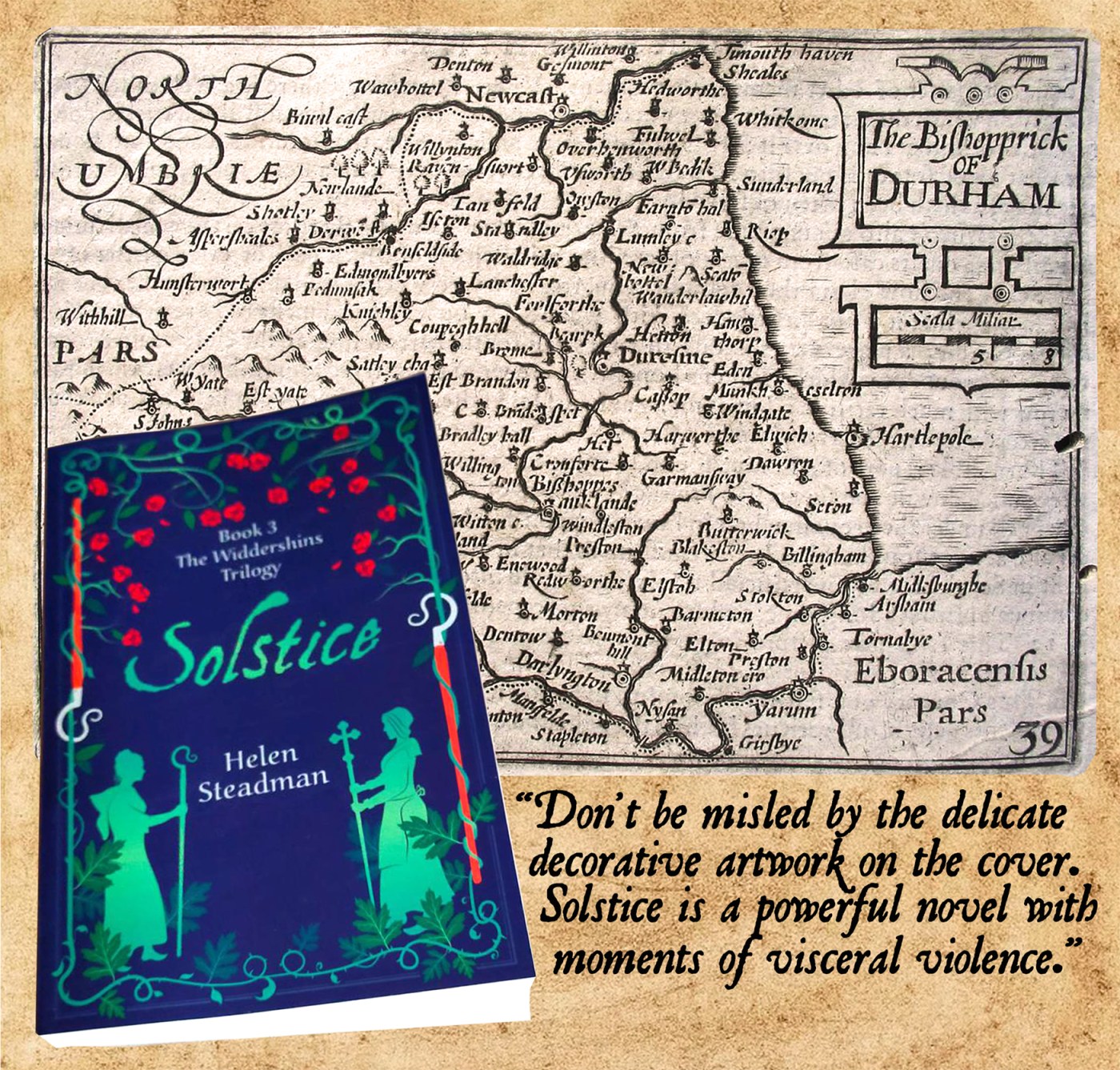

This is the final novel in the Widdershins trilogy, the previous two being Widdershins and Sunwise (both 2022). Most people with a smattering of historical knowledge will be aware of witch trials, perhaps most notably the events in Massachusetts in the late 17th century, famously dramatised by Arthur Miller in his play The Crucible. Closer to home, of course, were the events at Pendle in Lancashire much earlier in that century, and lovers of Hammer films (and Vincent Price) will be aware of the work of Matthew Hopkins – The Witchfinder General – in East Anglia during the English Civil War. I was totally unaware that there had been a virulent campaign against so-called witches in and around Newcastle in the 1670s. This is Helen Steadman’s subject.

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as ‘against the way’, as in going the opposite way to the sun, which was an important part of many pre-Christian religions. The story plays out in the unlikely-sounding hamlet of Mutton Clog, in County Durham, and Helen Steadman (left) has created two dramatically contrasting female central characters. Patience Leaton is the daughter of an Anglican minister, who has been forced to leave his benign and comfortable living in Ely due to the shame brought on the family by his wife’s very public infidelity. Earnest, Patience’s twin brother – due to serve with the Royal Navy – has reluctantly accompanied them. In the opposite corner, as it were, is Rose Driver, the beautiful and passionate daughter of a local farmer, Andrew Driver.

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as ‘against the way’, as in going the opposite way to the sun, which was an important part of many pre-Christian religions. The story plays out in the unlikely-sounding hamlet of Mutton Clog, in County Durham, and Helen Steadman (left) has created two dramatically contrasting female central characters. Patience Leaton is the daughter of an Anglican minister, who has been forced to leave his benign and comfortable living in Ely due to the shame brought on the family by his wife’s very public infidelity. Earnest, Patience’s twin brother – due to serve with the Royal Navy – has reluctantly accompanied them. In the opposite corner, as it were, is Rose Driver, the beautiful and passionate daughter of a local farmer, Andrew Driver.

The liberal ideas and laissez faire of the Restoration have clearly left Reverend Hector Leaton behind, as he is very Cromwellian in his distaste for anything resembling joy and pleasure, certainly where his church and its parishioners are concerned. Spurred on by the puritanical Patience, he is determined to put an end to any customs or celebrations in Mutton Clog that hint at England’s pagan past. He issues an interdict against any celebration of old customs like the equinox or the solstice, and there is a poignant passage where Rose sits on a black hill top and gazes around at the Beltane bonfires burning joyfully in distant villages.

In Mutton Clog, however, all is dark, both literally and metaphorically. Rose and Earnest have fallen in – if not love, then certainly lust – with each other, and when inevitable moment of passion is over Rose, ever in tune with her own body, senses that there will be dire consequences – a baby. Patience has been a scandalised witness of what took place, and informs her father. A hasty marriage is arranged, of which the only beneficiaries are Hector and Patience Leaton, and their sanctimony. As for Earnest, he is called to arms, and goes off to join his ship in the long running naval feud with the Dutch.

Rose is kept virtual prisoner in the Rectory, while the baby inside her grows. Very soon, however, comes news that Earnest’s ship has been sunk with all hands, and so she becomes Widow Leaton. Worse is to follow, as Patience tirelessly seeks to prove that Rose and her family are involved in witchcraft. She wants nothing more than to see Rose and her unborn child dead and buried, preferably not in the holy ground of Mutton Clog churchyard, and she uses the primitive criminal justice system of the day to sate her desire for justice against those who defile what she sees as ‘God’s Way’.

I can’t recall a more vindictive and unpleasant fictional female character than Patience Leaton, other than Trollope’s Mrs Proudie. The wife of the long suffering Bishop of Barchester had, however, several volumes in which to become more nuanced. Over 232 pages, Patience Leaton is simply vile. Her scheming does claim a life in the end, but not the one she was seeking.

Don’t be misled by the delicate decorative artwork on the cover. There is nothing twee about Solstice. It is a dark and disturbing read, with echoes of the kind of Aeschylean tragedy found in Thomas Hardy’s novels. Helen Steadman’s novel is a stark reminder of a more brutal time, when the English church was at the head of an army of bigoted zealots, determined to wage war on the simple and time-proven beliefs of ordinary people who were in tune with nature and the seasons. Solstice is published by Bell Jar Books and is available now.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it.

Brat Farrar is an ingenious invention. He is an orphan, and even his name is the result of administrative errors and poor spelling. He has been around the world trying to earn a living in such exotic locations as New Mexico, but has ended up in London, virtually penniless and becomes an easy mark for a chancer like Alec Loding. He is initially reluctant to take art in the scheme, but with Loding’s meticulous coaching – and his own uncanny resemblance to the late Patrick – he convinces the Ashbys that he is the real thing. But – and it is a very large ‘but’ – Brat senses that Simon Ashby has his doubts, and they soon reach a disturbing kind of equanimity. Each knows the truth about the other, but dare not say. The author’s solution to the conundrum is elegant, and the endgame is both gripping and has a sense of natural justice about it. Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

Josephine Tey was one of the pseudonyms of Elizabeth MacKintosh (1896-1952) Her play, Richard of Bordeaux (written as Gordon Daviot) was celebrated in its day, and was produced by – and starred – John Gielgud. She never married, but a dear friend – perhaps an early romantic attachment – was killed on the Somme in 1916. She remained an enigma – even to friends who thought themselves close – throughout her life. Her funeral was reported thus:

The song, which has many more verses, was written as a sarcastic response to a statement made – allegedly by the MP Nancy Astor – criticising the 8th Army for not being part of the D Day landings in June 1944. Historian and broadcaster James Holland (left) has written an account of the Italian Campaign from the invasion of the mainland in September 1943 until the year’s end and, having read it, I can only think that the bitterness of the 8th Army men was more than justified.

The song, which has many more verses, was written as a sarcastic response to a statement made – allegedly by the MP Nancy Astor – criticising the 8th Army for not being part of the D Day landings in June 1944. Historian and broadcaster James Holland (left) has written an account of the Italian Campaign from the invasion of the mainland in September 1943 until the year’s end and, having read it, I can only think that the bitterness of the 8th Army men was more than justified.