Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

He soon has other things to worry about. A quartet of young armed men robs a city centre jewellers, terrifying the staff by firing a shot into the ceiling. They strike again, but this time with fatal consequences. A bystander tries to intervene, and is shot dead for his pains. Many readers will have been following this excellent series for some time, and will know that tragedy has struck the Harper family. Tom’s wife Annabelle has what we know now as dementia, and requires constant care. Their daughter Mary is a widow. Her husband Len is one of the 72000 men who fought and died on the Somme, but have no known grave, and no memorial excep tfor a name on the Thiepval Memorial to The Missing.. Unlike many widows, however, she has been able to rebuild her life, and now runs a successful secretarial agency. Leeds, however, like so many communities, is no place fit for heroes:

“‘Times are hard.’

“I know,” Harper agreed.

It was there in the bleak faces of the men, the worn-down looks of their wives, the hunger that kept the children thin. The wounded ex-servicemen reduced to begging on the streets. Things hadn’t changed much from when he was young. Britain had won the war but forgotten its own people.”

Nickson’s descriptions of his beloved Leeds are always powerful, but here he describes a city – like many others – reeling from a double blow. As if the carnage of the Great War were not enough, the Gods had another spiteful trick up their sleeves in the shape of Spanish Influenza, which killed 228000 people across the country. Many people are still wearing gauze masks in an attempt to ward off infection.

The hunt for the jewel robbers and Ernest Jackson’s letters continues almost to the end of the book and, as ever, Nickson tells a damn good crime story; for me however, the focus had long since shifted elsewhere. This book is all about Tom and Annabelle Harper. Weather-wise, spring is definitely in the air, as bushes and trees come back to life after the bareness of winter, but there is a distinctly autumnal air about what is happening on the page. Harper is, like Tennyson’s Ulysses, not the man he was.

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will.

As he tries to help at the scene of a crime, he reflects:

“There was nothing he could do to help here; he was just another old man cluttering up the pavement and stopping the inspector from doing his job.”

As for Annabelle, the lovely, brave and vibrant woman of the earlier books, little is left:

“The memories would remain. She’d have them too, but they were tucked away in pockets that were gradually being sewn up. All her past was being stolen from her. And he couldn’t stop the theft.”

This is a magnificent and poignant end to the finest series of historical crime fiction I have ever read. It is published by Severn House and will be available on 5th September. For more about the Tom Harper novels, click this link.

A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians.

A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians. the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

We first met Leeds policeman Tom Harper in Gods of Gold (2014) when he was a young CID officer, and the land was still ruled by Queen Victoria. Now, in The Molten City, Harper is a Superintendent and the Queen is seven years dead. ‘Bertie’ – Edward VII – is King, and England is a different place. Leeds, though, is still a thriving hub of heavy industry, pulsing with the throb of heavy machinery. And it remains grimy, soot blackened and with pockets of degradation and poverty largely ignored by the wealthy middle classes. But there are motor cars on the street, and the police have telephones. Other things are stirring, too. Not all women are content to remain second class citizens, and pressure is being put on politicians to consider giving women the vote. Sometimes this is a peaceful attempt to change things, but other women are prepared to go to greater lengths.

We first met Leeds policeman Tom Harper in Gods of Gold (2014) when he was a young CID officer, and the land was still ruled by Queen Victoria. Now, in The Molten City, Harper is a Superintendent and the Queen is seven years dead. ‘Bertie’ – Edward VII – is King, and England is a different place. Leeds, though, is still a thriving hub of heavy industry, pulsing with the throb of heavy machinery. And it remains grimy, soot blackened and with pockets of degradation and poverty largely ignored by the wealthy middle classes. But there are motor cars on the street, and the police have telephones. Other things are stirring, too. Not all women are content to remain second class citizens, and pressure is being put on politicians to consider giving women the vote. Sometimes this is a peaceful attempt to change things, but other women are prepared to go to greater lengths.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.

Outraged leading articles appear in local newspapers, but someone believes that the sword – or something equally violent – is mightier than the pen, and a homemade bomb destroys a church hall just before Annabelle Harper is due to speak to her supporters. The caretaker is tragically killed by the explosion, and matters go from bad to worse when more bombs are found, and several of the women candidates are threatened.

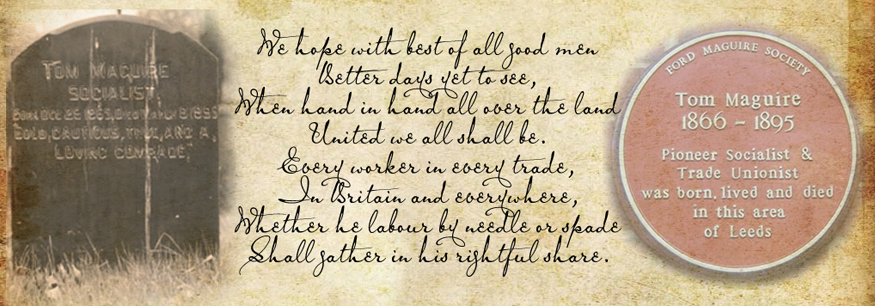

On Copper Street opens in grim fashion, with death and disfigurement. The dead pass in contrasting fashion. Socialist activist Tom Maguire dies in private misery, stricken by pneumonia and unattended by any of the working people whose status and condition he championed. The death of petty crook Henry White is more sudden, extremely violent, but equally final. Having only just been released from the forbidding depths of Armley Gaol, he is found on his bed with a fatal stab wound. If all this isn’t bad enough, two children working in a city bakery have been attacked by a man who threw acid in their faces. The girl will be marked for life, but at least she still has her sight. The last thing the poor lad saw – or ever will see – is the momentary horror of a man throwing acid at him. His sight is irreparably damaged.

On Copper Street opens in grim fashion, with death and disfigurement. The dead pass in contrasting fashion. Socialist activist Tom Maguire dies in private misery, stricken by pneumonia and unattended by any of the working people whose status and condition he championed. The death of petty crook Henry White is more sudden, extremely violent, but equally final. Having only just been released from the forbidding depths of Armley Gaol, he is found on his bed with a fatal stab wound. If all this isn’t bad enough, two children working in a city bakery have been attacked by a man who threw acid in their faces. The girl will be marked for life, but at least she still has her sight. The last thing the poor lad saw – or ever will see – is the momentary horror of a man throwing acid at him. His sight is irreparably damaged. Nickson is a master story teller. There are no pretensions, no gloomy psychological subtext, no frills, bows, fancies or furbelows. We are not required to wrestle with moral ambiguities, nor are we presented with any philosophical conundrums. This is not to say that the book doesn’t have an edge. I would imagine that Nickson (right) is a good old-fashioned socialist, and he pulls no punches when he describes the appalling way in which workers are treated in late Victorian England, and he makes it abundantly clear what he thinks of the chasm between the haves and the have nots. Don’t be put off by this. Nickson doesn’t preach and neither does he bang the table and browbeat. He recognises that the Leeds of 1895 is what it is – loud, smelly, bustling, full of stark contrasts, yet vibrant and fascinating. Follow this link to read our review of the previous Tom Harper novel,

Nickson is a master story teller. There are no pretensions, no gloomy psychological subtext, no frills, bows, fancies or furbelows. We are not required to wrestle with moral ambiguities, nor are we presented with any philosophical conundrums. This is not to say that the book doesn’t have an edge. I would imagine that Nickson (right) is a good old-fashioned socialist, and he pulls no punches when he describes the appalling way in which workers are treated in late Victorian England, and he makes it abundantly clear what he thinks of the chasm between the haves and the have nots. Don’t be put off by this. Nickson doesn’t preach and neither does he bang the table and browbeat. He recognises that the Leeds of 1895 is what it is – loud, smelly, bustling, full of stark contrasts, yet vibrant and fascinating. Follow this link to read our review of the previous Tom Harper novel,

Two gang bosses, one of Irish heritage and the other local, are engaged in a tense truce. They will hold off attacking each other while Harper and his fellow officers track down the mysterious copper-headed man who appears to be connected to the deaths. Time is running out, however, and there is an even more calamitous threat hanging over the heads of the police. The powers-that-be want answers, and as Harper runs around in ever decreasing circles, he is told that if he doesn’t find the killer, then men from Scotland Yard will travel north and take over the case. This, for Harper and his boss Superintendent Kendall, will be the ultimate disgrace.

Two gang bosses, one of Irish heritage and the other local, are engaged in a tense truce. They will hold off attacking each other while Harper and his fellow officers track down the mysterious copper-headed man who appears to be connected to the deaths. Time is running out, however, and there is an even more calamitous threat hanging over the heads of the police. The powers-that-be want answers, and as Harper runs around in ever decreasing circles, he is told that if he doesn’t find the killer, then men from Scotland Yard will travel north and take over the case. This, for Harper and his boss Superintendent Kendall, will be the ultimate disgrace.