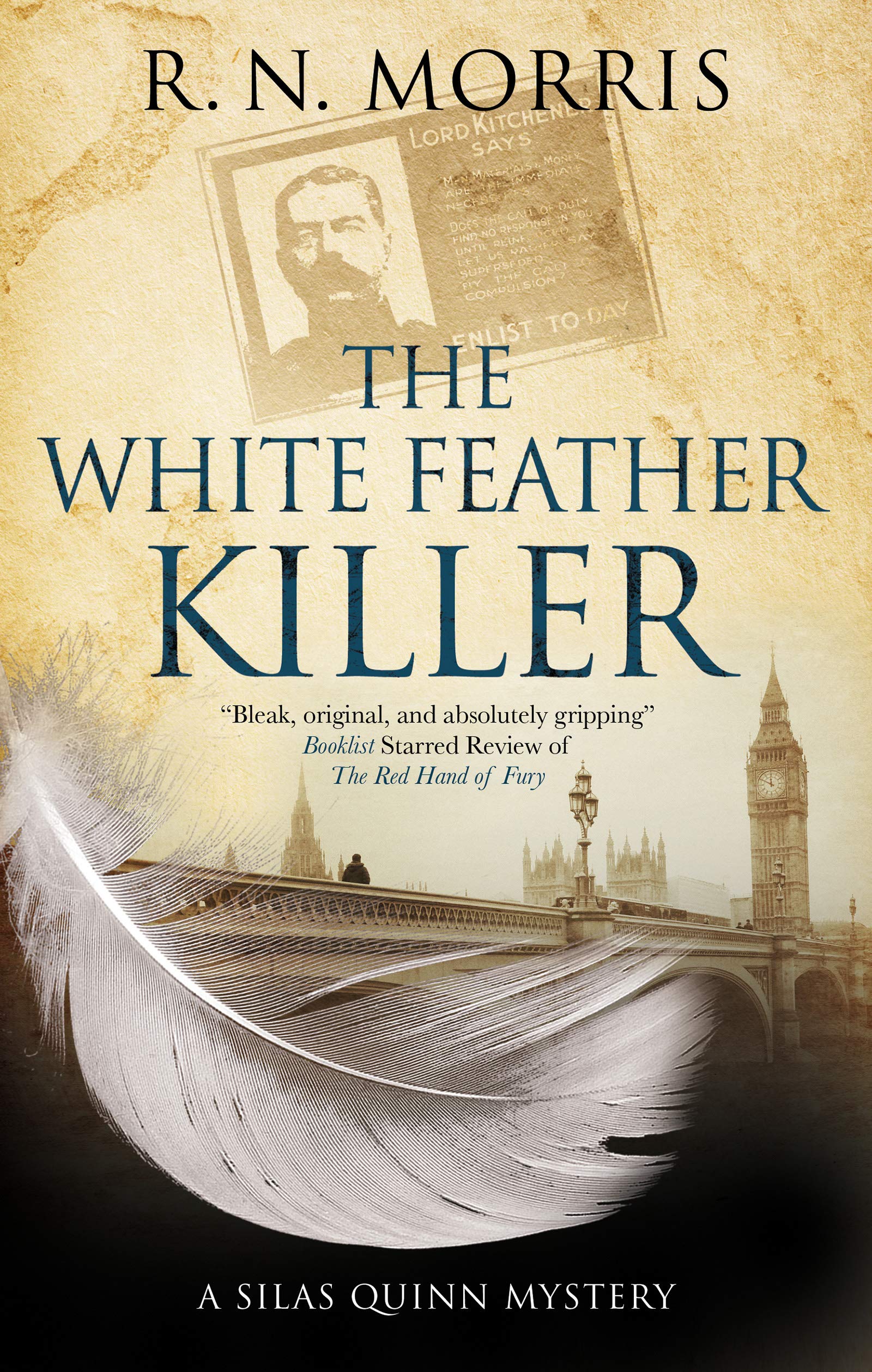

I do love the mysterious world of Detective Inspector Silas Quinn, RN Morris’s rather distinctive London copper from the 1900s. For reviews of earlier novels Summon Up The Blood, The White Feather Killer and The Music Box Enigma click the links. I say “earlier”, but it’s not that simple, as the Silas Quinn books are being reissued by a new publisher, having coming out a few years ago, but since the events they describe are all from a very narrow time frame, the actual chronology doesn’t matter too much.

Quinn and his sergeants – Inchball and Macadam – are The Special Crimes Department of the Metropolitan Police. This department has a passing resemblance to Christopher Fowler’s Peculiar Crimes Unit (Rest In Peace) insofar as the unit has been constructed around the unique talents of its lead investigator. Like Arthur Bryant, Silas Quinn has strange gifts, and is just as likely to exasperate his superior officers as win their praise, but he is a bloody good copper.

Quinn and his sergeants – Inchball and Macadam – are The Special Crimes Department of the Metropolitan Police. This department has a passing resemblance to Christopher Fowler’s Peculiar Crimes Unit (Rest In Peace) insofar as the unit has been constructed around the unique talents of its lead investigator. Like Arthur Bryant, Silas Quinn has strange gifts, and is just as likely to exasperate his superior officers as win their praise, but he is a bloody good copper.

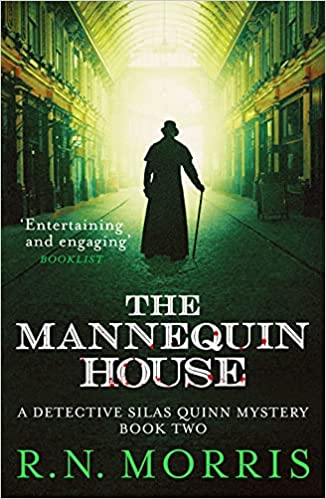

It is March 1914, and most of the citizens of London go about their bustling business oblivious to the gathering storm which would break over their heads in just a few months. Blackley’s Emporium is one of the most successful department stores in the city. You can buy anything and everything that is made, mined or grown on God’s earth, and you may even be greeted by the beaming proprietor himself as you walk through the doors. You can even – should you be minded to take a break from spending money – visit the in-house menagerie which is full of weird and exotic creatures.

One of Benjamin Blackley’s most profitable departments is his haute couture fashion house, where (plus ça change) slender young women wearing must-have gowns and fripperies parade in front of not-so-slender older women. Blackley ‘keeps’ – and I use the word advisedly – his slips of things in a suburban house, presided over by a formidable matron. When the most beautiful of these mannequins – Amélie – doesn’t turn up for work, and her room is found locked from the inside, the police are called. Two things happen when the door is eventually opened. First, an enraged Macaque monkey runs screaming from the room and, second, Amélie has a very good excuse for missing work, as she is dead on her bed, strangled with a silk scarf.The subsequent post-mortem examination reveals that the girl may have been raped, and also that she has maintained her desirability as a fashion model by disastrous self-abuse of her body.

Morris takes the classic ‘locked room’ trope and has his wicked way with it. There is some knockabout comedy in this book, particularly with Quinn’s wildly contrasting underlings Inchball and Macadam, but there is a vein of darker material running through the narrative. Quinn may be a clever copper, but he is also psychologically damaged from a traumatic childhood. The uneasy personal dynamics between fellow lodgers at the house where Quinn sleeps are a signal that the detective is not at ease with other people. It has to be said, that later (already available) Silas Quinn novels shine a revealing light on this situation. There is great fun to be had within the pages of The Mannequin House, but we are never far away from the evil that men (and women) do, and you must be prepared for a rather shocking and violent end to the story.

As ever, Roger Morris gives us a delicious mystery, a totally authentic background and an absorbing book into which we can escape for a few precious hours. The Mannequin House was first published in 2013, but this new paperback edition from Canelo is out now.

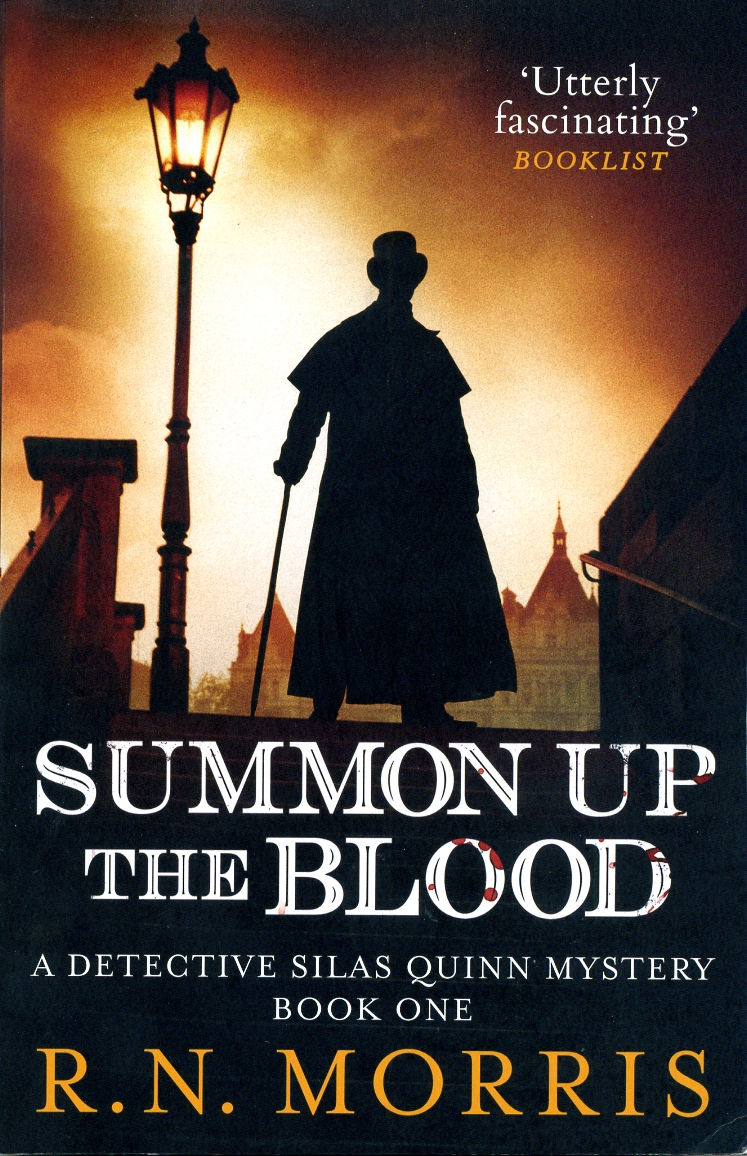

When a rent boy is found dead, his throat cut from ear to ear, there is initially little interest by the police, as the lad is just assumed to have paid the price for being in a risky line of business, but when the post mortem reveals that he has had every drop of blood drained from his body, Quinn is summoned and told to investigate. After a droll episode where Quinn decides to pose as a man smitten by “the love that dare not speak its name”, and blunders around in a dodgy bookshop, but he does find out that the dead youngster was called Jimmy, and had links to a ‘gentleman’s club’ where he would find men appreciative of his talents.

When a rent boy is found dead, his throat cut from ear to ear, there is initially little interest by the police, as the lad is just assumed to have paid the price for being in a risky line of business, but when the post mortem reveals that he has had every drop of blood drained from his body, Quinn is summoned and told to investigate. After a droll episode where Quinn decides to pose as a man smitten by “the love that dare not speak its name”, and blunders around in a dodgy bookshop, but he does find out that the dead youngster was called Jimmy, and had links to a ‘gentleman’s club’ where he would find men appreciative of his talents.

Thankfully, Morris makes no attempt to get in the politics of homosexuality and the law: his characters simply inhabit the world in which he puts them, and their thoughts, words and deeds resonate authentically. In 1914, remember, the trial of Oscar Wilde and the Cleveland Street Scandal were still part of folk memory. It’s an astonishing thought that had Morris been writing about similar murders, fifty years later in 1964, virtually nothing would have changed – think of the scandals involving such ‘big names’ as Tom Driberg, Robert Boothby and Ronnie Kray, and how their lives have been written up by such novelists as Jake Arnott, John Lawton and James Barlow.

Thankfully, Morris makes no attempt to get in the politics of homosexuality and the law: his characters simply inhabit the world in which he puts them, and their thoughts, words and deeds resonate authentically. In 1914, remember, the trial of Oscar Wilde and the Cleveland Street Scandal were still part of folk memory. It’s an astonishing thought that had Morris been writing about similar murders, fifty years later in 1964, virtually nothing would have changed – think of the scandals involving such ‘big names’ as Tom Driberg, Robert Boothby and Ronnie Kray, and how their lives have been written up by such novelists as Jake Arnott, John Lawton and James Barlow.

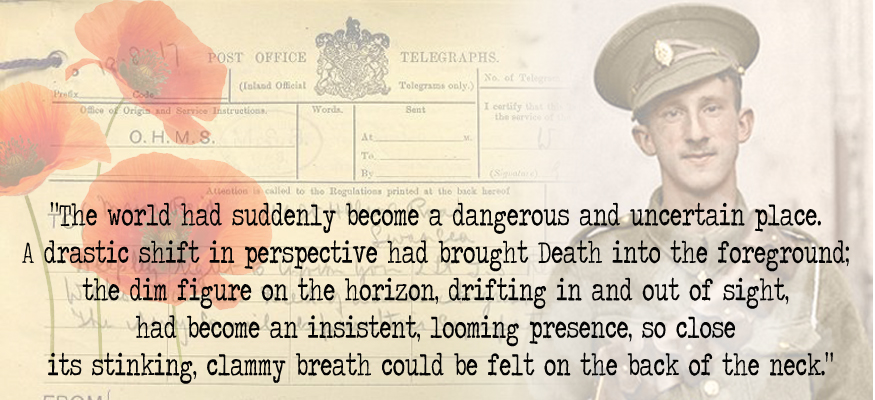

I’m a great fan of historical crime fiction, particularly if it is set in the 19th or 20th centuries, but I will be the first to admit that most such novels tend not to veer towards what I call The Dark Side. Perhaps it’s the necessary wealth of period detail which gets in the way, and while some writers revel in the more lurid aspects of poverty, punishment and general mortality, the genre is usually a long way from noir. That’s absolutely fine. Many noir enthusiasts (noiristes, perhaps?) avoid historical crime in the same way that lovers of a good period yarn aren’t drawn to existential world of shadows cast by flickering neon signs on wet pavements. The latest novel from RN Morris, The White Feather Killer is an exception to my sweeping generalisation, as it is as uncomfortable and haunting a tale as I have read for some time.

I’m a great fan of historical crime fiction, particularly if it is set in the 19th or 20th centuries, but I will be the first to admit that most such novels tend not to veer towards what I call The Dark Side. Perhaps it’s the necessary wealth of period detail which gets in the way, and while some writers revel in the more lurid aspects of poverty, punishment and general mortality, the genre is usually a long way from noir. That’s absolutely fine. Many noir enthusiasts (noiristes, perhaps?) avoid historical crime in the same way that lovers of a good period yarn aren’t drawn to existential world of shadows cast by flickering neon signs on wet pavements. The latest novel from RN Morris, The White Feather Killer is an exception to my sweeping generalisation, as it is as uncomfortable and haunting a tale as I have read for some time. orris takes his time before giving us a dead body, but his drama has some intriguing characters. We met Felix Simpkins, such a mother’s boy that, were he to be realised on the screen, we would have to resurrect Anthony Perkins for the job. His mother is not embalmed in the apple cellar, but an embittered and waspish German widow, a failed concert pianist, a failed wife, and a failed pretty much everything else except in the dubious skill of humiliating her hapless son. Central to the grim narrative is the Cardew family. Baptist Pastor Clement Cardew is the head of the family; his wife Esme knows her place, but his twin children Adam and Eve have a pivotal role in what unfolds. The trope of the hypocritical and venal clergyman is well-worn but still powerful; when we realise the depth of Cardew’s descent into darkness, it is truly chilling.

orris takes his time before giving us a dead body, but his drama has some intriguing characters. We met Felix Simpkins, such a mother’s boy that, were he to be realised on the screen, we would have to resurrect Anthony Perkins for the job. His mother is not embalmed in the apple cellar, but an embittered and waspish German widow, a failed concert pianist, a failed wife, and a failed pretty much everything else except in the dubious skill of humiliating her hapless son. Central to the grim narrative is the Cardew family. Baptist Pastor Clement Cardew is the head of the family; his wife Esme knows her place, but his twin children Adam and Eve have a pivotal role in what unfolds. The trope of the hypocritical and venal clergyman is well-worn but still powerful; when we realise the depth of Cardew’s descent into darkness, it is truly chilling. Historical novels come and go, and all too many are over-reliant on competent research and authentic period detail, but Morris (right) plays his ace with his brilliant and evocative use of language. Here, Quinn watches, bemused, as a company of army cyclists spin past him:

Historical novels come and go, and all too many are over-reliant on competent research and authentic period detail, but Morris (right) plays his ace with his brilliant and evocative use of language. Here, Quinn watches, bemused, as a company of army cyclists spin past him: uinn has to pursue his enquiries in one of the quieter London suburbs, and makes this wry observation of the world of Mr Pooter – quaintly comic, but about to be shattered by events:

uinn has to pursue his enquiries in one of the quieter London suburbs, and makes this wry observation of the world of Mr Pooter – quaintly comic, but about to be shattered by events: