The novel is subtitled The Memoirs of Inspector Frank Grasby, and Denzil Meyrick (left) employs the reliable plot-opener of someone in our time inheriting a wooden crate containing the papers of a long-dead police officer, and exploring what was committed to paper. Will crime writers in a hundred years hence have their characters discovering a forgotten folder in the corner of someone’s hard drive? I doubt it – it won’t be anywhere near as much fun.

The novel is subtitled The Memoirs of Inspector Frank Grasby, and Denzil Meyrick (left) employs the reliable plot-opener of someone in our time inheriting a wooden crate containing the papers of a long-dead police officer, and exploring what was committed to paper. Will crime writers in a hundred years hence have their characters discovering a forgotten folder in the corner of someone’s hard drive? I doubt it – it won’t be anywhere near as much fun.

We are in December 1952, although the book starts with an intriguing police report from three years earlier, the significance of which becomes apparent later. Frank Grasby is in his late thirties, saw one or two bad things during his army service, but is now with Yorkshire police, based in York. He is a good copper, albeit with a weakness for the horses, but has made one or two recent blunders for which his punishment is to be sent of the remote village of Elderby, perched up on the North Yorkshire moors. Ostensibly he is there to investigate some farm thefts, but the Chief Constable just wants him out of harm’s way – and the public eye – for a month or two.

Meyrick unashamedly borrows a few ideas from elsewhere. Rather like Lord Peter Wimsey’s car getting stuck in the snow at the beginning of The Nine Tailors, Grasby’s battered police Austin A30 gives up the ghost just short of the village as the snow swirls down, and he has to make the rest of the journey on foot. In Elderby he finds, in no particular order:

♣ A pub called The Hanging Beggar.

♣ Police Sergeant Bleakly – in charge of the local nick, but afflicted with narcolepsy due to his grueling time with the Chindits in Burma.

♣ A delightful American criminology student called Daisy Dean.

♣ A bumptious nouveau-riche ‘Lord of the Manor’ called Damnish (a former tradesman from Leeds, ennobled for his support of the government).

♣ A strange woman called Mrs Gaunt, with whom Grasby and Daisy lodge. Mrs G has a pet raven that sits on her shoulder, and seems to have a mysterious connection to Grasby’s father, an elderly clergyman.

The first corpse enters neither stage right nor left, but rather stage above, when Grasby inadvertently solves Lord Damnish’s smoky fireplace by dislodging an obstruction – a recently deceased male corpse. Next, the American husband of the local GP is found dead in the churchyard. Chuck Starr was a journalist embedded with the Allied forces on D-Day, was appalled by what he saw, and has been writing an exposé on military incompetence. His manuscript – yes, you guessed it – has gone missing.

The more Grasby tugs and frets away at a series of loose ends, the more the fabric of Elderby – as a jolly bucolic paradise inhabited by a few harmless eccentrics – begins to unravel and our man finds himself in the middle of a potentially catastrophic conspiracy.

Some crime novels lead us to thinking dark thoughts about the human condition, while others delight us with their ingenuity, humour and turns of phrase. This is definitely in the latter category but, amidst the entertainment, Meyrick reminds us that war leaves mental scars that can be much slower to heal than their physical counterparts. He takes the threads of familiar and comfortable crime fiction tropes, and weaves a Christmas mystery in a snowy village, but with the shadows of uneasy post-war international alliances darkening the fabric. Murder at Holly House is beautifully written, full of sharp humour, but it is also a revealing portrait of the political tensions rife in 1950s Britain. It is published by Bantam and is available now.

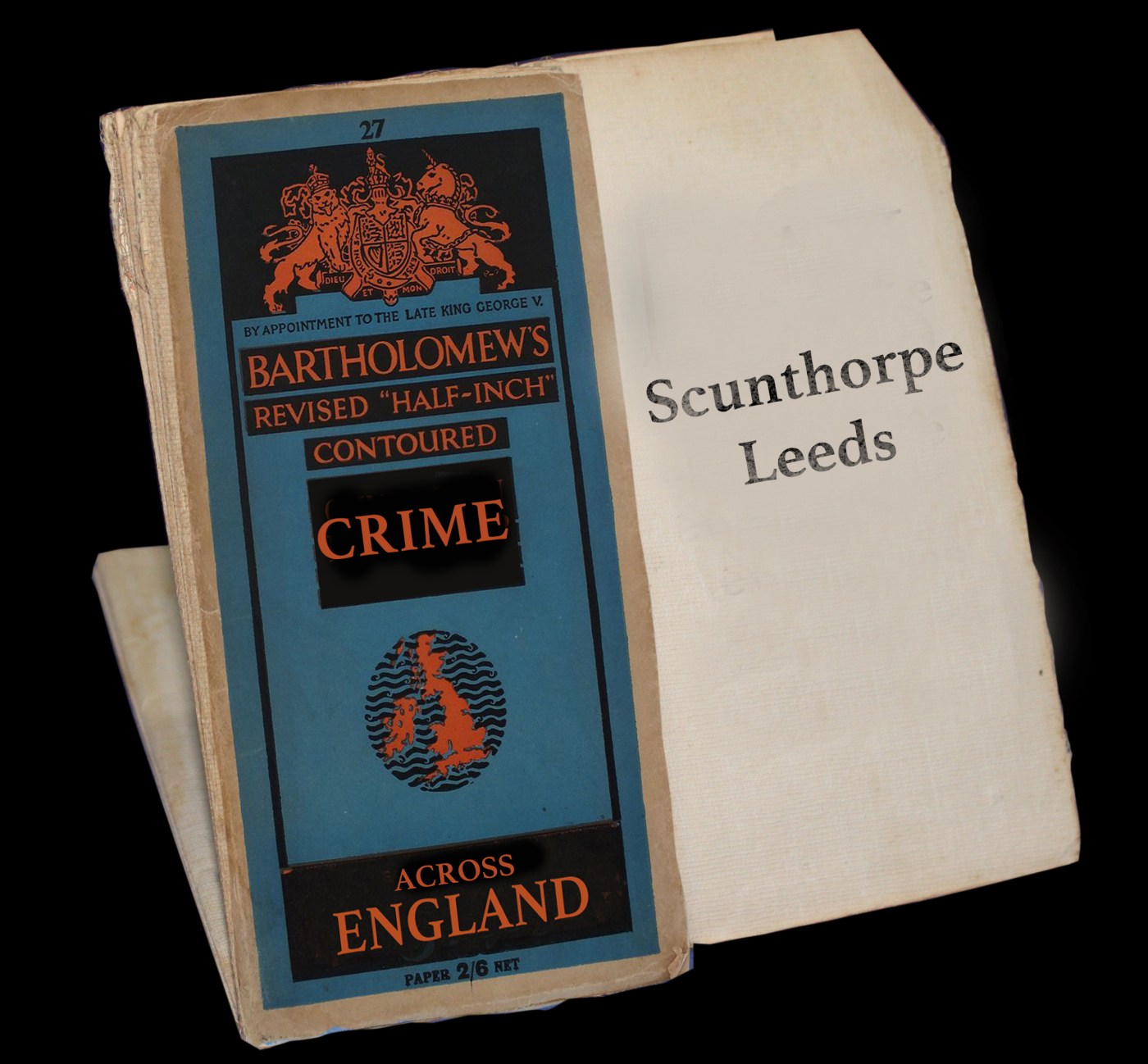

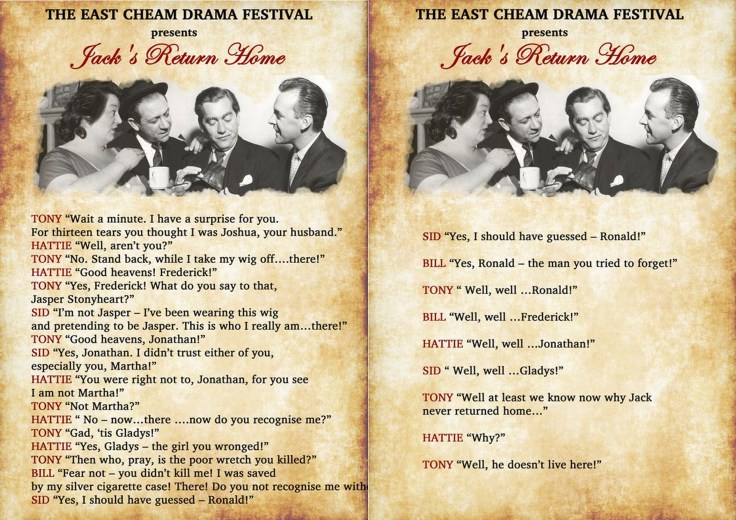

A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians.

A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians. the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.