This begins very differently from any of the previous books in the excellent series. Instead of finding retired Lancashire copper Henry being barman and barrista in his moorland pub, or helping his one-time colleagues chase villains around the mean backstreets of Blackpool, we are in Cyprus, where Viktor Bakshim, head of an Albanian crime syndicate has his lair in a heavily guarded mansion. He has, naturally, a bodyguard of muscled young men in black T-shirts, but his security on the island is further enhanced by the Cypriot authorities’ determination (thanks to wads of used Euros) to “see no ships..”

Bakshim is old and frail, and his body is pretty much shutting down one function at a time, like shops on a run-down town centre. At the heart of his operation is his ruthless and resourceful daughter Sofia, and she looms large as the plot develops.

The problem for the wider authorities – including the CIA, FBI and MI6 – is that Bakshim is dead. At least, he is supposed to be. It seems, however, that a co-ordinated hit on the ageing villain was foiled by crafty switching of personnel between the Land Cruisers carrying him and his hoodlums. The DNA of all the deceased thugs has been established, except the most crucial one – Bakshim himself.

A shadowy operator called Flynn, a former colleague of Christie’s, who now has connections to official intelligence agencies, is on Cyprus trying to establish what Bakshim – if he is indeed still alive – is up to. After a chase and a shoot-out, Flynn manages to evade the protective heavies, and heads out to sea with his girlfriend. Meanwhile, also on the island, American agent Karl Donaldson, with a little help from his friends in London’s Metropolitan Police, has nabbed a Russian hitman called Sokolov – violent and brave, but none too bright – and wants to turn him for his own purposes.

Back in chilly England, Henry Christie is, once again, employed as a civilian consultant to his former employers, and is working with his new partner DS Debbie Blackstone on an historic – and grim – case of child sexual abuse. The case is harrowing, and there are no easy days, but at least there are no bullets flying. This all changes when the ultra-violent world of Albanian gangland comes to Lancashire. When the Bakshims visit a British criminal who has been working hand in hand with them, they find that their man in the UK has grown greedy, and is demanding a bigger slice of the cake. Bad move. All hell breaks loose.

Sofia has employed a violently competent hitman known as The Tradesman, a psychopath whose business front is running a crematorium for deceased pets. While Viktor and his daughter are spirited away from the carnage, The Tradesman goes on a murderous spree that leaves the Lancashire cops reeling and struggling to make sense of what is going on. Henry Christie gets caught up in the bloodbath, but remains physically unscathed. His heart (the metaphorical one) however, takes a severe hit as, yet again, his romantic illusions are shattered. This happens very publicly, and in a humiliating fashion, but the heartache doesn’t prevent him – almost accidentally – cracking the case wide open as he investigates an apparently trivial case of card fraud involving his pub.

In the aftermath, Flynn and Donaldson decide that the Bakshims have done enough damage, and are determined to act “off the books” and kill them. In a delicious twist, however – and I’ll stop there, because the ending is just too good for me to spoil things. Nick Oldham delivers the goods again with violence and mayhem sufficient to satisfy the most demanding reader, but – best of all – we have another outing for the most endearing of English fictional coppers. Henry Christie is frequently bowed, but never, ever broken. Transfusion is published by Severn House and is out now.

For more about Henry Christie and Nick Oldham,

click the author’s picture below.

So, what is so special about the Carter Family and their songs? AP Carter’s ‘day job’ at one time, was traveling salesman.and he was a voracious collector of the songs that he heard as he moved from town to town. He clearly had a very good ear for melody. The words were almost certainly written down, but the tunes would have been just carried in his head. The songs are from a broad spread of different traditions. Some – in the lyrics at least – are clearly versions of songs that would have come over from the British Isles centuries earlier, while others are clearly 19th century American hymns and religious songs. Regarding the British songs, there is little or no sign of the modal tonality that you hear in later transcriptions of such songs by people like Ralph Vaughan Williams and Cecil Sharp. The astonishing thing is that overwhelming majority of Carter Family songs are what musicians call ‘three chord tricks’. In other words their harmonic structure is Tonic, Sub-Dominant and Dominant. Chord-wise, that means, if we are in the key of C, they use C major, F major G major and G seven. I have listened to dozens and dozens of recordings, and it is quite remarkable that they never seem to use a minor chord. The songs are almost always played using guitar chords in the key of C. That is not to say that the songs are in the absolute key of C, as Maybelle would use a capo. as well as detuning her guitar by as much as three or four semitones.

So, what is so special about the Carter Family and their songs? AP Carter’s ‘day job’ at one time, was traveling salesman.and he was a voracious collector of the songs that he heard as he moved from town to town. He clearly had a very good ear for melody. The words were almost certainly written down, but the tunes would have been just carried in his head. The songs are from a broad spread of different traditions. Some – in the lyrics at least – are clearly versions of songs that would have come over from the British Isles centuries earlier, while others are clearly 19th century American hymns and religious songs. Regarding the British songs, there is little or no sign of the modal tonality that you hear in later transcriptions of such songs by people like Ralph Vaughan Williams and Cecil Sharp. The astonishing thing is that overwhelming majority of Carter Family songs are what musicians call ‘three chord tricks’. In other words their harmonic structure is Tonic, Sub-Dominant and Dominant. Chord-wise, that means, if we are in the key of C, they use C major, F major G major and G seven. I have listened to dozens and dozens of recordings, and it is quite remarkable that they never seem to use a minor chord. The songs are almost always played using guitar chords in the key of C. That is not to say that the songs are in the absolute key of C, as Maybelle would use a capo. as well as detuning her guitar by as much as three or four semitones. It is no exaggeration to say that Maybelle Carter was one of the great innovators of guitar music. In terms of what she achieved she is up there with the greats alongside Reinhardt, Hendrix, Clapton, Cooder and – in her own genre, players like Doc Watson and Chet Atkins. I am a guitarist myself, and have been playing for over fifty years. It’s a good job I never had to earn my living from it, but I consider myself a reasonable amateur player. What Maybelle Carter did sounds elementary on the records, but when one comes to try and copy the style it is very, very difficult. She had several different techniques, but her signature style was what is known as ‘The Carter Scratch’. She plays melody with her thumb on the lower guitar strings, while using her index finger to strum out a percussive rhythm of the higher strings. She occasionally uses a different finger picking style, picked up from black blues players, which is more akin to ragtime syncopation.

It is no exaggeration to say that Maybelle Carter was one of the great innovators of guitar music. In terms of what she achieved she is up there with the greats alongside Reinhardt, Hendrix, Clapton, Cooder and – in her own genre, players like Doc Watson and Chet Atkins. I am a guitarist myself, and have been playing for over fifty years. It’s a good job I never had to earn my living from it, but I consider myself a reasonable amateur player. What Maybelle Carter did sounds elementary on the records, but when one comes to try and copy the style it is very, very difficult. She had several different techniques, but her signature style was what is known as ‘The Carter Scratch’. She plays melody with her thumb on the lower guitar strings, while using her index finger to strum out a percussive rhythm of the higher strings. She occasionally uses a different finger picking style, picked up from black blues players, which is more akin to ragtime syncopation. Sarah’s autoharp is an important feature on all the recordings. It backs up the incessant rhythm of Maybelle’s guitar, but because its strings are tuned much higher, it cuts through in the treble frequencies and provides an important texture to the music. Crucially, though, when you listen to a Carter Family recording it is mostly Sarah’s voice you hear. It would be wrong to call it a thing of beauty. It has a hard edge, with an almost masculine timbre. There is never any vibrato, but intonation-wise it is spot on every time, right in the middle of the note. The lyrics she sings are almost always shorn of pretension or ambiguity. They speak of simple truths – love, life, death, hardship, betrayal, joy and sorrow. Her voice tells it like it is. There is no doubt, no nuance but instead, utter conviction and sincerity.

Sarah’s autoharp is an important feature on all the recordings. It backs up the incessant rhythm of Maybelle’s guitar, but because its strings are tuned much higher, it cuts through in the treble frequencies and provides an important texture to the music. Crucially, though, when you listen to a Carter Family recording it is mostly Sarah’s voice you hear. It would be wrong to call it a thing of beauty. It has a hard edge, with an almost masculine timbre. There is never any vibrato, but intonation-wise it is spot on every time, right in the middle of the note. The lyrics she sings are almost always shorn of pretension or ambiguity. They speak of simple truths – love, life, death, hardship, betrayal, joy and sorrow. Her voice tells it like it is. There is no doubt, no nuance but instead, utter conviction and sincerity.

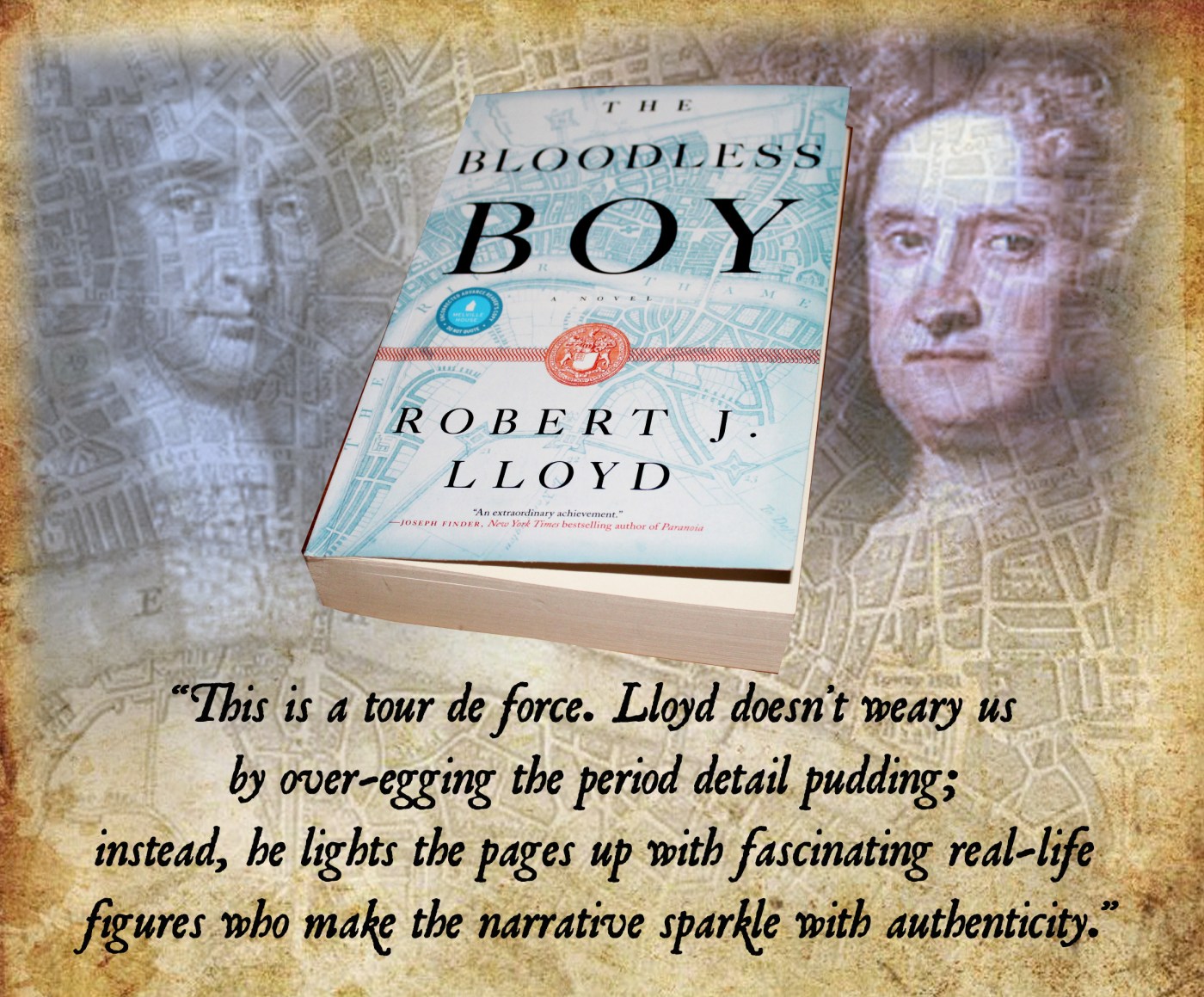

Thus begins a thoroughly intriguing murder mystery, steeped in the religious politics of the time. For over one hundred and fifty years, religion had defined politics. Henry VIII and his daughters had burned their ‘heretics’, and although the strife between Charles I and Parliament was mainly to do with authority and representation, many of Oliver Cromwell’s adherents were strident in their opposition to the ways of worship practiced by the Church if England. Now, Charles II is King. He is reputed to have sired many ‘royal bastards’ but none that could succeed to the throne, and the next in line, his brother James, has converted to Catholicism. In most of modern Britain the schism between Catholics and Protestants is just a memory, but we only have to look across the Irish Sea for evidence of the bitter passions that can still divide society.

Thus begins a thoroughly intriguing murder mystery, steeped in the religious politics of the time. For over one hundred and fifty years, religion had defined politics. Henry VIII and his daughters had burned their ‘heretics’, and although the strife between Charles I and Parliament was mainly to do with authority and representation, many of Oliver Cromwell’s adherents were strident in their opposition to the ways of worship practiced by the Church if England. Now, Charles II is King. He is reputed to have sired many ‘royal bastards’ but none that could succeed to the throne, and the next in line, his brother James, has converted to Catholicism. In most of modern Britain the schism between Catholics and Protestants is just a memory, but we only have to look across the Irish Sea for evidence of the bitter passions that can still divide society.

How on earth this superb novel spent many years floating around in the limbo of ‘independent publishing’ is beyond reason. While not quite in the ‘Decca rejects The Beatles‘ class of short sightedness, it is still baffling. The Bloodless Boy has everything – passion, enough gore to satisfy Vlad Drăculea, a sweeping sense of England’s history, a comprehensive understanding of 17th century science and a depiction of an English winter which will have you turning up the thermostat by a couple of notches. The characters – both real and fictional – are so vivid that they could be there in the room with you as you read the book.

How on earth this superb novel spent many years floating around in the limbo of ‘independent publishing’ is beyond reason. While not quite in the ‘Decca rejects The Beatles‘ class of short sightedness, it is still baffling. The Bloodless Boy has everything – passion, enough gore to satisfy Vlad Drăculea, a sweeping sense of England’s history, a comprehensive understanding of 17th century science and a depiction of an English winter which will have you turning up the thermostat by a couple of notches. The characters – both real and fictional – are so vivid that they could be there in the room with you as you read the book.

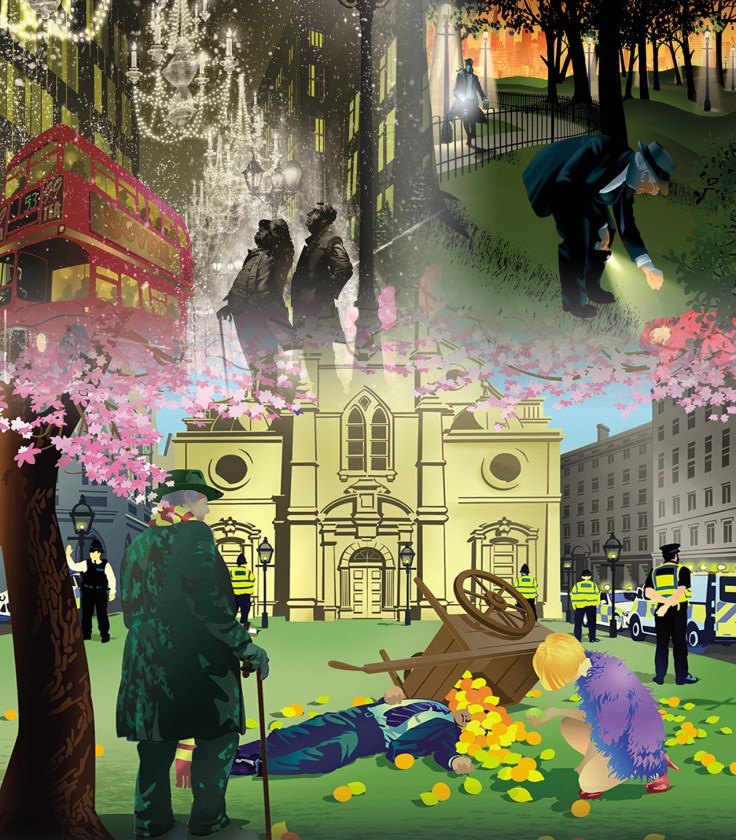

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

MJ is alive and well, and still writing, and Peter Maxwell appeared as recently as 2020 with Maxwell’s Summer. The series started in 1994 with Maxwell’s House, a title which (if you were around in the 1960s) will give you some idea of MJ’s wonderful sense of English domestic history – and his inability to resist a pun. The books are highly enjoyable, but never cosy. There is a streak of melancholy never far from the surface, and we are reminded that Maxwell’s first wife died when the car they were in was involved in a fatal collision. Max has never driven since, and his trusty bicycle is a regular prop in the stories. Max eventually marries his policewoman girlfriend Jackie Carpenter, which is only right and fair, since she is the plot device that has given him a very convenient ‘in’ with local murder investigations. MJ Trow has several other CriFi series to his name, and I list them below.

MJ is alive and well, and still writing, and Peter Maxwell appeared as recently as 2020 with Maxwell’s Summer. The series started in 1994 with Maxwell’s House, a title which (if you were around in the 1960s) will give you some idea of MJ’s wonderful sense of English domestic history – and his inability to resist a pun. The books are highly enjoyable, but never cosy. There is a streak of melancholy never far from the surface, and we are reminded that Maxwell’s first wife died when the car they were in was involved in a fatal collision. Max has never driven since, and his trusty bicycle is a regular prop in the stories. Max eventually marries his policewoman girlfriend Jackie Carpenter, which is only right and fair, since she is the plot device that has given him a very convenient ‘in’ with local murder investigations. MJ Trow has several other CriFi series to his name, and I list them below.

Inspector Lestrade – in which Trow ‘rehabilitates’ the much maligned copper in the Sherlock Holmes stories. 17 novels, beginning in 1985.

Inspector Lestrade – in which Trow ‘rehabilitates’ the much maligned copper in the Sherlock Holmes stories. 17 novels, beginning in 1985.

We are in Sicily, and it is the long hot summer of 1966. Brighton crime reporter Colin Crampton has taken his Aussie girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith abroad for a holiday. While the sun beats down, and gentle breezes blow in from the Mediterranean, Colin hopes to choose a romantic location – perhaps the ruin of a Greek temple – where he will go down on one knee and propose marriage to the beautiful Shirl. He has an expensive diamond ring in his pocket to help boost his case, but it is not to be.

We are in Sicily, and it is the long hot summer of 1966. Brighton crime reporter Colin Crampton has taken his Aussie girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith abroad for a holiday. While the sun beats down, and gentle breezes blow in from the Mediterranean, Colin hopes to choose a romantic location – perhaps the ruin of a Greek temple – where he will go down on one knee and propose marriage to the beautiful Shirl. He has an expensive diamond ring in his pocket to help boost his case, but it is not to be.

To Bath now, and a character created by (I think) Britain’s longest living (and still writing good books) crime author. Peter Lovesey was born in Middlesex in September 1936 and, after National Service and a career in teaching, he published his first novel in 1970. Wobble To Death was the first of a hugely successful series of historical novels featuring Sergeant Daniel Cribb and his assistant Constable Thackeray. Older readers will remember the superb BBC TV adaptations starring Alan Dobie (left) as Cribb. The stories were also dramatised by BBC radio.

To Bath now, and a character created by (I think) Britain’s longest living (and still writing good books) crime author. Peter Lovesey was born in Middlesex in September 1936 and, after National Service and a career in teaching, he published his first novel in 1970. Wobble To Death was the first of a hugely successful series of historical novels featuring Sergeant Daniel Cribb and his assistant Constable Thackeray. Older readers will remember the superb BBC TV adaptations starring Alan Dobie (left) as Cribb. The stories were also dramatised by BBC radio.

Zak Skinner is a pretty unremarkable guy in many ways. He’s bright enough, for sure – that’s why he is studying engineering at the University of Chicago. Why he moved there from NYU, we’re not sure at first, but we suspect that he lacks the essential ingredient of ‘stickability’. Or maybe he is running away from something? He and his old school buddy Riley room together, and Riley is most things that Zak is not. Like steady, reliable, unimaginative and not prone to destructive self analysis.

Zak Skinner is a pretty unremarkable guy in many ways. He’s bright enough, for sure – that’s why he is studying engineering at the University of Chicago. Why he moved there from NYU, we’re not sure at first, but we suspect that he lacks the essential ingredient of ‘stickability’. Or maybe he is running away from something? He and his old school buddy Riley room together, and Riley is most things that Zak is not. Like steady, reliable, unimaginative and not prone to destructive self analysis.