Firstly, I am not going to argue that this book by William Faulkner is a crime novel in the way that Intruder in the Dust, Sanctuary and several others are deeply rooted in crime and the justice system. The only illegal act in the book is when one of the characters, driven crazy by his own demons and recent events, commits arson.

We are in rural Mississippi, in the 1920s. The Bundren family are hard scrabble farmers who eke out a living growing cotton and selling lumber. Anse and Addie Bundren have five children. In order of age they are Cash, Darl, Jewel, Dewey Dell (the only girl) and Vardaman.

It is high summer, and Adddie Bundren is dying. The title of the novel, incidentally, comes from a translation of Homer’s Odyssey.

“As I lay dying, the woman with the dog’s eyes would not close my eyes as I descended into Hades.”

We must assume that Addie has cancer, as she is worn down to skin and bones. Two things here; any medical help is via Dr Peabody who is many miles away (and expensive); secondly, although Anse makes optimistic remarks about seeing his wife up and well again, it is obvious that the family (with the exception of Vardaman) know the truth. In a macabre touch, Cash – a skilled carpenter – is actually making his mother’s coffin outside in the yard just beyond her window. Addie breathes her last, and Anse reveals that he has made a promise to his wife that she will be buried near her own folks in Jefferson, many days away for a cart and mule team. It is from this point that the source of Faulkner’s title becomes apposite.

Stories told by multiple narrators were nothing new, even in the 1930s, but in my reading experience Faulkner is unique in that here, he uses fifteen different pairs of eyes – each given at least one chapter – to describe Addie Bundren’s last journey. We hear from the seven Bundrens including, perhaps from the afterlife, Addie herself. The eight other voices are neighbours and people who observe the fraught progress of Addie’s coffin to Jefferson.

The Bundren’s odyssey is a startling mixture of horror and the blackest of black comedy. Several vivid chapters describe their attempt to get across a river swollen by torrential rain. it is catastrophic, The mules are swept away and killed, Cash has his leg broken but – with great difficulty – Addie’s coffin is saved. The ghoulish comedy centres on the fact that the summer heat is having an unpleasant but inevitable effect on the unembalmed body of Addie Bundren. The people in settlements and homesteads where the cortege rests for the night are, understandably less than impressed, and each evening, as the sun sets, vultures descend from the heavens and perch near the coffin, sensing a meal.

The essence of the book is the skill with which Faulkner uses the journey (perhaps, on one level, an allegory) to describe the Bundren family. Darl has the most to say, and his thoughts reveal a deeply intelligent and perceptive individual, but one whose sensitivity could bring danger – which it does. Cash is stoical, courageous and unselfish, while young Vardaman’s bewilderment at the turn of events leads him to have strange flights of fancy. Seventeen year-old Dewey Dell is conscious of her own sexuality, and has a big secret – she is two months pregnant. Anse is a simple farmer and somewhat overwhelmed by his children. His determination to grant Addie her last wish in death is, perhaps, a result of being unable to bring her much in life.

Which leaves us with Jewel. He is very different from his siblings, possibly because he has a different father. This isn’t revealed until mid way through the novel, but it is significant. His father is Whitfield, a local hellfire preacher. To his half siblings Jewel seems permanently angry, and vexatious. Faulkner only gives Jewel one chapter, which rather confirms that he is not much given to introspection. Two actions show Jewel’s nobility of spirit. Having secretly worked at night for another farmer, he has saved enough money to buy a horse, which sets him apart from the others. When the mules are killed at the river, he allows his precious horse to be traded for a replacement team. In the same incident, when Cash and his precious tools are thrown into the river, with Cash lying badly injured and senseless on the bank, Jewel repeatedly dives into the turbulent water and, one by one, the tools are recovered.

The battered funeral party, minus Darl, whose obsessions have turned into apparent insanity, eventually bury what is left of Addie ‘alongside her own folks’, and it is left to Anse to provide two final moments of mordant humour. Books like Sanctuary and its sequel Requiem for a Nun certainly serve up plentiful reminders of the ‘evil that men do’, but As I Lay Dying is rather different. There is abundant misfortune and weakness, certainly, but apart from the lecherous pharmacist near the end who tries to take advantage of Dewey Dell, there’s little malice, many examples of human kindness, but – above all – an astonishing mixture of poetry, pathos, black humour and narrative skill. As I Lay Dying was first published by Random House in 1931.

I have come to the novels of William Faulkner (left) late in life. Perhaps that is just as well. I am not sure how, as a younger man, I would have dealt with his baleful accounts of one or two truly awful human beings. Having just read Sanctuary, my first reaction is a sense of having been exposed to the very worst of us. The psychotic little gangster Popeye is an embodiment of genuine evil. He is warped both physically and mentally but seems invulnerable, echoing Shakespeare’s description of Julius Caesar ‘

I have come to the novels of William Faulkner (left) late in life. Perhaps that is just as well. I am not sure how, as a younger man, I would have dealt with his baleful accounts of one or two truly awful human beings. Having just read Sanctuary, my first reaction is a sense of having been exposed to the very worst of us. The psychotic little gangster Popeye is an embodiment of genuine evil. He is warped both physically and mentally but seems invulnerable, echoing Shakespeare’s description of Julius Caesar ‘

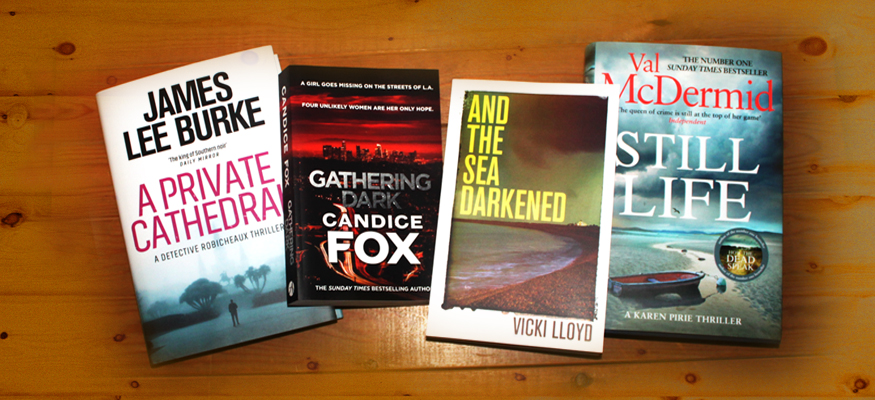

It looks as though the bastards at WordPress have done their worst, and inflicted the ‘new improved’ system on us. Bastards. I rarely swear in print, but this time I have a good excuse.The good news, however, is that I have some lovely new books in my shelf. Full reviews will follow in due course, but here’s a little introduction to each.

It looks as though the bastards at WordPress have done their worst, and inflicted the ‘new improved’ system on us. Bastards. I rarely swear in print, but this time I have a good excuse.The good news, however, is that I have some lovely new books in my shelf. Full reviews will follow in due course, but here’s a little introduction to each.

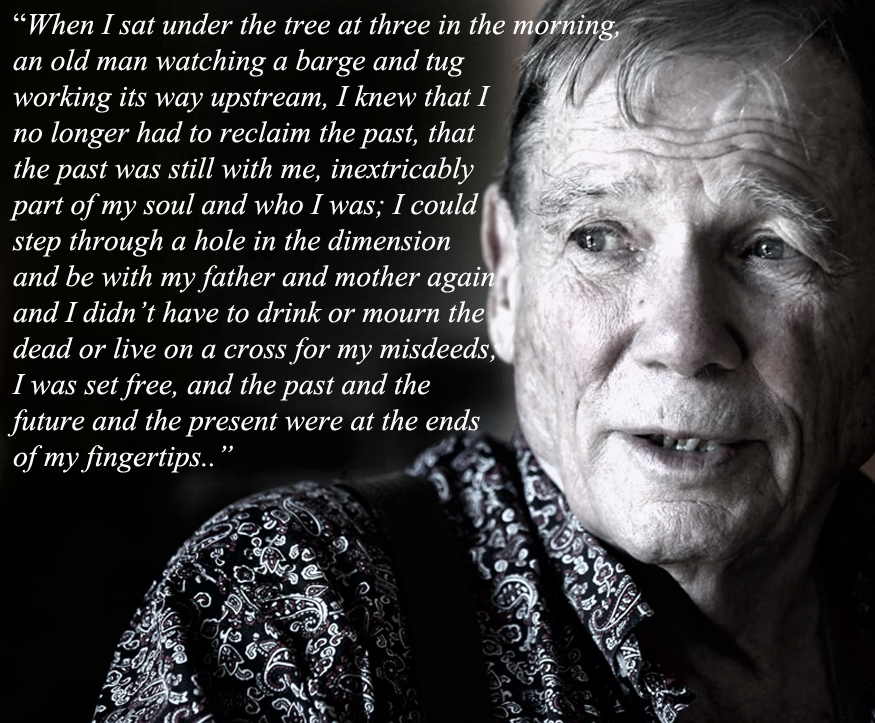

ccasionally I miss out on ARCs and book proofs, and so when I realised the magisterial James Lee Burke had written another Dave Robicheaux novel, and that I was not on the publicist’s mailing list, I went and bought a Kindle version. Just shy of ten quid, but never has a tenner been better spent.

ccasionally I miss out on ARCs and book proofs, and so when I realised the magisterial James Lee Burke had written another Dave Robicheaux novel, and that I was not on the publicist’s mailing list, I went and bought a Kindle version. Just shy of ten quid, but never has a tenner been better spent. To be blunt, JLB is getting on a bit, and one wonders how long he can carry on writing such brilliant books. In the last few novels featuring the ageing New Iberia cop, there has been a definite autumnal feel, and The New Iberia Blues is no exception. Like his creator, Dave Robicheaux is not a young man, but boy, is he ever raging against the dying of the light.

To be blunt, JLB is getting on a bit, and one wonders how long he can carry on writing such brilliant books. In the last few novels featuring the ageing New Iberia cop, there has been a definite autumnal feel, and The New Iberia Blues is no exception. Like his creator, Dave Robicheaux is not a young man, but boy, is he ever raging against the dying of the light. series of apparently ritualised killings baffles the police department, beginning with a young woman strapped to a wooden cross and set adrift in the ocean. This death is just the beginning, and Robicheaux – aided, inevitably, by the elemental force that is Cletus Purcel – struggles to find the killer as the manner of the subsequent deaths exceeds abbatoir levels of brutality. There is no shortage of suspects. A driven movie director deeply in hock to criminal backers, a preening and narcissistic former mercenary, a religious crazy man on the run from Death Row – you pays your money and you takes your choice. We even have the return of the bizarre and deranged contract killer known as Smiley – surely one of the most sinister and damaged killers in all crime fiction. Smiley is described as looking like a shapeless white caterpillar. Horrifically abused as a child, he is happiest when buying ice-creams for children – or killing bad people with Dranol or incinerating them with a flame thrower. Even Robicheaux’s new police partner, the fragrantly named Bailey Ribbons is not beyond suspicion.

series of apparently ritualised killings baffles the police department, beginning with a young woman strapped to a wooden cross and set adrift in the ocean. This death is just the beginning, and Robicheaux – aided, inevitably, by the elemental force that is Cletus Purcel – struggles to find the killer as the manner of the subsequent deaths exceeds abbatoir levels of brutality. There is no shortage of suspects. A driven movie director deeply in hock to criminal backers, a preening and narcissistic former mercenary, a religious crazy man on the run from Death Row – you pays your money and you takes your choice. We even have the return of the bizarre and deranged contract killer known as Smiley – surely one of the most sinister and damaged killers in all crime fiction. Smiley is described as looking like a shapeless white caterpillar. Horrifically abused as a child, he is happiest when buying ice-creams for children – or killing bad people with Dranol or incinerating them with a flame thrower. Even Robicheaux’s new police partner, the fragrantly named Bailey Ribbons is not beyond suspicion.

ith writing that is as potent and smoulderingly memorable as Burke’s, the plot is almost irrelevant, but in between heartbreakingly beautiful descriptions of the dawn rising over Bayou Teche, visceral anger at the damage the oil industry has done to a once-idyllic coast, and jaw-dropping portraits of evil men, Robicheaux patiently and doggedly pursues the killer, and we have a blinding finale which takes The Bobbsey Twins back to their intensely terrified – and terrifying – encounters in the jungles of Indo China.

ith writing that is as potent and smoulderingly memorable as Burke’s, the plot is almost irrelevant, but in between heartbreakingly beautiful descriptions of the dawn rising over Bayou Teche, visceral anger at the damage the oil industry has done to a once-idyllic coast, and jaw-dropping portraits of evil men, Robicheaux patiently and doggedly pursues the killer, and we have a blinding finale which takes The Bobbsey Twins back to their intensely terrified – and terrifying – encounters in the jungles of Indo China.

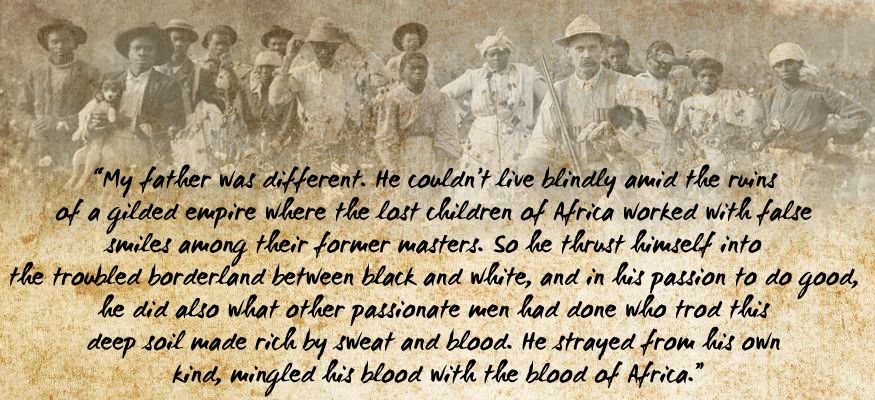

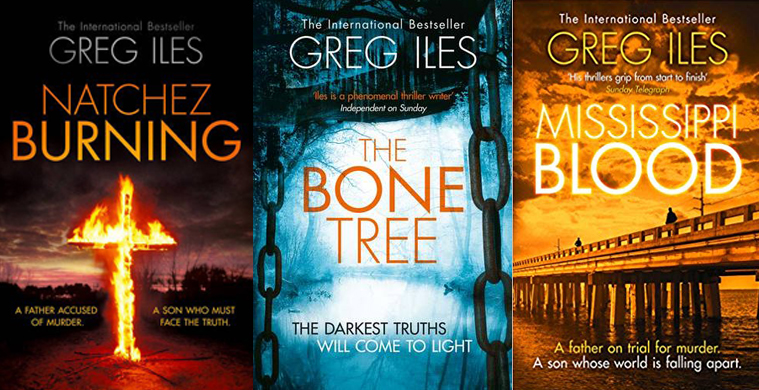

Greg Iles was born in Stuttgart where his father ran the US Embassy medical clinic. When the family returned to the States they settled in Natchez, Mississippi. While studying at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Iles stayed in a cottage where Caroline ‘Callie’ Barr Clark once lived. Callie was William Faulkner’s ‘Mammy Callie’ and different versions of her appear in several of Faulkner’s books. Iles began writing novels in 1993, with a historical saga about the enigmatic Nazi Rudolf Hess, and has written many stand-alone thrillers, but it is his epic trilogy of novels set in Natchez which, in my view, set him apart from anyone else who has ever written in the Southern Noir genre.

Greg Iles was born in Stuttgart where his father ran the US Embassy medical clinic. When the family returned to the States they settled in Natchez, Mississippi. While studying at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Iles stayed in a cottage where Caroline ‘Callie’ Barr Clark once lived. Callie was William Faulkner’s ‘Mammy Callie’ and different versions of her appear in several of Faulkner’s books. Iles began writing novels in 1993, with a historical saga about the enigmatic Nazi Rudolf Hess, and has written many stand-alone thrillers, but it is his epic trilogy of novels set in Natchez which, in my view, set him apart from anyone else who has ever written in the Southern Noir genre.

enn Cage, though, has made his own money. He is a hugely successful author, long-time DA for the County and now, after a bitter political struggle, The Mayor of Natchez. He has made many enemies in his rise to fame, not the least of which are the corrupt Sheriff Byrd and the deeply ambitious and oleaginous public prosecutor Shadrach Johnson. Cage is not without his own ghosts, however, and he is haunted by the death of his wife Sarah, crippled and then tortured by cancer. He has, however, established an unofficial second marriage with the campaigning journalist, Caitlin Masters.

enn Cage, though, has made his own money. He is a hugely successful author, long-time DA for the County and now, after a bitter political struggle, The Mayor of Natchez. He has made many enemies in his rise to fame, not the least of which are the corrupt Sheriff Byrd and the deeply ambitious and oleaginous public prosecutor Shadrach Johnson. Cage is not without his own ghosts, however, and he is haunted by the death of his wife Sarah, crippled and then tortured by cancer. He has, however, established an unofficial second marriage with the campaigning journalist, Caitlin Masters.

o why are the books so good? Penn Cage is a brilliant central character and, of course, he is politically, morally and socially ‘a good man’. His personal tragedies evoke sympathy, but also provide impetus for the things he says and does. Some might criticise the lack of nuance in the novels; there is no moral ambiguity – characters are either venomous white racists or altruistic liberals. Maybe the real South isn’t that simple; perhaps there are white communities who are blameless and tolerant and shrink in revulsion from dark deeds committed by fearsome ex-military psychopaths who seek to restore a natural order that died a century earlier.

o why are the books so good? Penn Cage is a brilliant central character and, of course, he is politically, morally and socially ‘a good man’. His personal tragedies evoke sympathy, but also provide impetus for the things he says and does. Some might criticise the lack of nuance in the novels; there is no moral ambiguity – characters are either venomous white racists or altruistic liberals. Maybe the real South isn’t that simple; perhaps there are white communities who are blameless and tolerant and shrink in revulsion from dark deeds committed by fearsome ex-military psychopaths who seek to restore a natural order that died a century earlier.

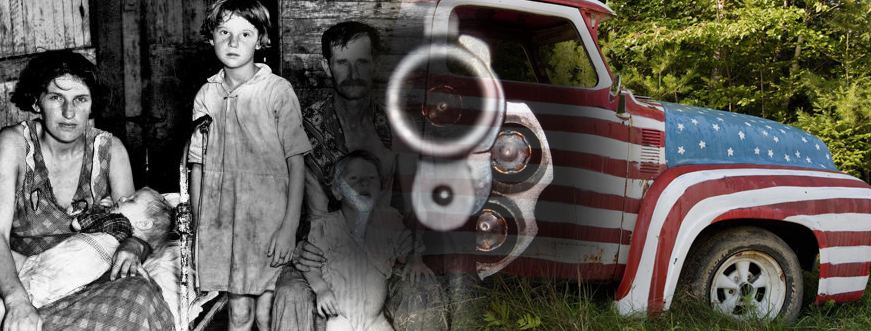

eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or

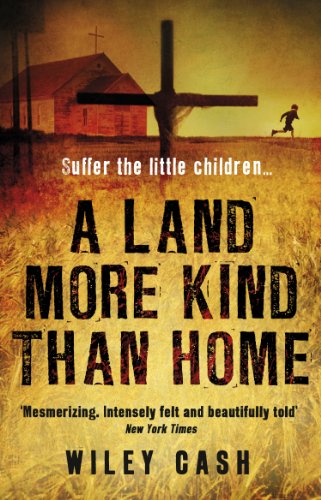

eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or  thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant

thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant  Her best known novel,

Her best known novel,

There have been many commentators, critics and writers who have explored the US North-South divide in more depth and with greater erudition than I am able to bring to the table, but I only seek to share personal experience and views. One of my sons lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is a very modern city. In the 20th century it was a bustling hive of the cotton milling industry, but as the century wore on it declined in importance. Its revival is due to the fact that at some point in the last thirty years, someone realised that the rents were cheap, transport was good, and that it would be a great place to become a regional centre of the banking and finance industry. Now, the skyscrapers twinkle at night with their implicit message that money is good and life is easy.

There have been many commentators, critics and writers who have explored the US North-South divide in more depth and with greater erudition than I am able to bring to the table, but I only seek to share personal experience and views. One of my sons lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is a very modern city. In the 20th century it was a bustling hive of the cotton milling industry, but as the century wore on it declined in importance. Its revival is due to the fact that at some point in the last thirty years, someone realised that the rents were cheap, transport was good, and that it would be a great place to become a regional centre of the banking and finance industry. Now, the skyscrapers twinkle at night with their implicit message that money is good and life is easy. rive out of Charlotte a few miles and you can visit beautifully preserved plantation houses. Some have the imposing classical facades of Gone With The Wind fame, but others, while substantial and sturdy, are more modest. What they have in common today is that your tour guide will, most likely, be an earnest and eloquent young post-grad woman who will be dismissive about the white folk who lived in the big house, but will have much to say the black folk who suffered under the tyranny of the master and mistress.

rive out of Charlotte a few miles and you can visit beautifully preserved plantation houses. Some have the imposing classical facades of Gone With The Wind fame, but others, while substantial and sturdy, are more modest. What they have in common today is that your tour guide will, most likely, be an earnest and eloquent young post-grad woman who will be dismissive about the white folk who lived in the big house, but will have much to say the black folk who suffered under the tyranny of the master and mistress.

By contrast, a day’s drive south will find you in Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston is energetically preserved in architectural aspic, and if you are seeking people to share penance with you for the misdeeds of the Confederate States, you may struggle. In contrast to the spacious and well-funded Levine Museum in Charlotte, one of Charleston’s big draws is The Confederate Museum. Housed in an elevated brick copy of a Greek temple, it is administered by the Charleston Chapter of The United Daughters of The Confederacy. Pay your entrance fee and you will shuffle past a series of displays that would be the despair of any thoroughly modern museum curator. You definitely mustn’t touch anything, there are no flashing lights, dioramas, or interactive immersions into The Slave Experience. What you do have is a fascinating and random collection of documents, uniforms, weapons and portraits of extravagantly moustached soldiers, all proudly wearing the grey or butternut of the Confederate armies. The ladies who take your dollars for admission all look as if they have just returned from taking tea with Robert E Lee and his family.

By contrast, a day’s drive south will find you in Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston is energetically preserved in architectural aspic, and if you are seeking people to share penance with you for the misdeeds of the Confederate States, you may struggle. In contrast to the spacious and well-funded Levine Museum in Charlotte, one of Charleston’s big draws is The Confederate Museum. Housed in an elevated brick copy of a Greek temple, it is administered by the Charleston Chapter of The United Daughters of The Confederacy. Pay your entrance fee and you will shuffle past a series of displays that would be the despair of any thoroughly modern museum curator. You definitely mustn’t touch anything, there are no flashing lights, dioramas, or interactive immersions into The Slave Experience. What you do have is a fascinating and random collection of documents, uniforms, weapons and portraits of extravagantly moustached soldiers, all proudly wearing the grey or butternut of the Confederate armies. The ladies who take your dollars for admission all look as if they have just returned from taking tea with Robert E Lee and his family. Six hundred words in and what, I can hear you say, has this to do with crime fiction? In part two, I will look at crime writing – in particular the work of James Lee Burke and Greg Iles (but with many other references) – and how it deals with the very real and present physical, political and social peculiarities of the South. A memorable quote to round off this introduction is taken from William Faulkner’s Intruders In The Dust (1948). He refers to what became known as The High Point of The Confederacy – that moment on the third and fateful day of the Battle of Gettysburg, when Lee had victory within his grasp.

Six hundred words in and what, I can hear you say, has this to do with crime fiction? In part two, I will look at crime writing – in particular the work of James Lee Burke and Greg Iles (but with many other references) – and how it deals with the very real and present physical, political and social peculiarities of the South. A memorable quote to round off this introduction is taken from William Faulkner’s Intruders In The Dust (1948). He refers to what became known as The High Point of The Confederacy – that moment on the third and fateful day of the Battle of Gettysburg, when Lee had victory within his grasp.