I recently reviewed The Meadows of Murder by Paul Doherty, set in 14th century London, during the eventful reign of Richard II. Here, we are in York, but slightly earlier. Richard, still not a teenager, is just months into his kingship, and the Goldsmiths of York have, at their own expense, fashioned a miniature golden lion, which is to be presented to the young monarch as a token of allegiance. When the immensely valuable artifact is stolen on the eve of its being carried to London, former Captain of Archers and spymaster for the Archbishop of York, Owen Archer, is called to investigate.

Archer’s wife Lucie is an apothecary and herbalist, and while she and the children are out gathering herbs, they find a corpse in the river. He is naked, and the local fauna have taken his eyes. But who is he, and is he connected with the theft? Following enquiries it seems that the dead man has been noticed in the city over the previous few weeks, but only gave his name as Walter. Central to the search for the stolen lion is another man at arms, Martin Wirthir. The Flemish former soldier and mercenary lives with the Archer family, and is a veteran of many campaigns. He is, however weakened by ill health and injury and, like Tennyson’s Ulysses:

“We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

Walter’s clothes are eventually discovered. Cunningly sewn into their seams are documents that reveal he was Walter Bolton, a spy working for Sir John Neville, Baron of Raby, a powerful soldier and politician, but a man currently out of favour with John of Gaunt. The next corpse to be found is that of Costen van Peelt, another Fleming, and a man suspecting of using his talent – he was a gifted artist – to spy on merchants and politicians across the city. He did not die easily. Archer suspects the brutal torture that preceded his death was an attempt to force him to reveal his many secrets, and the men who were employing to gather them.

Embedded in the heart of this novel is York’s Guild of Goldsmiths. We have nothing today which exactly replicates the Guild system. Guilds were groups of craftsmen and merchants who grouped together for – in theory – mutual protection and benefit. They often wielded more local power than the church and royal functionaries such as Sheriffs and Castellans. Here, discontent rumbles within the ranks of the city’s Goldsmiths. Petty jealousies and professional rivalries can be destructive, but can they lead to murder?

Archer learns that Walter Bolton was not only working for Sir John Neville, but was his illegitimate son. Bastard though he was, Bolton was of Neville’s blood, and the Baron wants answers.

On a geographical note, we would do well to remember the vital part the River Ouse played in York’s history. Now mostly a tourist feature (but still a potent flood risk) the Ouse linked York, via the Humber, to international trade and in this case, the risk of piracy.

Historical crime fiction that is set in eras prior to the mid 19thC is a strange beast, in some ways. The authors – and they are many, and often distinguished – clothe their investigators with a mantle that we know can only have existed in modern times, such as the obvious trappings of interviewing suspects, crime scene investigation, identity parades, the search for motives and the presence or absence of alibis. Did investigators in the 14thC operate like this? We have no evidence to suggest that they did, but it matters not. A Lion’s Ransom is a cracking read and totally engaging. It was published by Severn House on 6th January.

Leigh Russell (right) studied literature at university, and spent four years immersed in books. After that,she became a teacher, a career that enabled her to share her enthusiasm for books with teenagers. For years, she read other people’s books

Leigh Russell (right) studied literature at university, and spent four years immersed in books. After that,she became a teacher, a career that enabled her to share her enthusiasm for books with teenagers. For years, she read other people’s books

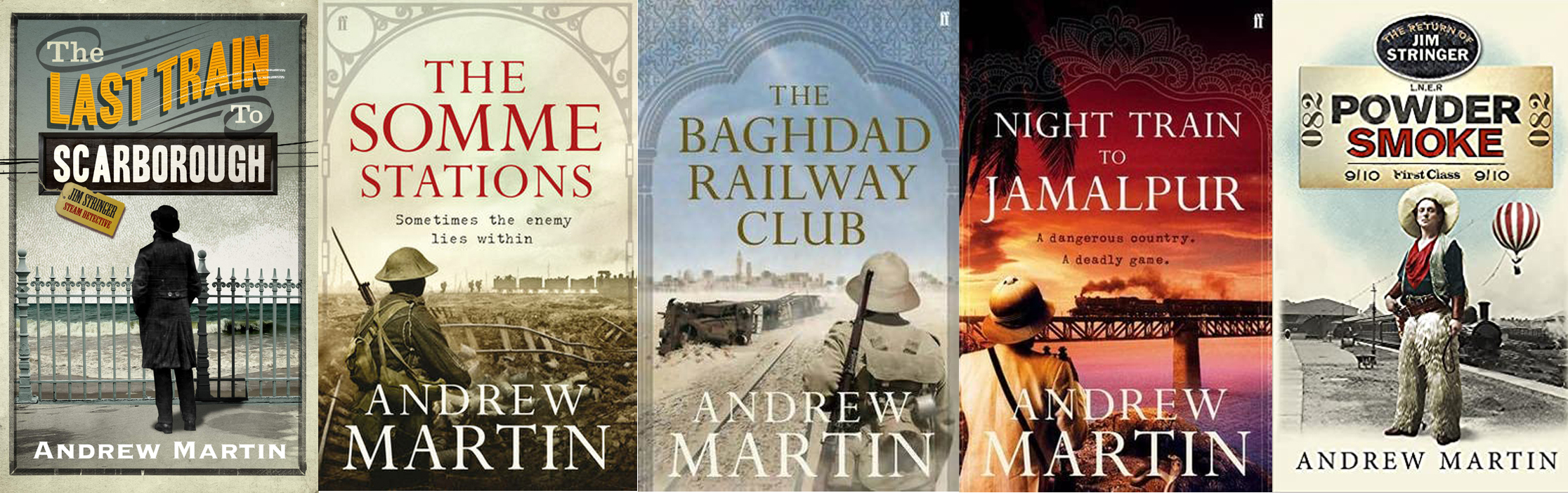

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants. Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.