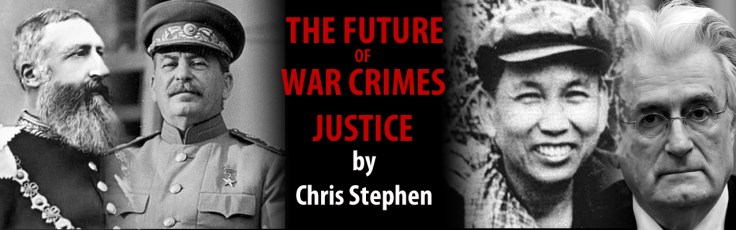

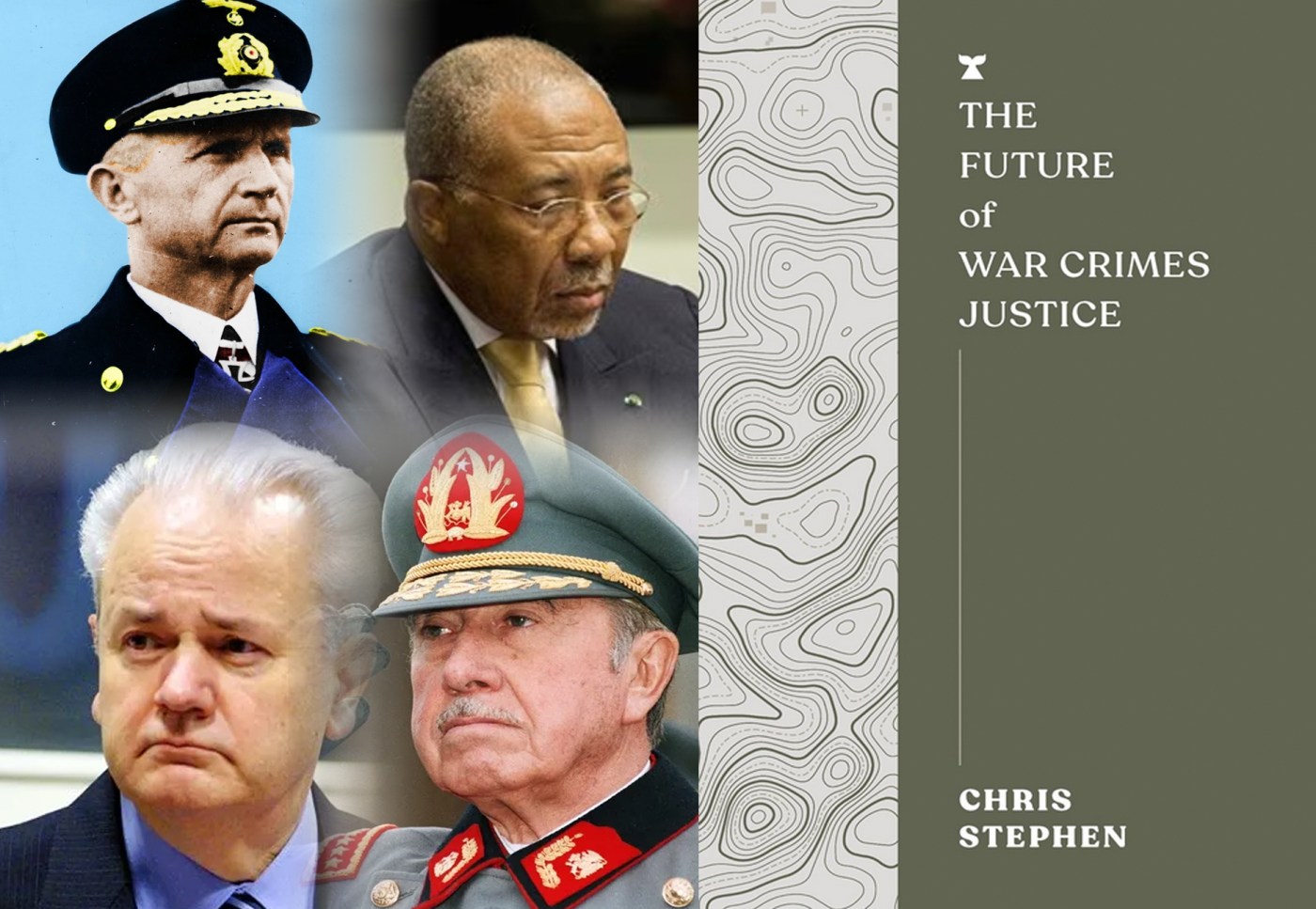

This is what used to be called a monograph, a slim volume devoted to one particular subject. It is a million miles away from Detective Inspectors, international criminals, sleepy villages with an abundance of elderly female amateur sleuths and dark deeds on the gloomy back-streets of Victorian London. However, I do try to balance my reading between novels and non-fiction, and this book repaid my interest. The author, journalist Chris Stephen (left) has reported from nine wars for publications including the Guardian and the New York Times magazine. He is the author of Judgement Day: The Trial of Slobodan Milošević (published by Atlantic Books). Ironically, the Serbian leader avoided becoming only the third former Head of State to be found guilty of war crimes, mainly because he died of a heart attack during his trial. The first was Admiral Karl Dönitz who, for a very brief spell. was leader of Nazi Germany. The second was Charles Taylor the former Liberian leader, at whose trial Naomi Campbell made a brief but bizarre appearance as a witness. This book is part of a new series from Melville House.

This is what used to be called a monograph, a slim volume devoted to one particular subject. It is a million miles away from Detective Inspectors, international criminals, sleepy villages with an abundance of elderly female amateur sleuths and dark deeds on the gloomy back-streets of Victorian London. However, I do try to balance my reading between novels and non-fiction, and this book repaid my interest. The author, journalist Chris Stephen (left) has reported from nine wars for publications including the Guardian and the New York Times magazine. He is the author of Judgement Day: The Trial of Slobodan Milošević (published by Atlantic Books). Ironically, the Serbian leader avoided becoming only the third former Head of State to be found guilty of war crimes, mainly because he died of a heart attack during his trial. The first was Admiral Karl Dönitz who, for a very brief spell. was leader of Nazi Germany. The second was Charles Taylor the former Liberian leader, at whose trial Naomi Campbell made a brief but bizarre appearance as a witness. This book is part of a new series from Melville House.

Stephen looks at war crimes in history, and examines how contemporary justice systems defined them and dealt with them. He mentions Sherman’s ‘March To The Sea’ in 1864, where Sherman’s Union troops devastated civilian Georgia, working on the assumption that denying the enemy infrastructure, provisions and general support was just as effective as blowing them apart with shot and shell.

The point is well made that there are two distinctive kinds of war crimes – those committed by military leaders and those committed on behalf of multinational companies, usually in Africa, in search of precious raw materials. Perhaps unique is the abysmal Leopold II of Belgium who, while also being head of state, was determined to strip the Congo of all its precious resources.

“Arthur Conan Doyle paused his Sherlock Holmes novels to pen an angry call to arms, “The Crime of The Congo.” He wrote:

“The crime which has been wrought in the Congo Lands by King Leopold of Belgium and his followers is the greatest which has ever been known in human animals.

More evidence of the horrors emerged in the photographs taken by British missionary Alice Seely Harris. One picture, re-printed in Europe and America, showed a farmer kneeling in front of the tiny severed hands of his five year old daughter. She had been mutilated by soldiers of the Anglo Belgian Rubber Company.”

For what it’s worth, Leopold is regularly cited in the top ten of the world’s greatest mass murderers alongside fellow luminaries such as Hitler, Stalin, and Pol Pot.

The International Criminal Court, which is central to the book, was established as recently as 2002, and has a chequered history. It is recognised by some countries, but only in so far as its work is not prejudicial to that country’s interest. It is not part of the United Nations and has a rather nebulous authority. Its physical base is in The Hague in the Netherlands.

Because of its unique international position in terms of power and influence, America is an enigma, as Stephen recognises.

“No country agonises over war crimes justice like the the United States. Possibly this is linked to how the USA was formed. Most countries are simply gatherings of a national group. Not America. It was founded on an ideal. Against that, American exceptionalism is the strong current across its political spectrum. The USA’s political class manages to be both internationalist and isolationist at the same time. Leader of the free world, yet also apart from it.”

Stephen’s recounting of the Pinochet affair is particularly telling. Pinochet was the former ruthless and brutal dictator of Chile. He had been deposed, but in 1998 he felt able to travel to London for medical treatment. Because of his support for Britain during the Falklands conflict it was said that Margaret Thatcher thought, “he was one of us.” Instead the criminal justice system decided to detain Pinochet and for some months it seemed to be a message sent to the wider world that no former dictator was immune from justice. Pinochet’s temporary demise was not brought about by any international action but by Spain, who issued an international arrest warrant for him, because several Spanish citizens had been murdered as a result of his purges. In the end there was a change of government, this time the New Labour vision of Tony Blair and, unwilling to upset trading partners, Britain sent Pinochet home, with the excuse that he was too ill to stand trial. Incidentally, just a few days ago he was back in the news again, as claims have been made that he was responsible for having the poet Pablo Neruda poisoned in 1973.

I imagine this book went to press before the 7th of October 2023. Although Chris Stephen does mention the conflict between Palestinian groups and Israel, it raises an interesting prospect of how the ICC will review the ongoing conflict. Who are the war criminals? The IDF? Or Hamas? Interestingly, as I write this review, South Africa has brought a case to the International Court of Justice, alleging that Israel has committed genocide. The ICJ, of course is quite different from the ICC, in that it is part of the United Nations, and can only examine cases involving countries as opposed to individuals.

The author begins his book with an account of an early atrocity by Russia in the current war in Ukraine. If anything this incident highlights both the need for-and the futility of-the International Criminal Court. Of course, Putin has been declared a war criminal by the ICC but, on the other hand, the likelihood of his ever appearing in front of an ICC court is somewhat less than zero.

Stephen concludes on an optimistic note:

“The great, singular achievement of war crimes trials these thirty years has been to show that the system can work. Not always, and not always well. But it has demonstrated that vague conventions can be turned into workable laws.”

The Future of War Crimes Justice is published by Melville House and is available now.

Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann.

Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels bestride the 20th century, from the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany to the post war period when many countries still sheltered mysterious German gentlemen whose collective past has been, of necessity, reinvented. Gunther is a smart talking, smart thinking policeman who has kept his sanity intact – but his conscience rather less so – by dealing with such elemental forces as Reinhardt Heydrich, Joseph Goebbels, Juan and Evita Peron, and Adolf Eichmann. A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS.

A Man Without Breath (2013) sees Gunther is working for an organisation whose very existence may seem improbable, given the historical context, but Die Wehrmacht Untersuchungsstelle (Wehrmacht Bureau of War Crimes) was set up in 1939 and continued its work until 1945. In 1943, on a mission from the Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, Gunther is sent to Smolensk and entrusted with proving that the thousands of corpses lying frozen beneath the trees of the nearby Katyn Forest are those of Polish army officers and intellectuals murdered by the Russian NKVD, and not those of Jews murdered by the SS. the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.

the German military that Hitler is a dangerous upstart who has already damaged the country beyond repair, and must be stopped. Adrift on a sea of violent corruption, Gunther constantly plays the role of the decent man, but in the end, he follows one theology, and one theology only. If he wakes up the next day with his head firmly attached to his shoulders, and has feeling in his extremities, then he has done the right thing. His conscience has not died, but it is far from well; it competes a whole chorale of competing voices in his head, each wishing to be heard. As he is left helpless by the world of spin and disinformation orchestrated by Dr Goebbels, (right) he must resort to his basic copper’s instincts to protect himself and uncover the truth.