It is April 1945, and we are in Paris. The fighting has long since moved east, but the consequences of the previous four years are very evident. Charles de Gaulle has marched at the head of his victory parade, convincing some (but not all) that he had liberated France entirely on his own. Across the country, collaborators are being executed, and the women who consorted too freely with Germans are being roughly dealt with. In the gaol at Fresnes are several women who have been liberated from Ravensbruck. They all claim to be victims of the Nazis, but are some of them not who they say they are?

Frederick Rowlands has been brought to Paris by Iris Barnes, an MI6 officer, to confirm – or refute – the identity of a woman he once knew in the days before he lost his sight. He meets Clara Metzner. She is skin and bone, after her incarceration in Ravensbruck, and he is uncertain. The next day, she is found dead in her cell, apparently haven taken her own life.

Fictional detectives seem to be perfectly able to do their jobs despite various physical and mental conditions which might be regarded as disabilities. Nero Wolfe was too obese to leave his apartment, Lincoln Rhyme is quadriplegic, Fiona Griffiths has Cotard’s syndrome, while George Cross is autistic. Christina Koning’s Frederick Rowlands isn’t the first blind detective, of course, as Ernest Bramah’s Max Carrados stories entranced readers over a century ago.

The febrile atmosphere and often uneasy ‘peace’ in Paris is vividly described, and we even have some thinly disguised real life characters with walk-on parts, such as Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn, Pablo Picasso, Edith Piaf, Samuel Beckett, Gertrude Stein and Wyndham Lewis.

As Rowlands and Barnes seem to be clutching at straws as they try to identify the girl who was murdered – a shock induced heart failure, according to the autopsy – the plot spins off at a tangent. Lady Celia, a member of the Irish aristocracy, asks Rowlands to trace a young man, Sebastian Gogarty, a former employee, who was last heard of as a POW in Silesia. He agrees, and as he and Major Cochrane, one of Lady Celia’s admirers head off on their search, they drive through a very different France. Paris, largely untouched by street fighting or bombs, is in stark contrast to the countryside further east, devastated by the retreating Germans. Gogarty has been living with a group of Maquis, but he returns to Paris after telling Rowlands and Cochrane about the execution of four female resistance members in his camp.

There is an interlude, tenderly described when, after failing to resolve issues in France, Rowlands returns to England. During the elation of VE Day, he recalls a more sombre occasion.

“He remembered standing in a crowd in Trafalgar Square as large as this one. It had been on Armistice Day, 1919. That had been a silent crowd, all the more impressive because of its silence. There had been no cheers, no flag waving as there was now. When the maroon sounded, the transformation was immediate. The roar of traffic died. All the men removed their hats. Men and women stood with heads bowed, unmoving. For fully two minutes the silence was maintained then and across the country. Everyone and everything stopped. Buses, trains, trams, and horse-drawn vehicles halted. Factories ceased working, as did offices, shops, hospitals and banks. Schools became silent. Court proceedings came to a standstill. Prisoners stood to attention in their cells. Only the sound of a muffled bell tolling the hour of eleven broke the silence.”

Rowlands and his family reconcile themselves to leaving their temporary home in Brighton for their bomb damaged home in London, but there is much work to be done. When not involved in investigations, Rowlands has worked with St Dunstan’s, the charity set up to employ blind veterans. Now, with tens of thousands of able-bodied military people being demobbed, will there still be work for them?

The action reverts to Paris, wth Rowlands returning, accompanied by young Jewish man, Clara Meltzner’s brother. It becomes increasingly obvious that some organisation is determined to prevent the true identity of the young woman murdered in Fresnes gaol being revealed. Rowland’s problem is that, despite the Germans no longer being physically present, everyone is at each other’s throats – the rival Résistance groups, Gaullists, communists, Nazi sympathisers – each has much to lose, and violence has become a way of life.

Christina Koning’s spirited account of a Paris springtime takes in so many evocative locations – Le cimetière du Père-Lachaise, the sinister depths of the Catacombs, the newly bustling shops fragrant with fresh baked bread and ripe fromage – that we are transported into another world. Murder in Paris will be published by Allison & Busby on 20th November.

The real threat to Graham comes not from the nightclub man but from an elderly archaeologist called Haller, whose long winded monologues about Sumerian funerary rites have made meal times such a bore for the other passengers. Haller is, in fact, a Nazi agent called Moeller, who has been trying – to use chess metaphor – to wipe Graham’s knight off the board for several weeks. This is one of those novels, all too easily parodied, where no-one is who they claim to be. It is from what was, in some ways, a simpler age, where storytellers just told the story, with no ‘special effects’ like multiple time frames and constant changes of narrator.

The real threat to Graham comes not from the nightclub man but from an elderly archaeologist called Haller, whose long winded monologues about Sumerian funerary rites have made meal times such a bore for the other passengers. Haller is, in fact, a Nazi agent called Moeller, who has been trying – to use chess metaphor – to wipe Graham’s knight off the board for several weeks. This is one of those novels, all too easily parodied, where no-one is who they claim to be. It is from what was, in some ways, a simpler age, where storytellers just told the story, with no ‘special effects’ like multiple time frames and constant changes of narrator.

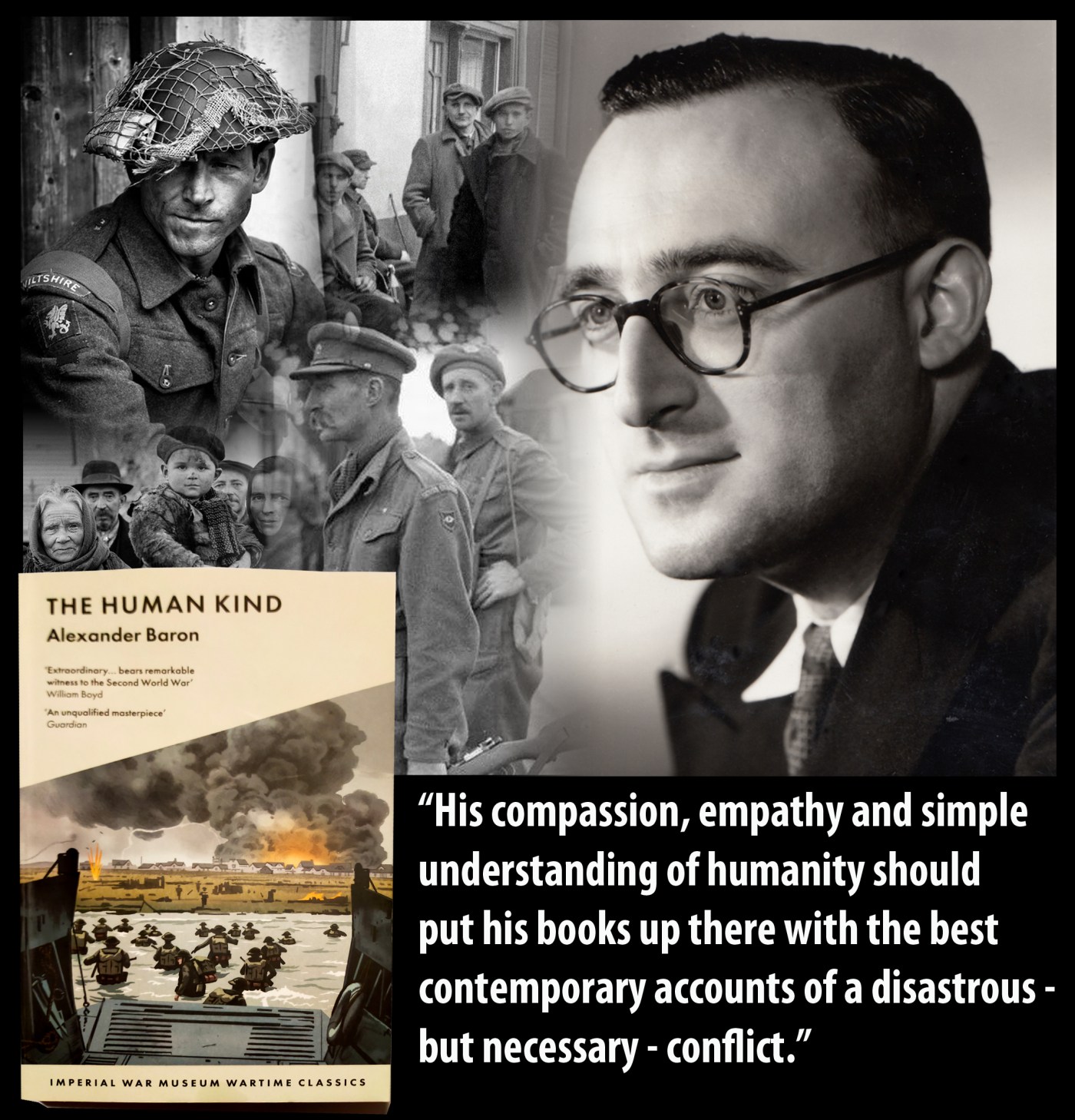

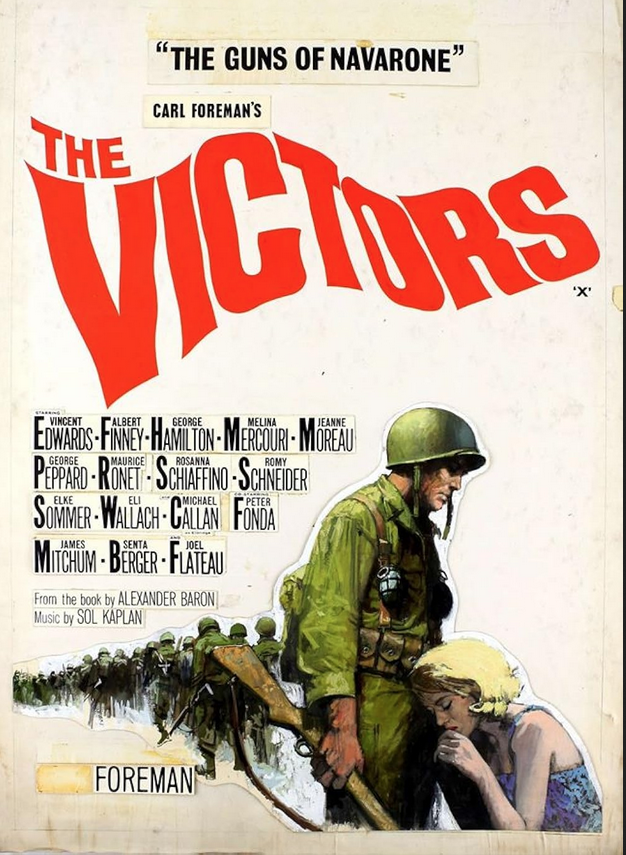

There is black humour in some of the stories, as well as a dark awareness of sexuality. In Chicolino, the soldiers in Baron’s platoon ‘adopt’ a homeless Sicilian boy, just into his teens. They share rations with him and treat him kindly, but are shocked to the core when he assumes that they will want to have sex with him in return for their kindness. He would have been quite happy to oblige, and is hurt and humiliated by their rejection. In The Indian, Baron retells the story from There’s No Home of how Sergeant Craddock comes to sleep with the beautiful Graziela. It is the appearance of a drunk but harmless Indian soldier that brings them into each other’s arms. Readers who, like me, are long in the tooth, will remember watching a 1963 movie called The Victors, directed by Carl Foreman. Alexander Baron was the screenwriter, and the story Everybody Loves a Dog, which relates the unfortunate consequences of a friendless and inarticulate Yorkshire soldier befriending a stray dog, was one of many memorable scenes in the film.

There is black humour in some of the stories, as well as a dark awareness of sexuality. In Chicolino, the soldiers in Baron’s platoon ‘adopt’ a homeless Sicilian boy, just into his teens. They share rations with him and treat him kindly, but are shocked to the core when he assumes that they will want to have sex with him in return for their kindness. He would have been quite happy to oblige, and is hurt and humiliated by their rejection. In The Indian, Baron retells the story from There’s No Home of how Sergeant Craddock comes to sleep with the beautiful Graziela. It is the appearance of a drunk but harmless Indian soldier that brings them into each other’s arms. Readers who, like me, are long in the tooth, will remember watching a 1963 movie called The Victors, directed by Carl Foreman. Alexander Baron was the screenwriter, and the story Everybody Loves a Dog, which relates the unfortunate consequences of a friendless and inarticulate Yorkshire soldier befriending a stray dog, was one of many memorable scenes in the film.