England. 11th April 1981. While the music charts bubble with the froth of Bucks Fizz, Shakin’ Stevens, Adam and the Ants and The Nolans, London – at least the place south of the river called Brixton – is aflame with violence, racial hatred and mayhem. As the police struggle to control the streets a middle aged Detective Inspector called Henry Hobbes is bused in to help. No matter that Hobbes – and many other senior detectives likewise – is a stranger to riot control, it is a case of all hands on deck.

Later that year, with Brixton quieter, despite other English towns and cities erupting in copycat anger, Hobbes has become embroiled in a bitter internal dispute. A fellow copper, Charlie Jenkes (who rescued Hobbs from the mob on that fateful April night) after being indicted for savagely beating a black suspect, has taken his own life. And the officer who testified to Jenkes’s violence? Henry Hobbes, who, with that single act of honesty, is branded as a Judas by his own colleagues.

Later that year, with Brixton quieter, despite other English towns and cities erupting in copycat anger, Hobbes has become embroiled in a bitter internal dispute. A fellow copper, Charlie Jenkes (who rescued Hobbs from the mob on that fateful April night) after being indicted for savagely beating a black suspect, has taken his own life. And the officer who testified to Jenkes’s violence? Henry Hobbes, who, with that single act of honesty, is branded as a Judas by his own colleagues.

But now Hobbes has something to distract him from his disintegrating family life and his pariah status among fellow officers. A young man is found dead, wth his body gruesomely mutilated. Brendon Clarke was a minor celebrity, the lead singer with an aspiring band called Monsoon Monsoon, whose chief claim to fame is that they play the music of another dead rockstar – Lucas Bell. Bell’s celebrity rests on hs apparent suicide, his angst-ridden persona, and, most of all, his adoption of the identity of King Lost, a charismatic figure with a gruesome mask.

As Hobbes tries to unpick the complex knot which ties together the identities of Brendan Clarke and Lucas Bell, he discovers that the King Lost legend has its roots in a bizarre fantasy world created by a group of teenagers in the Sussex town of Hastings. With more murders being linked to the world of King Lost, Hobbes is drawn into an investigation which exposes child abuse, blackmail, madness and revenge.

Genre compartmentalising books is not always helpful, but it is fair to say that Noon’s previous novels have used tropes from science fiction, psychedelia and dystopian fantasy. Slow Motion Ghosts adopts conventions of the police procedural, but is more adventurous, asks more questions and has a distinctly noir-ish feel. Noon uses his knowledge of the music scene to bore down into the strange phenomenon of the celebrity cult, and the lengths to which worshippers of dead heroes are prepared to go in order to keep their fantasies alive.

Jeff Noon was born in Droylsden in 1957. He was trained in the visual arts, and was musically active on the punk scene before starting to write plays for the theatre. His first novel, Vurt, was published in 1993 and went on to win the Arthur C. Clarke Award. He reviews crime fiction for The Spectator.

Slow Motion Ghosts is published by Doubleday, and is out now.

Two children, Sean and Lilly, murder a third child, Luke – disabled physically and mentally. In a case that whips up a storm of public revulsion, both are sentenced to long prison terms. Eventually, both are released on licence subject to supervision. Lilly is now Charlotte, ankle-tagged and nervous about a new world full of strange things that never existed when she lost her liberty all those years ago.

Two children, Sean and Lilly, murder a third child, Luke – disabled physically and mentally. In a case that whips up a storm of public revulsion, both are sentenced to long prison terms. Eventually, both are released on licence subject to supervision. Lilly is now Charlotte, ankle-tagged and nervous about a new world full of strange things that never existed when she lost her liberty all those years ago. Secondly, and inevitably, we are drawn into acting as judge and jury about the complex matter of culpability for Luke’s death. Remember, there is no Him:Then. We only see the young Sean through Lilly’s eyes and it seems, for a time at least, that he is the dangerous one, the wild card, the ten year-old Dark Angel, if you will. For sure, he is not neglected in the sense that his home life attracts the attention of Children’s Services, even though the family routine is haphazard. By contrast, Lilly’s life with her bruised and beaten mother ends in tragedy, although once she has moved in with her aunt she receives love, compassion and care. But is she already too badly damaged from the nightmare of her mother’s death for the new life to heal the wounds?

Secondly, and inevitably, we are drawn into acting as judge and jury about the complex matter of culpability for Luke’s death. Remember, there is no Him:Then. We only see the young Sean through Lilly’s eyes and it seems, for a time at least, that he is the dangerous one, the wild card, the ten year-old Dark Angel, if you will. For sure, he is not neglected in the sense that his home life attracts the attention of Children’s Services, even though the family routine is haphazard. By contrast, Lilly’s life with her bruised and beaten mother ends in tragedy, although once she has moved in with her aunt she receives love, compassion and care. But is she already too badly damaged from the nightmare of her mother’s death for the new life to heal the wounds?

I have become a great fan of the Crampton of the Chronicle mysteries. Despite having multifarious murders and diverse dirty deeds, they are breezy, funny, beautifully written and they have a definite feel-good factor. Peter Bartram (left) is an old newspaper hand himself, and the background of a 1960s newsroom in a provincial newspaper is as authentic as it can get. Colin Crampton’s latest journey into the criminal underworld of Brighton is The Comedy Club Mystery. The cover blurb tells us:

I have become a great fan of the Crampton of the Chronicle mysteries. Despite having multifarious murders and diverse dirty deeds, they are breezy, funny, beautifully written and they have a definite feel-good factor. Peter Bartram (left) is an old newspaper hand himself, and the background of a 1960s newsroom in a provincial newspaper is as authentic as it can get. Colin Crampton’s latest journey into the criminal underworld of Brighton is The Comedy Club Mystery. The cover blurb tells us: “When theatrical agent Daniel Bernstein sues the Evening Chronicle for libel, crime reporter Colin Crampton is called in to sort out the problem.

“When theatrical agent Daniel Bernstein sues the Evening Chronicle for libel, crime reporter Colin Crampton is called in to sort out the problem.

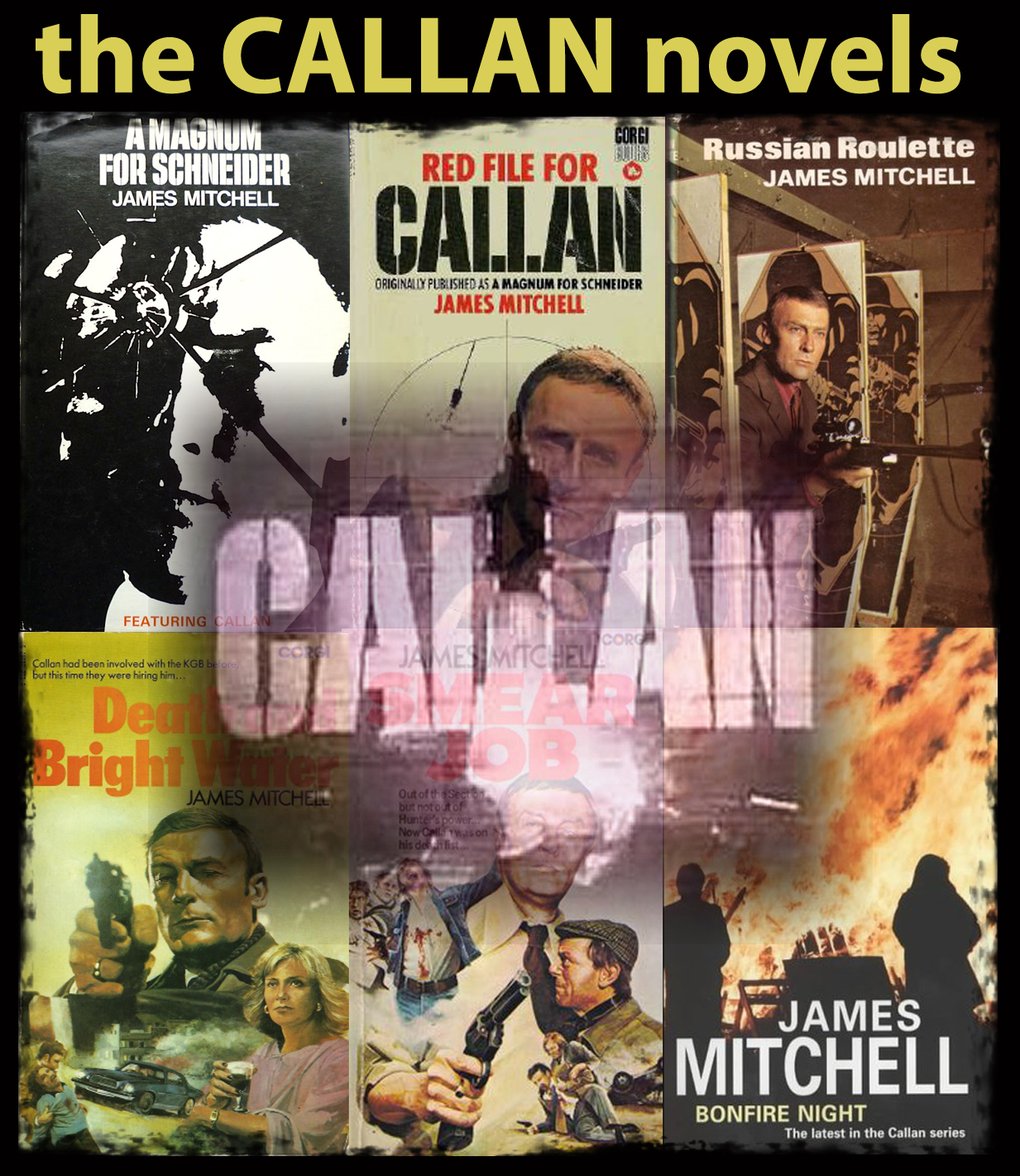

The first Callan novel, and perhaps the locus classicus of all Callan plots, on page and screen: A disillusioned Callan has left the Section and is living and working in reduced circumstances, until “persuaded” by Hunter to return and carry out one more job. The target is Herr Schneider who, once Callan knows more of him, doesn’t seem to be as black as he’s painted…

The first Callan novel, and perhaps the locus classicus of all Callan plots, on page and screen: A disillusioned Callan has left the Section and is living and working in reduced circumstances, until “persuaded” by Hunter to return and carry out one more job. The target is Herr Schneider who, once Callan knows more of him, doesn’t seem to be as black as he’s painted…

Although published in 1973 this book makes no reference to the events of high drama with which the final TV series concluded a year earlier. Here, Callan is still settled in the Section and all the supporting characters are in place.

Although published in 1973 this book makes no reference to the events of high drama with which the final TV series concluded a year earlier. Here, Callan is still settled in the Section and all the supporting characters are in place.

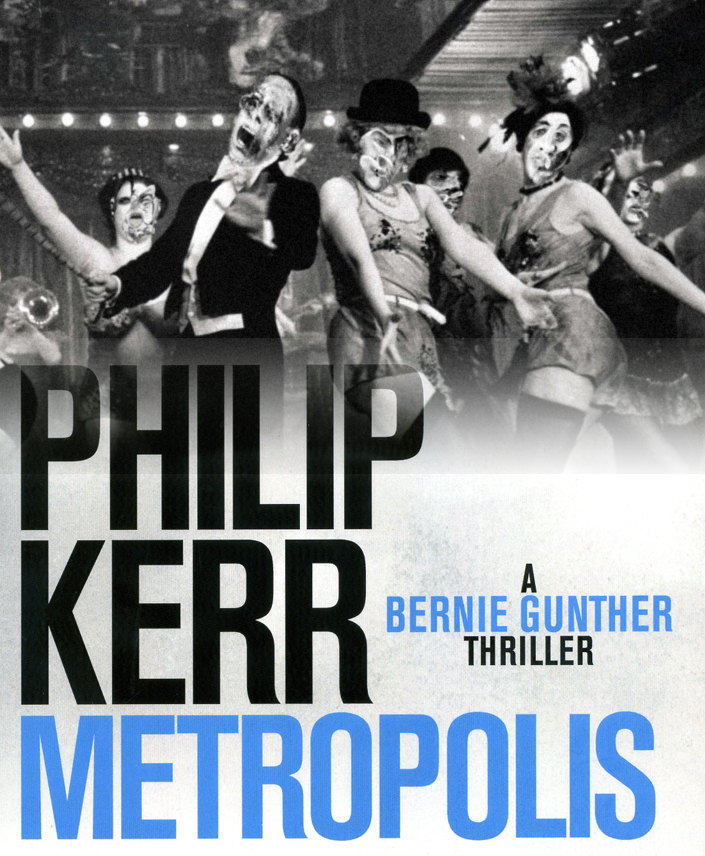

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth?

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth? Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.