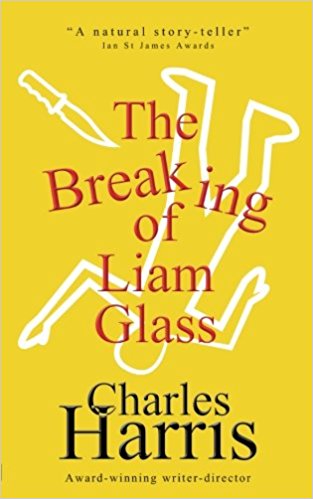

For the eternal pessimist Thomas Hardy it was simply ‘fate’. For the American sociologist Robert K. Morton, however it was The Law of Unintended Consequences. For single mum Katriona ‘Kati’ Glass, sitting in her dispiriting and down-at-heel London flat in an area known as ‘The Estates’, it was a simple mistake, a memory lapse, a silly slip of the mind, a tired thought from a tired woman living a tired life. She forgets that the pizza delivery man takes plastic.

Charles Harris (right), a best-selling non-fiction author and writer-director for film and television sets in train a disastrous serious of mishaps, each of which stems from Kati’s ostensibly harmless error. Too exhausted from her daily grind making sure that Every Little Helps at everyone’s favourite supermarket, she sends her hapless son, Liam, off to the cashpoint, armed with her debit card and its vital PIN. Sadly, Liam never makes it home with the cash, the pizza guy remains unpaid, and Kati Glass is pitched into a nightmare.

Charles Harris (right), a best-selling non-fiction author and writer-director for film and television sets in train a disastrous serious of mishaps, each of which stems from Kati’s ostensibly harmless error. Too exhausted from her daily grind making sure that Every Little Helps at everyone’s favourite supermarket, she sends her hapless son, Liam, off to the cashpoint, armed with her debit card and its vital PIN. Sadly, Liam never makes it home with the cash, the pizza guy remains unpaid, and Kati Glass is pitched into a nightmare.

Liam is found stabbed and minutes away from death. What follows is not so much a conventional crime novel, but a journey through a dystopian world inhabited by people who we might spot in a crowded street and think, “I know that person, but where did we meet?” Central to the story is Jason Worthington, a journalist on a London local paper, The Camden Herald. The Herald is struggling to survive in a world where news – both false and otherwise – is flashed around the city from phone to phone before the conventional press can even tap out the beginnings of a story. Everything he ever wanted to be as a reporter – courageous, hard-hitting, a fighter for justice – is blocked by his newspaper bosses who, terrified of upsetting their advertisers, want only stories about cuddly kittens, school nativity plays and giant cheques being presented to worthy causes.

Trying to find out who stabbed Liam Glass is Detective Constable Andy Rackham. He is a walking tick-box of all the difficulties faced by an ambitious copper trying to please his bosses while being a supportive husband and father. The third member of this unholy trinity is Jamila Hasan, an earnest politician of Bengali origin who senses that the attack might be just the campaign platform she needs to ensure that she is re-elected. But what if Liam’s attackers are from her own community? Sadly, in her efforts to gain credibility on the street, Jamila has been duped.

Trying to find out who stabbed Liam Glass is Detective Constable Andy Rackham. He is a walking tick-box of all the difficulties faced by an ambitious copper trying to please his bosses while being a supportive husband and father. The third member of this unholy trinity is Jamila Hasan, an earnest politician of Bengali origin who senses that the attack might be just the campaign platform she needs to ensure that she is re-elected. But what if Liam’s attackers are from her own community? Sadly, in her efforts to gain credibility on the street, Jamila has been duped.

‘“Respec’ for the brothas and sistas that fight the cause. Dis am Gian’killa Mo broadcastin’ from Free Sout’ Camden …..” For months Jamila had listened to Gian’killa Mo, broadcasting illegally from the Estates. It had made her feel in-with-the-hood, until the day she visited a small flat above Sainsbury’s Local, where Gian’killa Mo turned out to be a fifty-three-year-old white primary schoolteacher with a degree in Greek drama and a room full of old valve radios.’

As Liam Glass lies in his hospital bed, kept alive only by a bewildering array of tubes and bleeping monitors, Worthington, Rackham and Hasan flutter around the light of the central tragedy like so many moths. Each is dependant on Liam’s fate in their desperate scrambling for the next rung on their career ladder. Harris has clearly spent many a productive hour in the company of journalists and he lampoons the peculiar language beloved of tabloid headline writers. Should Liam’s absent father actually prove to be a football star, how best to head up the story? Two reporters toss ideas back and forth between them:

“Premiership Love Rat Abandoned Son To Life Of Violence,’’ added Zoe with more relish than Jason thought was necessary.

‘We don’t want to be too hard on the father,’ he offered with a tremor of concern. ‘What about “Top Player’s Pain Over Stabbed Son”?’

‘” Love Child Booted Into Touch”,’ said Snipe. ‘”Cast Off Son Pays Ultimate Penalty”,’

‘” Secret Grief Of England Star”?’ suggested Jason hopefully.

In the wake of the attack on Liam Glass, tensions rise on The Estates. Jamila convenes a meeting which she hopes will calm tempers and cast her in the role of peacemaker. Inevitably, the meeting descends into chaos and then farce, as the different factions shake each other warmly by the throat. Harris saves his fiercest scorn for the concept of Community Leaders. Observing that solid, upstanding suburbs have little need for anyone to lead them, he says:

“The Estates….spawned dozens, scores, hundreds. They boasted elected leaders and appointed leaders, self-styled leaders and would-be leaders. They acquired a couple of reluctant leaders (usually the best, and in short supply). They developed voluble leaders and argumentative leaders, attractive leaders, inspirational leaders and scary leaders. There were even a few leaders who knew what they were talking about.”

The back cover of the novel likens this book to Catch 22. That claim may be a little ambitious, but The Breaking of Liam Glass is a brilliant satire on modern Britain, scabrously funny, full of venom and a crunching smack in the mouth for those who seek to protect certain ideas and practices from criticism. Perhaps nothing will ever rival Joseph Heller’s masterpiece, but Harris’s novel shares one vital element. Remember how, after hundreds of pages of surreal humor, Catch 22 suddenly darkens, and leads readers into one of the blackest places they will ever have visited? So it is with The Breaking of Liam Glass. You will laugh at the knockabout fun that Harris has with the ridiculous state of modern Britain, but in the final pages all fades to black and a shiver will run through your bones.

The Breaking of Liam Glass is from Marble City Publishing, and is available here.

Jean-Jacques ‘JJ’ Stoner is a stone cold killer. His creator, Frank Westworth gives us a first glimpse of him as an army sergeant serving in Iraq. One of his squad has just been fatally wounded by a knife thrown by one of a group of Iraqis who:

Jean-Jacques ‘JJ’ Stoner is a stone cold killer. His creator, Frank Westworth gives us a first glimpse of him as an army sergeant serving in Iraq. One of his squad has just been fatally wounded by a knife thrown by one of a group of Iraqis who:

It doesn’t take a genius to work out that Westworth (right) is deeply immersed in the lore and legend of pop music as well as knowing his guitars. The Killing Sisters books are scattered with references – some subtle, but others more obvious – to great songs and singers. Later in The Redemption of Charm, Stoner renews his acquaintance with his favourite guitar:

It doesn’t take a genius to work out that Westworth (right) is deeply immersed in the lore and legend of pop music as well as knowing his guitars. The Killing Sisters books are scattered with references – some subtle, but others more obvious – to great songs and singers. Later in The Redemption of Charm, Stoner renews his acquaintance with his favourite guitar: Colin Dexter’s stories of the wonderful curmudgeon are among the widest read in the last quarter of the 20th century, but less well known are the Vienna-set novels of Frank Tallis featuring policeman Oskar Rheinhardt and his young pyschiatrist friend Dr Max Liebermann. The younger man often plays piano for Rheinhardt melodic baritone as they seek solace from the stresses and strains of catching murderers.

Colin Dexter’s stories of the wonderful curmudgeon are among the widest read in the last quarter of the 20th century, but less well known are the Vienna-set novels of Frank Tallis featuring policeman Oskar Rheinhardt and his young pyschiatrist friend Dr Max Liebermann. The younger man often plays piano for Rheinhardt melodic baritone as they seek solace from the stresses and strains of catching murderers.

Annemarie Neary gives us a chilling sense of separate events which are not fatal in themselves but deadly when they collide, and while Ro is making his way to Clapham, the normally self-assured Jess is in trouble at work. She has rejected the advances of a senior partner at an office social, and he uses the rebuff to light a fire under Jess’s professional life.

Annemarie Neary gives us a chilling sense of separate events which are not fatal in themselves but deadly when they collide, and while Ro is making his way to Clapham, the normally self-assured Jess is in trouble at work. She has rejected the advances of a senior partner at an office social, and he uses the rebuff to light a fire under Jess’s professional life.

When we next meet Charles it is 1964, and much has changed. The streets of the old East End, having been substantially rearranged by Hitler’s bombs, have been redeveloped. More significantly, the Jewish people have largely moved on. Many families have prospered and they have moved out to the comfortable suburbs. Charles Horowitz has also prospered, after a fashion. His chosen career is Law, and in order to rise through the ranks of the socially and ethnically tightly knit Inns of Court, he has abandoned Horowitz and reinvented himself as Charles Holborne.

When we next meet Charles it is 1964, and much has changed. The streets of the old East End, having been substantially rearranged by Hitler’s bombs, have been redeveloped. More significantly, the Jewish people have largely moved on. Many families have prospered and they have moved out to the comfortable suburbs. Charles Horowitz has also prospered, after a fashion. His chosen career is Law, and in order to rise through the ranks of the socially and ethnically tightly knit Inns of Court, he has abandoned Horowitz and reinvented himself as Charles Holborne. for those who want to complete the picture, but with The Lighterman it is sufficient to say that Charles has made a very undesirable enemy. It is probably merely an exercise in semantics to distinguish between the equally awful twin sons of Charles David Kray and Violet Annie Lee, but most casual observers agree that Ronnie was the worst of two evils. The homosexual, paranoid and pathologically violent gangster has a list of people who have upset him. The first name on that list is none other than Charles Holborne aka Horowitz, and the brutal East End hoodlum is determined that Charles must be done away with.

for those who want to complete the picture, but with The Lighterman it is sufficient to say that Charles has made a very undesirable enemy. It is probably merely an exercise in semantics to distinguish between the equally awful twin sons of Charles David Kray and Violet Annie Lee, but most casual observers agree that Ronnie was the worst of two evils. The homosexual, paranoid and pathologically violent gangster has a list of people who have upset him. The first name on that list is none other than Charles Holborne aka Horowitz, and the brutal East End hoodlum is determined that Charles must be done away with. Simon Michael (left) combines an encyclopaedic knowledge of London, with an insider’s grasp of courtroom proceedings. I cannot say if it was the author’s intention – only he can concur or disagree – but his writing left me with a profound sense of sadness over what London’s riverside and its East End once were – and what they have become. This is a beautifully written novel which succeeds on three different levels. Firstly, it is a superb recreation of a London which is just a lifetime away, but may as well be the Egypt of the pharaohs, such is its distance from us. Secondly, it is a tense and authentic legal thriller, with all the nuances and delicate sensibilities of the British legal system pushed into the spotlight. Thirdly – and perhaps most importantly – we meet characters who are totally convincing, speak in a manner which sounds authentic, and have all the qualities and flaws which we recognise in people of our own acquaintance. The Lighterman is published by Urbane Publications and is

Simon Michael (left) combines an encyclopaedic knowledge of London, with an insider’s grasp of courtroom proceedings. I cannot say if it was the author’s intention – only he can concur or disagree – but his writing left me with a profound sense of sadness over what London’s riverside and its East End once were – and what they have become. This is a beautifully written novel which succeeds on three different levels. Firstly, it is a superb recreation of a London which is just a lifetime away, but may as well be the Egypt of the pharaohs, such is its distance from us. Secondly, it is a tense and authentic legal thriller, with all the nuances and delicate sensibilities of the British legal system pushed into the spotlight. Thirdly – and perhaps most importantly – we meet characters who are totally convincing, speak in a manner which sounds authentic, and have all the qualities and flaws which we recognise in people of our own acquaintance. The Lighterman is published by Urbane Publications and is

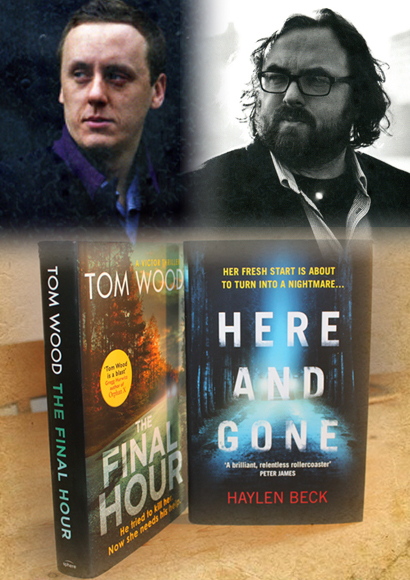

The first is The Final Hour by Tom Wood. It is apparently the seventh in a series of thrillers centred on an international assassin called Victor. I confess that I am new to the books, but it seems that Victor, after a string of successful ice-cold hits has developed a painful affliction for any paid killer – he has started to show remorse. CIA man Antonio Alvarez is as remorseless a hunter – but in the cause of good – as Victor, but now circumstances dictate that their orbits will collide, with devastating effect. The Final Hour is published by Sphere, and is out on 29th June.

The first is The Final Hour by Tom Wood. It is apparently the seventh in a series of thrillers centred on an international assassin called Victor. I confess that I am new to the books, but it seems that Victor, after a string of successful ice-cold hits has developed a painful affliction for any paid killer – he has started to show remorse. CIA man Antonio Alvarez is as remorseless a hunter – but in the cause of good – as Victor, but now circumstances dictate that their orbits will collide, with devastating effect. The Final Hour is published by Sphere, and is out on 29th June. As I flicked through the pages of Here and Gone I saw the author photo on the back inside cover, and I thought, “hang on, I know that bloke..” I’ve not had the pleasure of meeting Stuart Neville in person, but I have become a great admirer of his crime thrillers set in Ireland, both north and south of the border. But now, here he is, under the name of Haylen Beck, with a novel which he says is inspired by his love of American crime fiction.

As I flicked through the pages of Here and Gone I saw the author photo on the back inside cover, and I thought, “hang on, I know that bloke..” I’ve not had the pleasure of meeting Stuart Neville in person, but I have become a great admirer of his crime thrillers set in Ireland, both north and south of the border. But now, here he is, under the name of Haylen Beck, with a novel which he says is inspired by his love of American crime fiction.

The muster room of hard-nosed female cops and investigators is not exactly a crowded place on Planet CriFi. Victoria Iphigenia Warshawski, Fiona Griffiths, Kate Brannigan, Cordelia Gray, Kay Scarpetta and Jane Marple have already taken their seats, but Temperance Brennan has, temporarily, given up hers for another child of her creator, Kathy Reichs (left). Sunday ‘Sunnie’ Night is a damaged, bitter, edgy and downright misanthropic American cop who has been suspended by her bosses for being trigger happy. She sits brooding, remote – and dangerous – on a barely accessible island off the South Carolina coast.

The muster room of hard-nosed female cops and investigators is not exactly a crowded place on Planet CriFi. Victoria Iphigenia Warshawski, Fiona Griffiths, Kate Brannigan, Cordelia Gray, Kay Scarpetta and Jane Marple have already taken their seats, but Temperance Brennan has, temporarily, given up hers for another child of her creator, Kathy Reichs (left). Sunday ‘Sunnie’ Night is a damaged, bitter, edgy and downright misanthropic American cop who has been suspended by her bosses for being trigger happy. She sits brooding, remote – and dangerous – on a barely accessible island off the South Carolina coast. Half way through the novel we realise the significance of the title. Sunnie Night is not waging this war alone: her twin brother Augustus ‘Gus’ Night is also on the case and, to use the cliche, he ‘has her back’. Together they are certainly a deadly combination. By this point, though, Reichs has bowled us an unreadable googly – or, for American readers, thrown us a curveball – and it isn’t until the closing pages that we realise that we have been making incorrect assumptions. Which is, of course, exactly what the author planned! Those last few pages make for a terrific finale, as the twins desperately try to prevent an atrocity being carried out at one of America’s most celebrated sporting occasions.

Half way through the novel we realise the significance of the title. Sunnie Night is not waging this war alone: her twin brother Augustus ‘Gus’ Night is also on the case and, to use the cliche, he ‘has her back’. Together they are certainly a deadly combination. By this point, though, Reichs has bowled us an unreadable googly – or, for American readers, thrown us a curveball – and it isn’t until the closing pages that we realise that we have been making incorrect assumptions. Which is, of course, exactly what the author planned! Those last few pages make for a terrific finale, as the twins desperately try to prevent an atrocity being carried out at one of America’s most celebrated sporting occasions.

Stoddart wears his scholarship lightly in the crime novels, but he is a gifted and compelling writer when dealing with the real world. In A House in Damascus – Before the Fall (2012) he examines the tragedy of the Syrian conflict and its effect on ordinary people for whom the complex political issues mean nothing but shattered lives, hardship – and death.

Stoddart wears his scholarship lightly in the crime novels, but he is a gifted and compelling writer when dealing with the real world. In A House in Damascus – Before the Fall (2012) he examines the tragedy of the Syrian conflict and its effect on ordinary people for whom the complex political issues mean nothing but shattered lives, hardship – and death. steel and bullets with nothing but their manly chests. Don Bradman and Bill Woodfull, plucky Australian lads, direct descendants of the ANZACS, faced the barrage of Larwood and Voce with nothing but a small piece of shaped willow wood. Stoddart co-authored, with Ric Sissons, Cricket and Empire, an account of this bitter battle.

steel and bullets with nothing but their manly chests. Don Bradman and Bill Woodfull, plucky Australian lads, direct descendants of the ANZACS, faced the barrage of Larwood and Voce with nothing but a small piece of shaped willow wood. Stoddart co-authored, with Ric Sissons, Cricket and Empire, an account of this bitter battle.

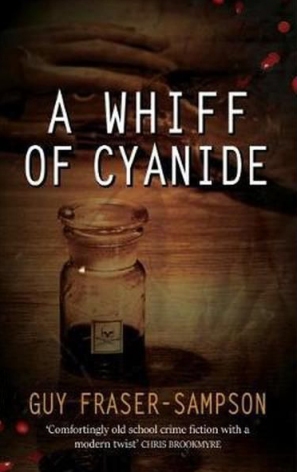

Readers of the two previous books in the Hampstead Murders series, Death In Profile and Miss Christie Regrets, will know what to expect, but for readers new to the novels here is a Bluffers’ Guide. The stories are set in modern day Hampstead, a very select and expensive district of London. The police officers involved are, principally, Detective Superintendent Simon Collison, a civilised and gentlemanly type who, despite his charm and urbanity, is reluctant to climb the promotion ladder which is presented to him. Detective Sergeant Karen Willis is, likewise, of finishing school material, but also a very good copper with – as we are often reminded – legs to die for. She is in love, but not exclusively, with Detective Inspector Bob Metcalfe, a decent sort with a heart of gold. If he were operating back in the Bulldog Drummond era he would certainly have a lantern jaw and blue eyes that could be steely, or twinkle with kindness as circumstances dictate.

Readers of the two previous books in the Hampstead Murders series, Death In Profile and Miss Christie Regrets, will know what to expect, but for readers new to the novels here is a Bluffers’ Guide. The stories are set in modern day Hampstead, a very select and expensive district of London. The police officers involved are, principally, Detective Superintendent Simon Collison, a civilised and gentlemanly type who, despite his charm and urbanity, is reluctant to climb the promotion ladder which is presented to him. Detective Sergeant Karen Willis is, likewise, of finishing school material, but also a very good copper with – as we are often reminded – legs to die for. She is in love, but not exclusively, with Detective Inspector Bob Metcalfe, a decent sort with a heart of gold. If he were operating back in the Bulldog Drummond era he would certainly have a lantern jaw and blue eyes that could be steely, or twinkle with kindness as circumstances dictate. Collison, Metcalfe, Willis and Collins have an ever lengthening list of questions to be answered. Why was Ann Durham brandishing a bottle of cyanide as she presided over one of the convention panels? Who actually wrote her most popular – and best selling – series of novels? Fraser-Sampson (right) spins a beautiful yarn here, with regular nods to The Golden Age during a convincing account of modern police procedure. Not only is the crime eventually solved, but he provides us with a delightful solution to the Willis – Metcalfe – Collins love triangle.

Collison, Metcalfe, Willis and Collins have an ever lengthening list of questions to be answered. Why was Ann Durham brandishing a bottle of cyanide as she presided over one of the convention panels? Who actually wrote her most popular – and best selling – series of novels? Fraser-Sampson (right) spins a beautiful yarn here, with regular nods to The Golden Age during a convincing account of modern police procedure. Not only is the crime eventually solved, but he provides us with a delightful solution to the Willis – Metcalfe – Collins love triangle.