a bleak and down-beat out-of-season seaside town which is obviously Mablethorpe. The central character is George Fowler, a mobster who has made a living out of distributing porn movies, but has crossed the wrong people, and needs somewhere to hide up for a while. Rather like his creator, Fowler is in the darkest of dark places, and the novel ends in brutal and surreal fashion on a deserted Lincolnshire beach, with the wind howling in from the north sea as Fowler meets his maker in the remains of an RAF bombing target.

believe to be his finest was GBH, published in 1980. Here, he unequivocally returns to Lincolnshire, and a bleak and down-beat out-of-season seaside town which is obviously Mablethorpe. The central character is George Fowler, a mobster who has made a living out of distributing porn movies, but has crossed the wrong people, and needs somewhere to hide up for a while. Rather like his creator, Fowler is in the darkest of dark places, and the novel ends in brutal and surreal fashion on a deserted Lincolnshire beach, with the wind howling in from the north sea as Fowler meets his maker in the remains of an RAF bombing target.

With his marriage over and career in ruins, Lewis returned home to Barton, to live with his mother, but his health had gone, and the Grimsby Evening Telegraph ran this melancholy story on 30th March 1982. There is something deeply sad about a man who had the world at his feet, immensely gifted as a writer and artist, and a man whose literary legacy would prove to be immense, being taken by ambulance from a modest semi in Ferriby Road to a ward in Scunthorpe hospital, where he would die a few days later.

So what was the legacy of Ted Lewis? Some critics have dubbed him ‘England’s Albert Camus’. I don’t buy into that, for any number of reasons, one of which is that I have never knowingly been captivated by any book written by the French existentialist, while GBH, to name but one of Lewis’s books, gripped me by the throat and never let go until I had reached the final page. Another description of Lewis is that he was the ‘Godfather of English Noir.’ There isn’t time here to go into what is and isn’t ‘Noir’ in books and films, but let’s settle for a few descriptions, in no particular order: bleakly pessimistic; realistic; violent; deeply flawed characters; full of dark humour.

The more sharp-eyed of you will see that the cover of GBH bears the legend ‘with an afterword by Derek Raymond.’ Raymond (aka Robin Cook) was also self destructive, but he managed to survive until 1994, and left a catalogue of brutal, compassionate and disturbing crime novels, perhaps the best of which is I Was Dora Suarez. There is no evidence that Raymond was influenced by Lewis, but he clearly recognised a kindred spirit. But this article is about Lincolnshire. Lewis’s life – and his greatest novels – are book-ended by the county. He described the grimy and frequently corrupt world of a town dominated by a thriving steel industry (Scunthorpe) in Jacks’ Return Home and – when his personal life was in total disarray – he made his last words play out in GBH, resonating over the often bleak seashores around Mablethorpe, a place he must have visited with his parents when he was young. For George Fowler, however, there was not to be the long walk from the railway station to the beach; no arcades with penny slot machines, not a sniff of the intoxicating sweetness of candy floss, no jingling of bells from the donkey rides, and not a hint of the itchy reassurance of Mablethorpe sand between his toes. All that remained was an almost surreal death, which Lewis described brilliantly, while making sure we readers were never certain about what was real and what was not.

The good folk of Barton upon Humber have, perhaps rather belatedly, chosen to honour their two most famous literary sons. There is a Ted Lewis Centre, and his mentor from back in the day is acknowledged with a blue plaque. For a more detailed account of Ted Lewis’s life, I can recommend Getting Carter by Nick Triplow.

Leave a comment