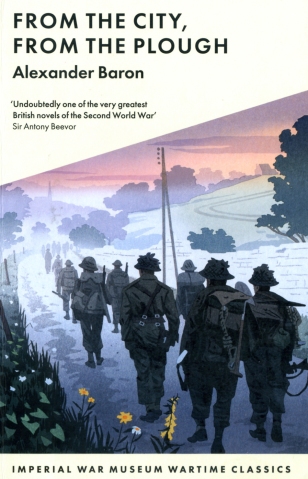

his 1948 best seller echoes Alexander Baron’s own military career as it follows a battalion of a fictional infantry brigade as they prepare for – and then take part in – D Day in the summer of 1944. The Fifth Wessex is, as the book’s title suggests, made up of a mixture of clumsy red-cheeked farm boys from the chalk uplands, well-read introverts who keep themselves to themselves, streetwise chancers and bewildered lads who are virgins in both bedroom and battlefield. They could be soldiers from earlier wars, and their ancestors might have known Agincourt, Marston Moor, Malplaquet, Talavera, Spion Kop and Arras. Baron has no time for the thinly veiled homo-eroticism of some of the Great War writers. His men can be uncouth, foul-mouthed, brutalised by their social background, yet given to moments of great compassion and charity.

his 1948 best seller echoes Alexander Baron’s own military career as it follows a battalion of a fictional infantry brigade as they prepare for – and then take part in – D Day in the summer of 1944. The Fifth Wessex is, as the book’s title suggests, made up of a mixture of clumsy red-cheeked farm boys from the chalk uplands, well-read introverts who keep themselves to themselves, streetwise chancers and bewildered lads who are virgins in both bedroom and battlefield. They could be soldiers from earlier wars, and their ancestors might have known Agincourt, Marston Moor, Malplaquet, Talavera, Spion Kop and Arras. Baron has no time for the thinly veiled homo-eroticism of some of the Great War writers. His men can be uncouth, foul-mouthed, brutalised by their social background, yet given to moments of great compassion and charity.

The British officer class have been long the object of scorn in both poetry and prose, but Baron deals with them in a largely sympathetic way. Those leading the Fifth on the ground are decent fellows; people who are only too aware of the frequently uneven struggle between shards of steel and the breasts of brave men. Even the Brigadier, whose plans prove so costly, is well aware of what he asks. He is, however, resolute in the way he shuts down his personal qualms in order to maintain the integrity of the battle plan. The one exception is the odious Major Maddison, a cold and sexually troubled narcissist whose demise is as satisfying as it is inevitable.

The British officer class have been long the object of scorn in both poetry and prose, but Baron deals with them in a largely sympathetic way. Those leading the Fifth on the ground are decent fellows; people who are only too aware of the frequently uneven struggle between shards of steel and the breasts of brave men. Even the Brigadier, whose plans prove so costly, is well aware of what he asks. He is, however, resolute in the way he shuts down his personal qualms in order to maintain the integrity of the battle plan. The one exception is the odious Major Maddison, a cold and sexually troubled narcissist whose demise is as satisfying as it is inevitable.

It is worth comparing From The City, From The Plough to another deeply moving novel of men at war, Covenant With Death, (1961) by John Harris. Both deal at length with preparation for an assault; both conclude with the devastating outcome. In Harris’s book the ‘band of brothers’ is a thinly fictionalised Pals Battalion from a northern city. Their Gehenna is the morning of July 1st 1916 and if it is just as brutal as the fate of the Fifth Wessex, it is perhaps more shocking for its suddenness. Harris concludes his book with the words;

“Two years in the making. Ten minutes in the destroying. That was our story.”

aron writes lyrically about the midsummer grace of the French countryside, its orchards and abundance of wild flowers, some of which grace the helmets and tunics of the passing soldiers, their fragility which will contrast cruelly with the total vulnerability of the crumpled and shattered bodies of the men who wore them. For the driven and exhausted men of the Fifth Wessex, unlike their fathers before them, there is always a new unspoiled hillside, a grove of trees untouched by shellfire, a fresh sunken lane lined with roses and willow herb. For the war in Normandy is a war of movement. A field reeking with the blood of dead horses and cattle is soon left behind, as the Brigadier stabs his finger at the map and finds another bridge, another crossroads and another copse that must be taken.

aron writes lyrically about the midsummer grace of the French countryside, its orchards and abundance of wild flowers, some of which grace the helmets and tunics of the passing soldiers, their fragility which will contrast cruelly with the total vulnerability of the crumpled and shattered bodies of the men who wore them. For the driven and exhausted men of the Fifth Wessex, unlike their fathers before them, there is always a new unspoiled hillside, a grove of trees untouched by shellfire, a fresh sunken lane lined with roses and willow herb. For the war in Normandy is a war of movement. A field reeking with the blood of dead horses and cattle is soon left behind, as the Brigadier stabs his finger at the map and finds another bridge, another crossroads and another copse that must be taken.

The heroes in From The City, From The Plough come in all shapes and sizes, but there are no winners. Let Alexander Baron (right) have the last word.

The heroes in From The City, From The Plough come in all shapes and sizes, but there are no winners. Let Alexander Baron (right) have the last word.

“Among the rubble, beneath the smoking ruins, the dead of the Fifth Battalion sprawled around the guns they had silenced; dusty, crumpled and utterly without dignity; a pair of boots protruding from a roadside ditch; a body blackened and bent like a chicken burnt in the stove; a face pressed into the dirt; a hand reaching up out of a mass of brick and timbers; a rump thrust ludicrously towards the sky. The living lay among them, speechless, exhausted, beyond grief or triumph, drawing at broken cigarettes and watching with sunken eyes the tanks go by.”

o adapt the words of a former MP, and son of Hull:

o adapt the words of a former MP, and son of Hull:

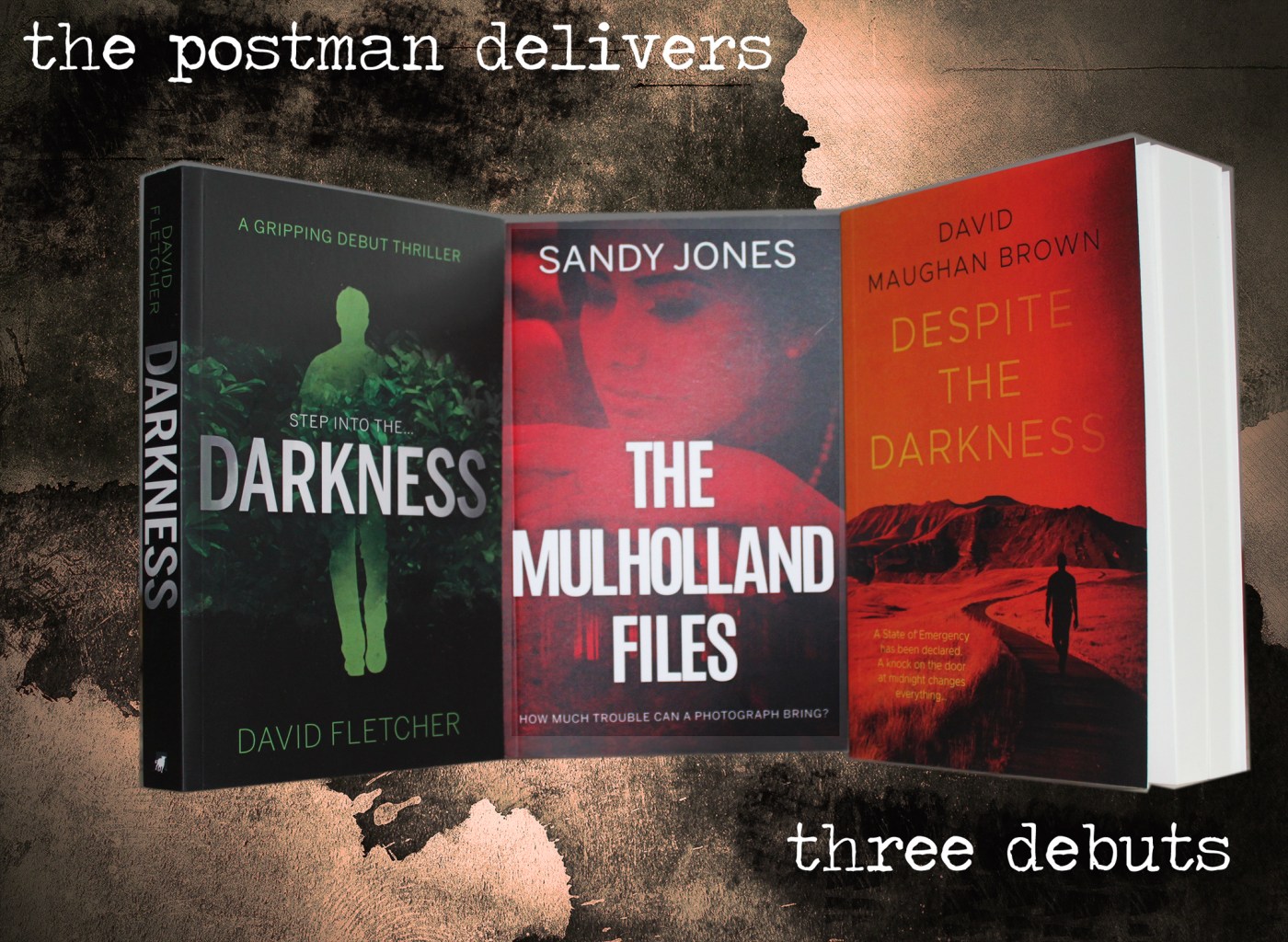

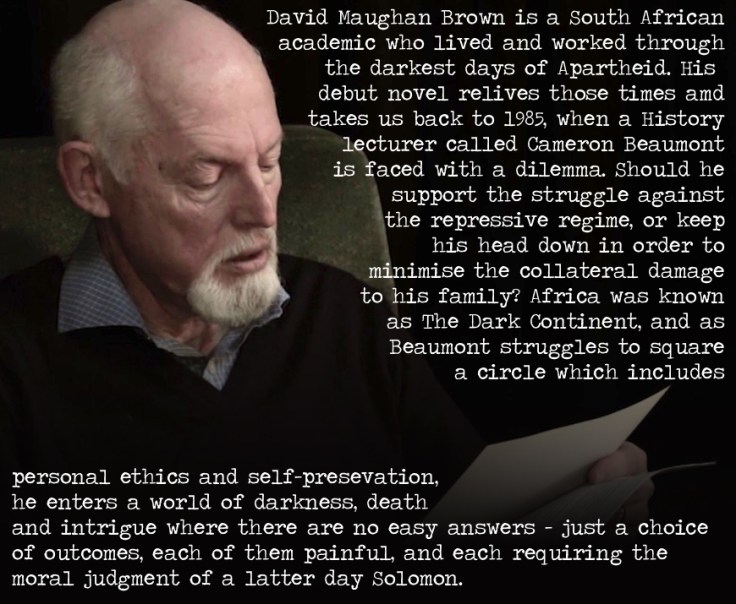

Back when I was at school, scratching on my slate, and climbing up chimneys as a weekend job – OK, OK, I’m exaggerating. My primary school had dip pens, porcelain inkwells and I was the ink monitor. The last bit is actually true, and it’s also true that we could refer to Africa as The Dark Continent without invoking the fury of The Woke. Working on the assumption that Africa was ‘darker’ the further you went into it, then the Congo was blacker than black. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Greene’s A Burnt-Out Case feasted royally on the remoteness of the Congo, and the consequent imaginings of a land where the moral code was either abandoned or perverted. David Fletcher’s Dan Worthington has suffered loss, heartbreak, and the almost surgical removal of his life spirit. A chance encounter offers him a renaissance and a reawakening, but there is a price to be paid. A flight to Brazzaville takes him to the divided modern Congo, and a sequence of events which will test his resolve to its core. Darkness came out on 13th August and is available

Back when I was at school, scratching on my slate, and climbing up chimneys as a weekend job – OK, OK, I’m exaggerating. My primary school had dip pens, porcelain inkwells and I was the ink monitor. The last bit is actually true, and it’s also true that we could refer to Africa as The Dark Continent without invoking the fury of The Woke. Working on the assumption that Africa was ‘darker’ the further you went into it, then the Congo was blacker than black. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Greene’s A Burnt-Out Case feasted royally on the remoteness of the Congo, and the consequent imaginings of a land where the moral code was either abandoned or perverted. David Fletcher’s Dan Worthington has suffered loss, heartbreak, and the almost surgical removal of his life spirit. A chance encounter offers him a renaissance and a reawakening, but there is a price to be paid. A flight to Brazzaville takes him to the divided modern Congo, and a sequence of events which will test his resolve to its core. Darkness came out on 13th August and is available  When Edward Covington opens a letter one winter morning to find it contains only a photograph of an unknown woman he is curious, naturally, but no alarm bells ring. He clearly needs to read more thrillers, as we all know that this is just the beginning of his troubles. Violence, kidnap, ransom, secret codes, industrial espionage, international security alerts – all are about to break rather messily on Edward’s head. Author Sandy Jones (right) lives in the delightful county of Wiltshire, and

When Edward Covington opens a letter one winter morning to find it contains only a photograph of an unknown woman he is curious, naturally, but no alarm bells ring. He clearly needs to read more thrillers, as we all know that this is just the beginning of his troubles. Violence, kidnap, ransom, secret codes, industrial espionage, international security alerts – all are about to break rather messily on Edward’s head. Author Sandy Jones (right) lives in the delightful county of Wiltshire, and

Morag is now Lady Frobisher. Her husband Harry, heir to The Fobisher Estate on the outskirts of Bodmin, is blind, victim of a grenade in the Flanders trenches. In the previous novel, Frobisher Hall was the scene of great torment for Morag, as she fell into the clutches of Morgan Treaves, an insane asylum keeper and his evil nurse. Treaves has disappeared after being disfigured with a broken bottle, wielded my Morag in a life or death struggle.

Morag is now Lady Frobisher. Her husband Harry, heir to The Fobisher Estate on the outskirts of Bodmin, is blind, victim of a grenade in the Flanders trenches. In the previous novel, Frobisher Hall was the scene of great torment for Morag, as she fell into the clutches of Morgan Treaves, an insane asylum keeper and his evil nurse. Treaves has disappeared after being disfigured with a broken bottle, wielded my Morag in a life or death struggle. That said, The Rooks Die Screaming is inspired escapist reading. It would be unfair to say that Tuckett (right) writes in an anachronistic style. This is much, much better than pastiche, even though there are elements of Conan Doyle, the Golden Age, John Buchan and even touches of Sapper and MR James. So, eventually, to the plot, but we need to know a little more about Cyril Edwards. Like many a fictional detective inspector he is his own man. In another nice cultural reference Tuckett adds a touch of Charters and Caldicott as Edwards explains to the bumptious Standish, a mysterious officer from Military Intelligence;

That said, The Rooks Die Screaming is inspired escapist reading. It would be unfair to say that Tuckett (right) writes in an anachronistic style. This is much, much better than pastiche, even though there are elements of Conan Doyle, the Golden Age, John Buchan and even touches of Sapper and MR James. So, eventually, to the plot, but we need to know a little more about Cyril Edwards. Like many a fictional detective inspector he is his own man. In another nice cultural reference Tuckett adds a touch of Charters and Caldicott as Edwards explains to the bumptious Standish, a mysterious officer from Military Intelligence; tandish orders Edwards to investigate the possibility that Harry Frobisher is one of the Rooks, but one who has betrayed his country. Arriving in Bodmin his first task is to explain to the local police how a corpse found on a train is that of a notorious London contract killer. Tuckett’s Bodmin is full of stock characters, including a stolid police sergeant, an apparently tremulous clergyman and a punctilious but respected solicitor who is privy to all the secrets of the local gentry, but is oh, so discreet. To add to the fun, Frobisher Hall also has its requisite roll call of faithful retainers.

tandish orders Edwards to investigate the possibility that Harry Frobisher is one of the Rooks, but one who has betrayed his country. Arriving in Bodmin his first task is to explain to the local police how a corpse found on a train is that of a notorious London contract killer. Tuckett’s Bodmin is full of stock characters, including a stolid police sergeant, an apparently tremulous clergyman and a punctilious but respected solicitor who is privy to all the secrets of the local gentry, but is oh, so discreet. To add to the fun, Frobisher Hall also has its requisite roll call of faithful retainers.