This is a welcome return to the world of Edinburgh copper Tony McLean. He is now Chief Inspector, and to quote, appropriately enough, the Scottish Play, he feels he is dressed in ‘borrow’d robes’. On his desk are small mountains of files, reports, initiatives and consultation documents: beyond the door of the nick are thieves, rapists and murderers. McLean knows where his heart is leading him, and it is out away from his desk and onto the mean streets.

When McLean uses the excuse of a potential clash between rival demonstrators to desert his office, he discovers a corpse abandoned in a derelict cellar. As the technicians and medics swarm round the body it seems obvious that the remains – of a young girl – have been there for some considerable time. When, however, the pathologist is able to take a closer look under the spotlight above the mortuary slab, he comes to the astonishing conclusion that the girl has only been dead for a matter of days, despite her desiccated and leathery skin.

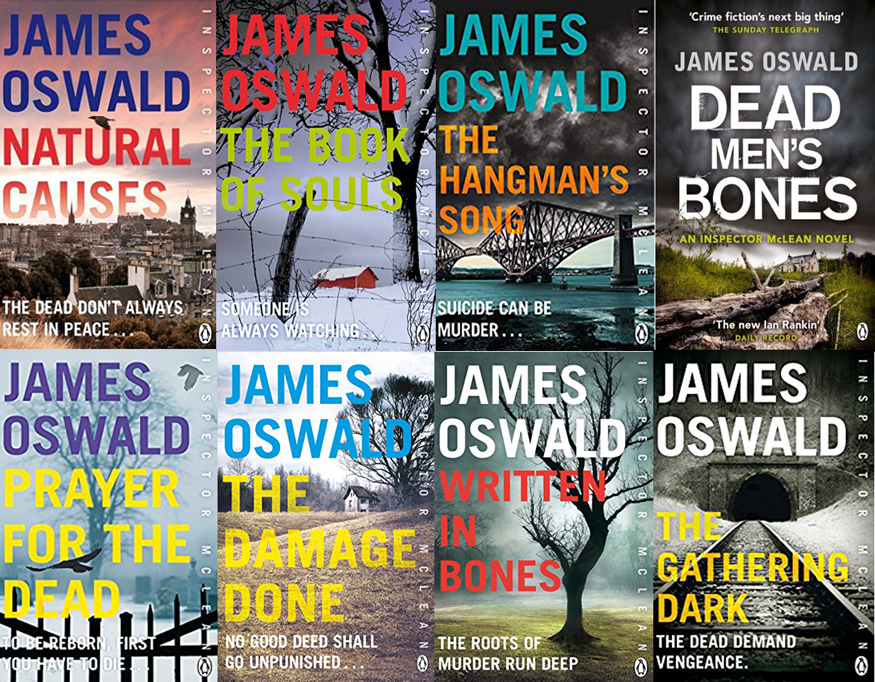

Cold As The Grave is the ninth novel in the Tony McLean series, but fine writers – and Oswald is up there with the very best – make sure that it is never too late to come to the party. For anyone new to the series, McLean is something of an individual. Due to an inheritance, he is exceedingly wealthy, but has a modest lifestyle and chooses to remain a police officer. He has a long-standing ‘significant other’ in Emma Baird, but the previous novel, The Gathering Dark, (click to read the review) ended with her having a disastrous miscarriage. McLean is a fine detective, but he is blessed, or perhaps cursed, with an awareness of the supernatural. The two characters in the books who operate in this sphere are Madame Rose, a bizarre but benign transvestite clairvoyant, and the considerably more sinister Mrs Saifre. She is, on the surface, merely a very rich and influential owner of newspapers and media outlets, but McLean senses that there is something existentially evil and elemental behind her smooth corporate image.

Cold As The Grave is the ninth novel in the Tony McLean series, but fine writers – and Oswald is up there with the very best – make sure that it is never too late to come to the party. For anyone new to the series, McLean is something of an individual. Due to an inheritance, he is exceedingly wealthy, but has a modest lifestyle and chooses to remain a police officer. He has a long-standing ‘significant other’ in Emma Baird, but the previous novel, The Gathering Dark, (click to read the review) ended with her having a disastrous miscarriage. McLean is a fine detective, but he is blessed, or perhaps cursed, with an awareness of the supernatural. The two characters in the books who operate in this sphere are Madame Rose, a bizarre but benign transvestite clairvoyant, and the considerably more sinister Mrs Saifre. She is, on the surface, merely a very rich and influential owner of newspapers and media outlets, but McLean senses that there is something existentially evil and elemental behind her smooth corporate image.

Back in Cold As The Grave, more bodies are found, each apparently mummified in the same way as the poor child found in the tenement cellar. McLean makes an important connection between the deaths and the rising tide of people trafficking which has hit the city. Girls and young women from the war zones of the Middle East are being brought in and, at best, set to work for a pittance in local factories but, at worst, forced into prostitution.

With his bosses exasperated at the amount of time he is spending away from his paper shuffling duties, McLean’s investigation reaches a crucial fork in the road. To the left is the grim possibility that someone at the heart of the trafficking gang is using some kind of deadly serum, derived from snake venom, to carry out murders and threaten other victims: to the right, however improbable, is the presence of some kind of evil djinn reincarnated from Aramaic legend and folklore. McLean knows that following the road to the right will lead only to ridicule by both his superior officers and those who work for him, but he has learned to trust his instincts, even if they terrify him.

Does McLean follow his head or his heart? The road to the left or the right? Cold As The Grave is a brilliant police procedural, but there is more – so much more – to it. For those who love topographical atmosphere Oswald (right) recreates a wintry Edinburgh that makes you want to turn up the central heating by a couple of notches; for readers drawn by suggestions of the supernatural there is enough here to induce a shiver or three, while making sure the bedroom light remains on while you sleep. The sheer decency and common humanity of Tony McLean – and the finely detailed portraits of the people he works with – will satisfy the reader who demands authentic and credible characterisation. Cold As The Grave is published by Wildfire/Headline and will be out on 7th February.

Does McLean follow his head or his heart? The road to the left or the right? Cold As The Grave is a brilliant police procedural, but there is more – so much more – to it. For those who love topographical atmosphere Oswald (right) recreates a wintry Edinburgh that makes you want to turn up the central heating by a couple of notches; for readers drawn by suggestions of the supernatural there is enough here to induce a shiver or three, while making sure the bedroom light remains on while you sleep. The sheer decency and common humanity of Tony McLean – and the finely detailed portraits of the people he works with – will satisfy the reader who demands authentic and credible characterisation. Cold As The Grave is published by Wildfire/Headline and will be out on 7th February.

Thus begins another case for Professor Matt Hunter, a university lecturer in religion and belief. He has previously helped the police in cases which involve sacred or supernatural matters (see the end of this review) and he is called in when it becomes clear that the wielder of the axe was none other than the teenage son of the Reverend David East, and that the boy was under the spell of a cult of deviant Christians whose central belief is that God The Father is a brutal tyrant who murdered his only son. They are also convinced that all other humans but them are ‘Hollows’ with evil in their eyes. Consequently, they shun all contact with the outside world, and live in a remote farmhouse, deep in the hills at the end of a rutted farm track.

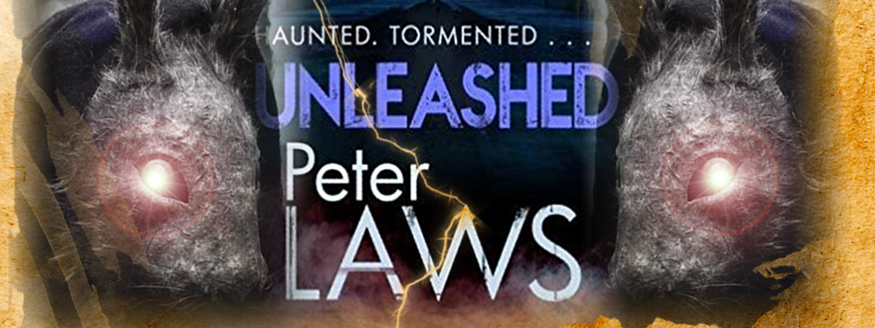

Thus begins another case for Professor Matt Hunter, a university lecturer in religion and belief. He has previously helped the police in cases which involve sacred or supernatural matters (see the end of this review) and he is called in when it becomes clear that the wielder of the axe was none other than the teenage son of the Reverend David East, and that the boy was under the spell of a cult of deviant Christians whose central belief is that God The Father is a brutal tyrant who murdered his only son. They are also convinced that all other humans but them are ‘Hollows’ with evil in their eyes. Consequently, they shun all contact with the outside world, and live in a remote farmhouse, deep in the hills at the end of a rutted farm track. One of the most intriguing aspects of the Matt Hunter books is the relationship between the fictional former man of God and the very real and present minister in the Baptist church, the Reverend Peter Laws himself . We get a very vivid and convincing account of how Hunter has lost his faith, but also the many facets of that belief that he has come to see as inconsistent, illogical, or just plain barbaric. It suggests that Laws has identified these doubts in his own mind but, presumably, answered them. In these days of CGI nothing is impossible, so a live debate between Reverend Laws and Professor Hunter would be something to behold.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Matt Hunter books is the relationship between the fictional former man of God and the very real and present minister in the Baptist church, the Reverend Peter Laws himself . We get a very vivid and convincing account of how Hunter has lost his faith, but also the many facets of that belief that he has come to see as inconsistent, illogical, or just plain barbaric. It suggests that Laws has identified these doubts in his own mind but, presumably, answered them. In these days of CGI nothing is impossible, so a live debate between Reverend Laws and Professor Hunter would be something to behold.

In the dark woods of Maine a tree gives up the ghost and topples to the ground. As its roots spring free of the cold earth a makeshift tomb is revealed. The occupant was a young woman. When the girl – for she was little more than that – is discovered, the police and the medical services enact their time-honoured rituals and discover that she died of natural causes not long after giving birth. But where is the child she bore? And why was a Star of David carved on the trunk of an adjacent tree? Portland lawyer Moxie Castin is not a particularly devout Jew, but he fears that the ancient symbol may signify something damaging, and he hires PI Charlie Parker to shadow the police enquiry and investigate the carving – and the melancholy discovery beneath it.

In the dark woods of Maine a tree gives up the ghost and topples to the ground. As its roots spring free of the cold earth a makeshift tomb is revealed. The occupant was a young woman. When the girl – for she was little more than that – is discovered, the police and the medical services enact their time-honoured rituals and discover that she died of natural causes not long after giving birth. But where is the child she bore? And why was a Star of David carved on the trunk of an adjacent tree? Portland lawyer Moxie Castin is not a particularly devout Jew, but he fears that the ancient symbol may signify something damaging, and he hires PI Charlie Parker to shadow the police enquiry and investigate the carving – and the melancholy discovery beneath it. In another life John Connolly would have been a poet. His prose is sonorous and powerful, and his insights into the world of Charie Parker – both the everyday things he sees with his waking eyes and the dark landscape of his dreams – are vivid and sometimes painful. Connolly’s villains – and there have been many during the course of the Charlie Parker series – are not just bad guys. They do dreadful things, certainly, but they even smell of the decaying depths of hell, and they often have powers that even a gunshot to the head from a .38 Special can hardly dent.

In another life John Connolly would have been a poet. His prose is sonorous and powerful, and his insights into the world of Charie Parker – both the everyday things he sees with his waking eyes and the dark landscape of his dreams – are vivid and sometimes painful. Connolly’s villains – and there have been many during the course of the Charlie Parker series – are not just bad guys. They do dreadful things, certainly, but they even smell of the decaying depths of hell, and they often have powers that even a gunshot to the head from a .38 Special can hardly dent.

I should add, at this point, that James Oswald (left) is not your regulation writer of crime fiction novels. He has a rather demanding ‘day job’, which is running a 350 acre livestock farm in North East Fife, where he raises pedigree Highland Cattle and New Zealand Romney Sheep. His entertaining Twitter feed is, therefore, just as likely to contain details of ‘All Creatures Great and Small’ obstetrics as it is to reveal insights into the art of writing great books. But I digress. I don’t know James Oswald well enough to say whether or not he puts anything of himself into the character of Tony McLean, but the scenery and routine of McLean’s life is nothing like that of his creator.

I should add, at this point, that James Oswald (left) is not your regulation writer of crime fiction novels. He has a rather demanding ‘day job’, which is running a 350 acre livestock farm in North East Fife, where he raises pedigree Highland Cattle and New Zealand Romney Sheep. His entertaining Twitter feed is, therefore, just as likely to contain details of ‘All Creatures Great and Small’ obstetrics as it is to reveal insights into the art of writing great books. But I digress. I don’t know James Oswald well enough to say whether or not he puts anything of himself into the character of Tony McLean, but the scenery and routine of McLean’s life is nothing like that of his creator. McLean is going about his daily business when he is witness to a tragedy. A tanker carrying slurry is diverted through central Edinburgh by traffic congestion on the bypass. The driver has a heart attack, and the lorry becomes a weapon of mass destruction as it ploughs into a crowded bus stop. McLean is the first police officer on the scene, and he is immediately aware that whatever the lorry was carrying, it certainly wasn’t harmless – albeit malodorous – sewage waste. People whose bodies have not been shattered by thirty tonnes of hurtling steel are overcome and burned by a terrible toxic sludge which floods from the shattered vehicle.

McLean is going about his daily business when he is witness to a tragedy. A tanker carrying slurry is diverted through central Edinburgh by traffic congestion on the bypass. The driver has a heart attack, and the lorry becomes a weapon of mass destruction as it ploughs into a crowded bus stop. McLean is the first police officer on the scene, and he is immediately aware that whatever the lorry was carrying, it certainly wasn’t harmless – albeit malodorous – sewage waste. People whose bodies have not been shattered by thirty tonnes of hurtling steel are overcome and burned by a terrible toxic sludge which floods from the shattered vehicle.

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

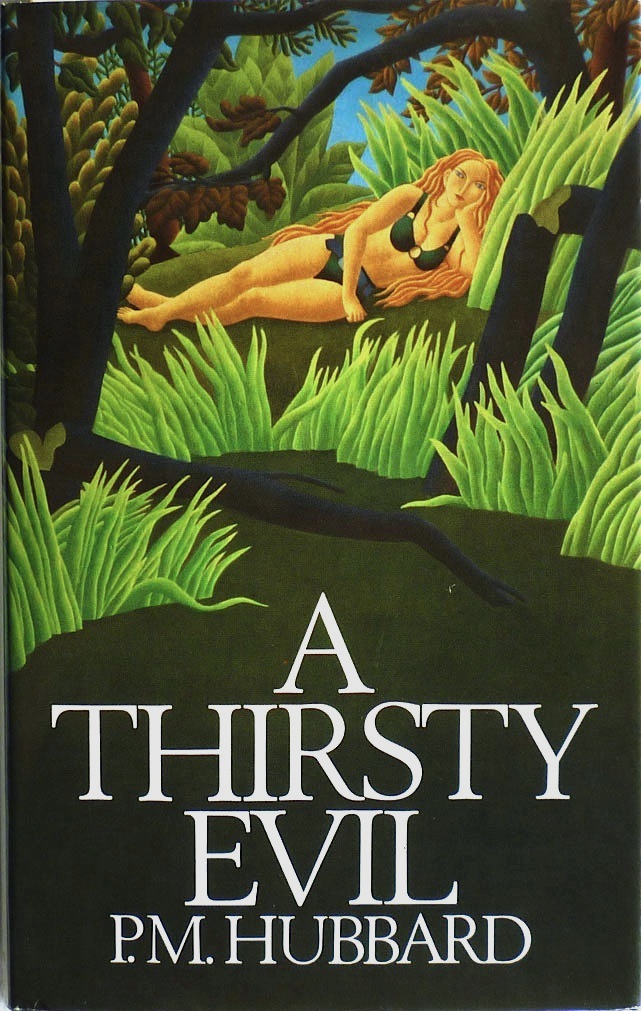

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure.

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure. The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.

The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.

If the South London suburb of Menham could be described as unremarkable, then we might call the down-at-heel terraced houses of Barley Street positively nondescript. Except, that is, for number 29. For a while, the home of Mary Wasson and her daughters became as notorious as 112 Ocean Avenue, Amityville. But the British tabloid press being what it is, there are always new horrors, fresh outrages and riper scandals, and so the focus moved on. The facts, however, were this. After a spell of unexplained poltergeist phenomena turned the house (almost literally) upside down, the body of nine year-old Holly Wasson was found – by her older sister Rachel – hanging from a beam in her bedroom.

If the South London suburb of Menham could be described as unremarkable, then we might call the down-at-heel terraced houses of Barley Street positively nondescript. Except, that is, for number 29. For a while, the home of Mary Wasson and her daughters became as notorious as 112 Ocean Avenue, Amityville. But the British tabloid press being what it is, there are always new horrors, fresh outrages and riper scandals, and so the focus moved on. The facts, however, were this. After a spell of unexplained poltergeist phenomena turned the house (almost literally) upside down, the body of nine year-old Holly Wasson was found – by her older sister Rachel – hanging from a beam in her bedroom. Laws (right) takes a leaf out of the book of the master of atmospheric and haunted landscapes, M R James. The drab suburban topography of Menham comes alive with all manner of dark interventions; we jump as a wayward tree branch scrapes like a dead hand across a gazebo roof; we recoil in fear as a white muslin curtain forms itself into something unspeakable; dead things scuttle and scrabble about in dark corners while, in our peripheral vision, shapes form themselves into dreadful spectres. When we turn our heads, however, there is nothing there but our own imagination.

Laws (right) takes a leaf out of the book of the master of atmospheric and haunted landscapes, M R James. The drab suburban topography of Menham comes alive with all manner of dark interventions; we jump as a wayward tree branch scrapes like a dead hand across a gazebo roof; we recoil in fear as a white muslin curtain forms itself into something unspeakable; dead things scuttle and scrabble about in dark corners while, in our peripheral vision, shapes form themselves into dreadful spectres. When we turn our heads, however, there is nothing there but our own imagination.

In Unleashed, his scepticism is shaken by events at an otherwise unremarkable terraced house in South London where, several years ago, a troubled nine-year-old girl committed suicide in the midst of a troubling sequence of poltergeist phenomena.

In Unleashed, his scepticism is shaken by events at an otherwise unremarkable terraced house in South London where, several years ago, a troubled nine-year-old girl committed suicide in the midst of a troubling sequence of poltergeist phenomena.

Before he had the brainwave which gave us Merrily Watkins in The Wine of Angels (1998), Rickman wrote several standalone novels. The most music-centred one was December (1994). It begins on the evening of Monday 8th December, 1980. For most people of a certain age, that date will be an instant trigger, but Rickman (right) sets us down in a ruined abbey in the remote Welsh hamlet of Ystrad Ddu, which sits at the foot of one of The Black Mountains, Ysgyryd Fawr – more commonly known by its anglicised form The Skirrid. Part of the medieval abbey has been fitted out as a recording studio and, in a cynical act of niche marketing, a record impresario has contracted a folk rock band, The Philosopher’s Stone, to record an album of mystical songs in the haunted building, and he has stipulated that the tracks must be laid down between midnight and dawn.

Before he had the brainwave which gave us Merrily Watkins in The Wine of Angels (1998), Rickman wrote several standalone novels. The most music-centred one was December (1994). It begins on the evening of Monday 8th December, 1980. For most people of a certain age, that date will be an instant trigger, but Rickman (right) sets us down in a ruined abbey in the remote Welsh hamlet of Ystrad Ddu, which sits at the foot of one of The Black Mountains, Ysgyryd Fawr – more commonly known by its anglicised form The Skirrid. Part of the medieval abbey has been fitted out as a recording studio and, in a cynical act of niche marketing, a record impresario has contracted a folk rock band, The Philosopher’s Stone, to record an album of mystical songs in the haunted building, and he has stipulated that the tracks must be laid down between midnight and dawn.

All Of A Winter’s Night is the latest episode in the turbulent career of the Reverend Merrily Watkins. Her philandering husband long since dead in a catastrophic road accident, Merrily has a daughter to raise and a living to make. Her living has a day job and also what she refers to as her ‘night job’. She is Vicar of the Herefordshire village of Ledwardine, but also the diocesan Deliverance Consultant. That lofty term is longhand for what the tabloids might call “exorcist”. If you are new to the series, you could do worse than follow the link to our readers’ guide to

All Of A Winter’s Night is the latest episode in the turbulent career of the Reverend Merrily Watkins. Her philandering husband long since dead in a catastrophic road accident, Merrily has a daughter to raise and a living to make. Her living has a day job and also what she refers to as her ‘night job’. She is Vicar of the Herefordshire village of Ledwardine, but also the diocesan Deliverance Consultant. That lofty term is longhand for what the tabloids might call “exorcist”. If you are new to the series, you could do worse than follow the link to our readers’ guide to