David Raker finds people. Mostly these people are lost in physical form: sometimes he finds them alive but sometimes dead, and in the seven Raker novels which preceded I Am Missing, author Tim Weaver has composed variations on this theme. Now, however, Raker’s latest client is very visible and tangible, if a little careworn. Richard Kite has a big problem. He has no idea who he is or who he was. Found lying on the shingle shore near Southampton Water, bruised, battered and barely conscious, he was briefly the hot property of the tabloid press, starring as a nine day wonder before the media and their public grew bored of the tale and moved on to fresh sensations.

Raker agrees to take on the case on a more-or-less pro bono basis. Whatever and whoever Richard Kite once was, he has not brought wealth of any kind with him into his new life. Raker’s initial trip south to meet Kite is less than fruitful. Kite only recalls two shadowy images from his past; one is that he is looking out across a lonely beach to a grey expanse of water; is it the sea, perhaps, or a river? The other image is just as enigmatic; Kite sees a television screen, and on it is a graphic of a broadcasting pylon emitting what seems to be a children’s programme.

Raker agrees to take on the case on a more-or-less pro bono basis. Whatever and whoever Richard Kite once was, he has not brought wealth of any kind with him into his new life. Raker’s initial trip south to meet Kite is less than fruitful. Kite only recalls two shadowy images from his past; one is that he is looking out across a lonely beach to a grey expanse of water; is it the sea, perhaps, or a river? The other image is just as enigmatic; Kite sees a television screen, and on it is a graphic of a broadcasting pylon emitting what seems to be a children’s programme.

Raker is a different kind of investigator. His background is not security, law enforcement or military. His previous career was in journalism, and this means that his cases are rarely settled by force of arms or fisticuffs. Instead, he has a sharp eye for inconsistencies in statements and accounts from the people he deals with, and he can usually spot a lie or an evasion at a hundred paces. When he discovers that Kite has been receiving therapy from a distinguished psychotherapist, he makes an appointment to see her and, within just a few minutes of the interview starting, he senses that she is not telling him everything she knows.

Meanwhile, Weaver (right) gives us what seems to be a parallel but unconnected narrative. Two girls, sister and step sister, apparently living in a remote moorland community, perhaps in the north of England, have taken to sneaking out of their house after dark, and climbing up the hill onto the moors, where they have constructed an imaginary and malevolent presence out there in the wind and rain-swept darkness. Malevolent it certainly seems to be, but is it just a figment of the girls’ lurid imaginings?

Meanwhile, Weaver (right) gives us what seems to be a parallel but unconnected narrative. Two girls, sister and step sister, apparently living in a remote moorland community, perhaps in the north of England, have taken to sneaking out of their house after dark, and climbing up the hill onto the moors, where they have constructed an imaginary and malevolent presence out there in the wind and rain-swept darkness. Malevolent it certainly seems to be, but is it just a figment of the girls’ lurid imaginings?

At this point, with Raker’s investigation about as productive as trying to extract blood from a stone, I will call a halt to the plot synopsis. This is because Weaver has made a beautifully designed surprise for us. It was a shift that I never saw coming, and it is one which makes the final third of the book totally compelling. Fans of the series will be pleased to learn that we get the almost de rigeur exploration of a part of underground London that has been hidden, neglected and forgotten but, having given us this, Weaver makes certain we are all safely seated expecting one thing, before using his smoke and mirrors to reveal something else altogether.

You can check buying choices by clicking the link below.

I AM MISSING

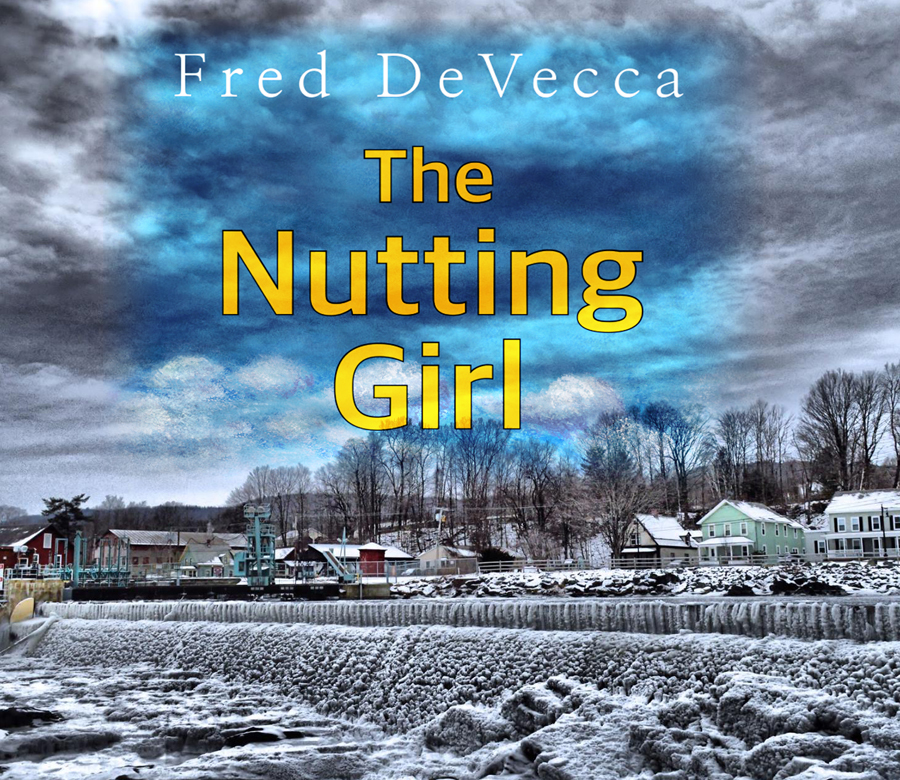

Raven’s job seems like money for nothing until the fateful day when, after a spell of heavy rain, the normally placid stream running through Shelburne Falls is turned into a deadly torrent. ‘Velcro’ ends up in the water, and disappears. Did she fall? Was she pushed? Or is there another more disturbing and puzzling solution? Frank Raven, with the help of Sarah, the eighteen year-old daughter of Clara (Raven’s love interest), unlocks the door to a labyrinth of deception, false identities, dark motives and venal behaviour which they work their way through more in the spirit of hope than the expectation of ever finding the door marked ‘Exit’.

Raven’s job seems like money for nothing until the fateful day when, after a spell of heavy rain, the normally placid stream running through Shelburne Falls is turned into a deadly torrent. ‘Velcro’ ends up in the water, and disappears. Did she fall? Was she pushed? Or is there another more disturbing and puzzling solution? Frank Raven, with the help of Sarah, the eighteen year-old daughter of Clara (Raven’s love interest), unlocks the door to a labyrinth of deception, false identities, dark motives and venal behaviour which they work their way through more in the spirit of hope than the expectation of ever finding the door marked ‘Exit’. Finding a new path through the undergrowth of PI novels, overgrown as it is with violent, cynical, wisecracking and tough, amoral men (and women) must be a difficult task, but Fred De Vecca (right) makes his way with a minimum of fuss and bother. Frank Raven rarely raises his voice, let alone his fists, but his intelligence and empathy with decent people shines through like a beacon in a storm. It would be a forgivable mistake to place this novel in the pile marked ‘Cosy small-town domestic drama’, but it is a mistake, nonetheless. Of the people Raven is tasked with looking for, he finds some and loses some – because he is human, fallible and as susceptible to professional bullshitters as the next guy. What he does find, most importantly, is a kind of personal salvation, and a renewal of his belief in people, and their capacity to change.

Finding a new path through the undergrowth of PI novels, overgrown as it is with violent, cynical, wisecracking and tough, amoral men (and women) must be a difficult task, but Fred De Vecca (right) makes his way with a minimum of fuss and bother. Frank Raven rarely raises his voice, let alone his fists, but his intelligence and empathy with decent people shines through like a beacon in a storm. It would be a forgivable mistake to place this novel in the pile marked ‘Cosy small-town domestic drama’, but it is a mistake, nonetheless. Of the people Raven is tasked with looking for, he finds some and loses some – because he is human, fallible and as susceptible to professional bullshitters as the next guy. What he does find, most importantly, is a kind of personal salvation, and a renewal of his belief in people, and their capacity to change.

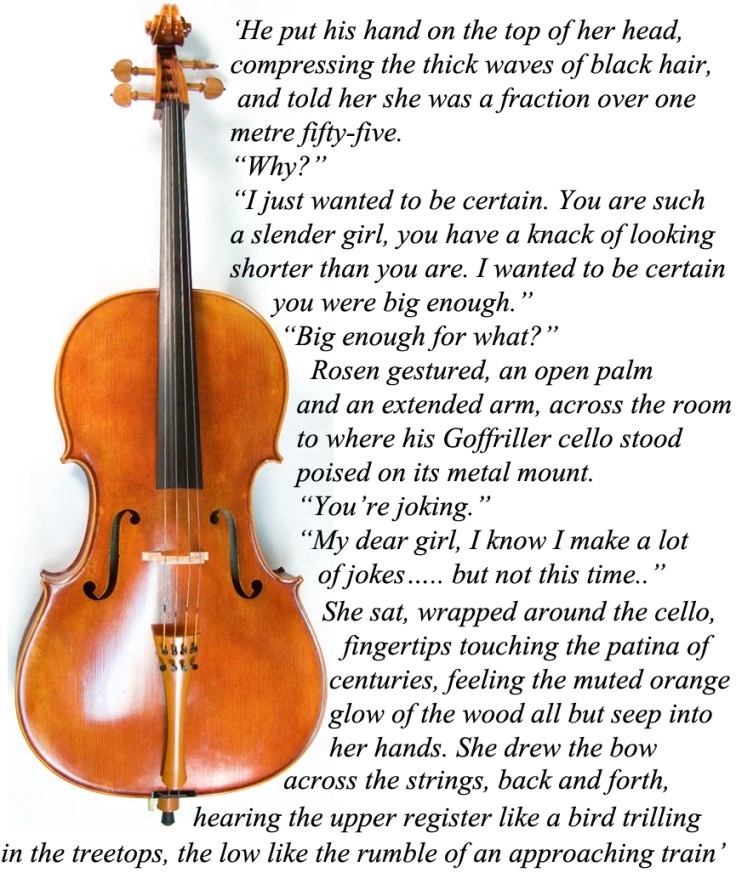

John Lawton is a master of historical fiction set in and around World War II. His central character is Fred Troy, a policeman of Russian descent. His emigré father is what used to be called a ‘Press Baron’. Fred’s brother Rod will go on to become a Labour Party MP in the 1960s, but is interned during the war. His sisters are bit players, but memorable for their sexual voracity. Neither man nor woman is safe from their advances.

John Lawton is a master of historical fiction set in and around World War II. His central character is Fred Troy, a policeman of Russian descent. His emigré father is what used to be called a ‘Press Baron’. Fred’s brother Rod will go on to become a Labour Party MP in the 1960s, but is interned during the war. His sisters are bit players, but memorable for their sexual voracity. Neither man nor woman is safe from their advances.

If the South London suburb of Menham could be described as unremarkable, then we might call the down-at-heel terraced houses of Barley Street positively nondescript. Except, that is, for number 29. For a while, the home of Mary Wasson and her daughters became as notorious as 112 Ocean Avenue, Amityville. But the British tabloid press being what it is, there are always new horrors, fresh outrages and riper scandals, and so the focus moved on. The facts, however, were this. After a spell of unexplained poltergeist phenomena turned the house (almost literally) upside down, the body of nine year-old Holly Wasson was found – by her older sister Rachel – hanging from a beam in her bedroom.

If the South London suburb of Menham could be described as unremarkable, then we might call the down-at-heel terraced houses of Barley Street positively nondescript. Except, that is, for number 29. For a while, the home of Mary Wasson and her daughters became as notorious as 112 Ocean Avenue, Amityville. But the British tabloid press being what it is, there are always new horrors, fresh outrages and riper scandals, and so the focus moved on. The facts, however, were this. After a spell of unexplained poltergeist phenomena turned the house (almost literally) upside down, the body of nine year-old Holly Wasson was found – by her older sister Rachel – hanging from a beam in her bedroom. Laws (right) takes a leaf out of the book of the master of atmospheric and haunted landscapes, M R James. The drab suburban topography of Menham comes alive with all manner of dark interventions; we jump as a wayward tree branch scrapes like a dead hand across a gazebo roof; we recoil in fear as a white muslin curtain forms itself into something unspeakable; dead things scuttle and scrabble about in dark corners while, in our peripheral vision, shapes form themselves into dreadful spectres. When we turn our heads, however, there is nothing there but our own imagination.

Laws (right) takes a leaf out of the book of the master of atmospheric and haunted landscapes, M R James. The drab suburban topography of Menham comes alive with all manner of dark interventions; we jump as a wayward tree branch scrapes like a dead hand across a gazebo roof; we recoil in fear as a white muslin curtain forms itself into something unspeakable; dead things scuttle and scrabble about in dark corners while, in our peripheral vision, shapes form themselves into dreadful spectres. When we turn our heads, however, there is nothing there but our own imagination.

The Nutting Girl by Fred de Vecca

The Nutting Girl by Fred de Vecca Lights Out Summer by Rich Zahradnik

Lights Out Summer by Rich Zahradnik Dadgummit by Maggie Toussaint

Dadgummit by Maggie Toussaint

In Unleashed, his scepticism is shaken by events at an otherwise unremarkable terraced house in South London where, several years ago, a troubled nine-year-old girl committed suicide in the midst of a troubling sequence of poltergeist phenomena.

In Unleashed, his scepticism is shaken by events at an otherwise unremarkable terraced house in South London where, several years ago, a troubled nine-year-old girl committed suicide in the midst of a troubling sequence of poltergeist phenomena.

Eddie is Eddie Newcott, the boy who used to live across the street in Chicory Lane, Limite. The boy who was just a bit different from all the other kids at school. The kid whose dad was a rough and abusive oilfield mechanic. The kid whose mom turned to the bottle to escape her violent husband and the beatings he handed out to their only child. But that was then. Now sees Eddie fallen on hard times. Times so hard that he achieved brief notoriety in the tabloid press, and has now been sentenced to death by lethal injection for murdering his pregnant girlfriend, slashing her open, dragging the foetus out and then arranging the two corpses on his front lawn, posed in an obscene mockery of a Nativity tableau. And it was Christmas Eve.

Eddie is Eddie Newcott, the boy who used to live across the street in Chicory Lane, Limite. The boy who was just a bit different from all the other kids at school. The kid whose dad was a rough and abusive oilfield mechanic. The kid whose mom turned to the bottle to escape her violent husband and the beatings he handed out to their only child. But that was then. Now sees Eddie fallen on hard times. Times so hard that he achieved brief notoriety in the tabloid press, and has now been sentenced to death by lethal injection for murdering his pregnant girlfriend, slashing her open, dragging the foetus out and then arranging the two corpses on his front lawn, posed in an obscene mockery of a Nativity tableau. And it was Christmas Eve. Like Shelby Truman, Raymond Benson (right) is a highly successful writer. He has written thrillers under his own name, most notably his Black Stiletto Saga, and has also written novels based on video games. He has taken up the baton from authors who are no longer with us, like Tom Clancy, and has written several James Bond stories which have either been based on established screenplays – like Die Another Day – or standalone original stories such as The Man With The Red Tattoo.

Like Shelby Truman, Raymond Benson (right) is a highly successful writer. He has written thrillers under his own name, most notably his Black Stiletto Saga, and has also written novels based on video games. He has taken up the baton from authors who are no longer with us, like Tom Clancy, and has written several James Bond stories which have either been based on established screenplays – like Die Another Day – or standalone original stories such as The Man With The Red Tattoo.

So, when Gabriel answers the door bell one day only to behold the wedge-shaped and granite faced personage of Farrelly – chauffeur, enforcer and general gofer for Frank Parr – he is led, like a naughty boy tweaked by his ear, to Parr’s sumptious office building. To say that Parr – now a respectable media mogul – has something of a history, is rather like saying that Vlad The Impaler was someone of interest to Amnesty International. Parr made his money – loads of it, and of the distinctly dirty variety – by publishing magazines which were not so much Top Shelf as stacked in the stratosphere miles above the earth’s surface.

So, when Gabriel answers the door bell one day only to behold the wedge-shaped and granite faced personage of Farrelly – chauffeur, enforcer and general gofer for Frank Parr – he is led, like a naughty boy tweaked by his ear, to Parr’s sumptious office building. To say that Parr – now a respectable media mogul – has something of a history, is rather like saying that Vlad The Impaler was someone of interest to Amnesty International. Parr made his money – loads of it, and of the distinctly dirty variety – by publishing magazines which were not so much Top Shelf as stacked in the stratosphere miles above the earth’s surface. “For a while, I wandered the streets of Soho, as I had on the day I’d first visited forty years ago. Doorways whispered to me and ghosts looked down from high windows.”

“For a while, I wandered the streets of Soho, as I had on the day I’d first visited forty years ago. Doorways whispered to me and ghosts looked down from high windows.”

When the battered body of teenager Melanie Cooke is found amid the garbage bins in a seedy Bristol alleyway, it is obvious that she has been murdered. Only fourteen, she is dressed in the kind of clothes which would be considered provocative on a woman twice her age. Vogel goes to make the dreaded ‘death call’, but he only has to appear on the doorstep of the girl’s home for her mother and father to sense the worst. Like many rebellious teenagers before her, Melanie has told her parents that she is going round to a mate’s house to do some homework. When she failed to come home, their first ‘phone call confirmed Melanie’s lie, and thereafter, the long dark hours of the night are spent in increasing anxiety and then terror, as they realise that something awful has happened.

When the battered body of teenager Melanie Cooke is found amid the garbage bins in a seedy Bristol alleyway, it is obvious that she has been murdered. Only fourteen, she is dressed in the kind of clothes which would be considered provocative on a woman twice her age. Vogel goes to make the dreaded ‘death call’, but he only has to appear on the doorstep of the girl’s home for her mother and father to sense the worst. Like many rebellious teenagers before her, Melanie has told her parents that she is going round to a mate’s house to do some homework. When she failed to come home, their first ‘phone call confirmed Melanie’s lie, and thereafter, the long dark hours of the night are spent in increasing anxiety and then terror, as they realise that something awful has happened. The book actually starts with a prologue which at first glance appears to be nothing to do with Melanie’s death. It is only later – much later – that we learn its true significance. Bonner (right) is determined not to give us a straightforward narrative. The progress of Vogel’s attempts to find Melanie’s killer are sandwiched between accounts from three different men, each of whom is living a life where all is not as it seems.

The book actually starts with a prologue which at first glance appears to be nothing to do with Melanie’s death. It is only later – much later – that we learn its true significance. Bonner (right) is determined not to give us a straightforward narrative. The progress of Vogel’s attempts to find Melanie’s killer are sandwiched between accounts from three different men, each of whom is living a life where all is not as it seems.