I live in what could be called Cromwell Country. Oliver’s former house in nearby Ely is a tourist attraction, and he is well commemorated in Huntingdon. Was he a Great Englishman? He was certainly an excellent military commander and a successful politician, but I find him hard to warm to. This novel takes us back to the England of 1650. The Civil Wars were over, the King was dead, but the peace was deeply uneasy.

The political situation in 1650 was complex. The country was ruled by the Council of State, a group of forty or so senior politicians who held supreme executive power. It would be another three years before Oliver Cromwell became Head of State, styling himself as Lord Protector. The most significant former Royalists were businessmen and merchants. Their riches and commercial acumen were essential for the country to regain some form of equilibrium after the turmoil of the war years irrespective of their having backed the losing side.

James Archer, a native of Newcastle, is something of a contradiction. He made himself locally notorious by breaking away from his Royalist roots and signing up to fight for Parliament. Although still in his twenties, he has seen – and participated in – great violence, including Cromwell’s barbaric campaign in Ireland. He is sent back to his home town by the Council of State, ostensibly to check that the former King’s men who ran the vital mining and shipping of coal were playing by the rules.

Archer’s subsidiary mission is to investigate the findings of the now infamous Newcastle Witch trials, which took place in 1649 and 1650. The deaths of these women are only of procedural interest to the Council, but Archer certainly has a dog in the fight, as his sister Meg was one of the accused.

What made me distinctly uncomfortable in Bergin’s narrative is his reminder that a society dominated and swayed by hellfire preaching and scriptural quotes is a deeply unstable one. Archer observes the Newcastle town-folk, crowded on the benches of St Nicholas Church, quaking as Dr. Jenison, “so skeletally angular that it appeared he was already half way to the grave,” spits out his sectarian venom, and his demeaning view of the place of women in society. Thank goodness we have no places of worship in Britain where this still goes on. Oh, wait….

After a series of violent encounters, Archer becomes the victim of a conspiracy involving the Great and The Good of Newcastle’s commercial and political world, and he resolves to abandon the town, and head north into the countryisde to search for his sister. As the bruised and battered Archer ventures into border country, he notices something.

“…no men were to be seen. The old had died in the hard winters, the young not yet returned from the wars.”

It is in the Teeside village of Norham that Archer finally earns the truth about his sister, and Bergin has created a masterly ironic twist that is worthy of Thomas Hardy. There is so much to admire in this novel, but one or two things stand out. The fight scenes – and there are several – are superbly described, and the reader can almost hear the clash of steel, and smell the sweat and blood of the participants. Bergin’s historical research is immaculate, as befits a Cambridge history graduate, and his portrayal of the dark and foetid alleys of 17th century Newcastle is vivid and memorable. Published by Northodox Press, this fine novel is available now.

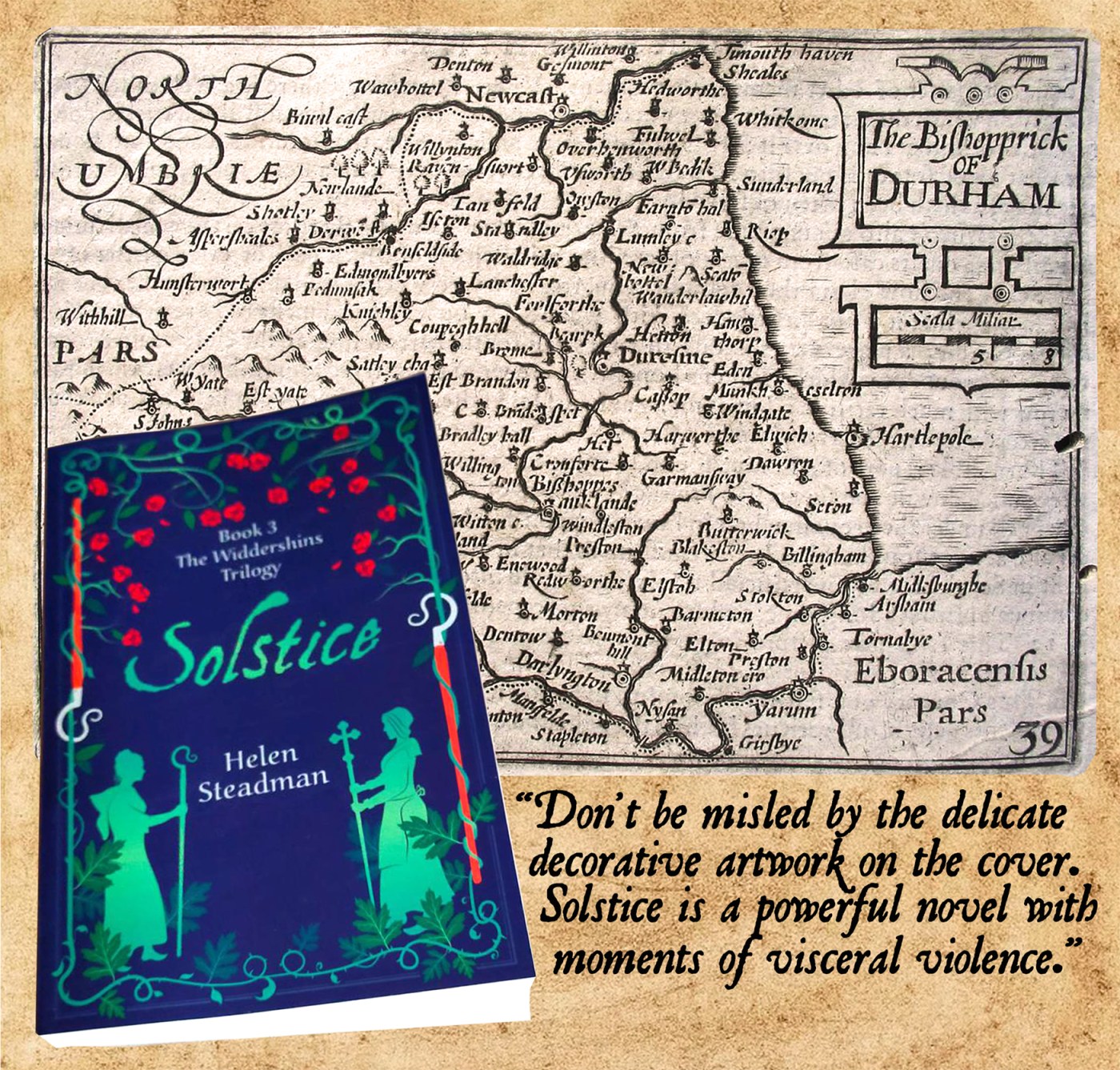

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as