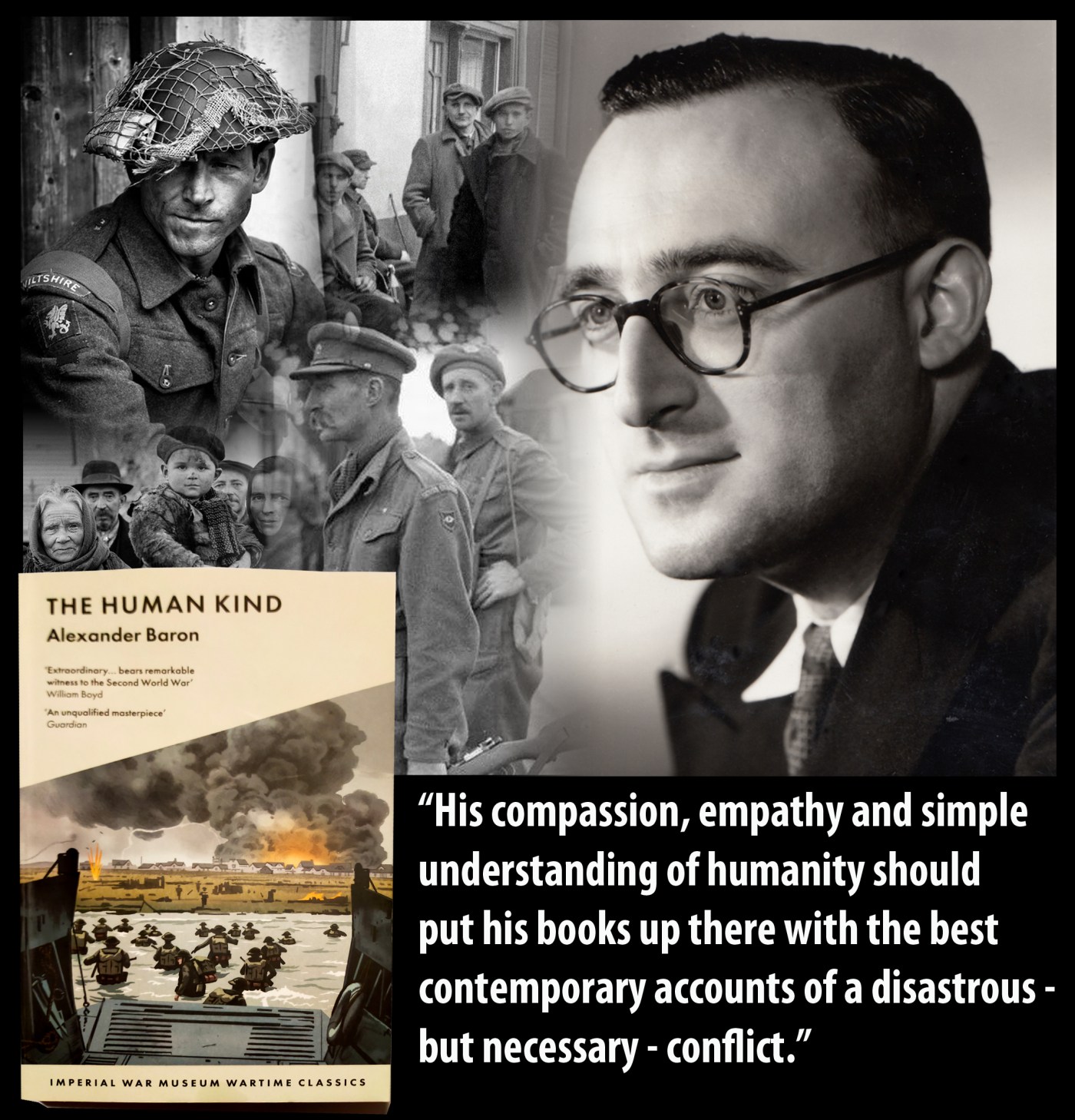

This is the third novel in Alexander Baron’s WW2 trilogy, and it is rather different to the previous books, although there are obvious links. From The City, From The Plough tells the story of a group of soldiers preparing for, and then taking part in, the invasion of Normandy in 1944, while in There’s No Home the focus is on just a few weeks where an army company takes up residence in the Sicilian town of Catania in 1943. The titles are hyperlinked to my reviews of the novels.

The Human Kind is a sequence of short stories or vignettes, presented as being mainly autobiographical, and they reflect a wide variety of incidents and experiences involving men at arms. I use that phrase intentionally. I an surely not the first person to compare Baron’s trilogy with Evelyn Waugh’s magisterial Sword of Honour trilogy, which comprised Men at Arms, Officers and Gentlemen and Unconditional Surrender. There are stark differences, obviously, in that Waugh’s novels saw soldiering through the eyes of middle class officers. The central character, Guy Crouchback, is from a minor-aristocratic Roman Catholic family, while Baron was a Jewish man from London’s East End. What connects the two trilogies, however, is keen social observation, repeated ironies of circumstance and – most importantly – the fact that for many men the war and military life became central to their very being, despite the obvious hazards and unpleasantness. Baron – a communist in his youth – himself probably despised Waugh’s upper-middle-class reactionary views but he admired his writing, saying it was, “a magnificent illumination of a whole complex of human problems.”

Each of the stories except one, which I will return to, references the military campaigns – Italy, Normandy and Belgium – described in the earlier books. The one that affected me most was Mrs Grocott’s Boy. Raymond Grocott comes from The Potteries, where he lives with his widowed mother. He is, to use an old word, gormless. Nowadays, I suppose, he would have been long since diagnosed with ‘special needs’, and he has failed the basic intelligence test required to be admitted to the army. Having persuaded those in authority to let him join, he takes part in the invasion of Sicily. Contracting malaria, he is invalided out, but is desperate to rejoin his unit which, with some degree of innate cunning, he does. In a stroke of irony that Thomas Hardy would have loved, his company is selected to be shipped home to prepare for the Normandy landings. Out of a misplaced sense of kindness, Raymond’s fellow soldiers cover for him and try to keep him on the straight and narrow paths but, as the landing craft approaches the French beach it finally dawns on him that he could be killed, and he pleads to be sent to the rear for medical attention. It is too late. Somehow, he survives, having been driven on by an NCO. But when what remains of the platoon finally bivouacs in a relatively safe place, he is handed a written order transferring him away from danger and into the care of the medics. As he trudges away, he has a solitary flash of self awareness and he curses the well-meaning men who have delivered him to a place of shame. His parting words to his colleagues are, “I hope you die. I hope you all die.”

There is black humour in some of the stories, as well as a dark awareness of sexuality. In Chicolino, the soldiers in Baron’s platoon ‘adopt’ a homeless Sicilian boy, just into his teens. They share rations with him and treat him kindly, but are shocked to the core when he assumes that they will want to have sex with him in return for their kindness. He would have been quite happy to oblige, and is hurt and humiliated by their rejection. In The Indian, Baron retells the story from There’s No Home of how Sergeant Craddock comes to sleep with the beautiful Graziela. It is the appearance of a drunk but harmless Indian soldier that brings them into each other’s arms. Readers who, like me, are long in the tooth, will remember watching a 1963 movie called The Victors, directed by Carl Foreman. Alexander Baron was the screenwriter, and the story Everybody Loves a Dog, which relates the unfortunate consequences of a friendless and inarticulate Yorkshire soldier befriending a stray dog, was one of many memorable scenes in the film.

There is black humour in some of the stories, as well as a dark awareness of sexuality. In Chicolino, the soldiers in Baron’s platoon ‘adopt’ a homeless Sicilian boy, just into his teens. They share rations with him and treat him kindly, but are shocked to the core when he assumes that they will want to have sex with him in return for their kindness. He would have been quite happy to oblige, and is hurt and humiliated by their rejection. In The Indian, Baron retells the story from There’s No Home of how Sergeant Craddock comes to sleep with the beautiful Graziela. It is the appearance of a drunk but harmless Indian soldier that brings them into each other’s arms. Readers who, like me, are long in the tooth, will remember watching a 1963 movie called The Victors, directed by Carl Foreman. Alexander Baron was the screenwriter, and the story Everybody Loves a Dog, which relates the unfortunate consequences of a friendless and inarticulate Yorkshire soldier befriending a stray dog, was one of many memorable scenes in the film.

One of Baron’s colleagues is an intelligent and educated man called Frank Chase. In The Venus Bar, we read of his liaison with a beautiful but ruthless Ostend brothel owner. but in Victory Night, the war has taken its toll and Chase is shipped home, psychologically broken. He is hospitalised, but can make no sense of his situation.

“He was too bewildered to fight against his loneliness. He did not visit London. It was only to the immediate past, to us, that his memory was able to reach. Peace time had passed out of his life. He was afraid to go to London in search of the ends of long-broken threads. He wondered about in a days, hardly aware of anything that happened except the arrival of letters from his old comrades. He hugged these to him, for they were the raw material of dreams, daydreams that burst inside him like magnesium flares, illuminating with brief, ghostly intensity the supreme experiences he had to live through.”

When victory in Europe is finally declared, Chase is horrified by the drunken celebrations in an English village.

“The faces streamed past him, faces for a Bruegel, red and ugly with drink, the fat faces of alewives glistening with the distant firelight, the suet- lump faces of men who had not been judged young or intelligent enough to die, the vacuous whore-faces, pathetically greedy for pleasure, of little village girls. They squealed and shrieked, filled the night with graceless laughter, bawled idiot songs, coughed, screamed, yelled and belched.”

There are twenty five stories in all in The Human Kind, and all but two are reflections on Baron’s war service. The last one, An Epilogue, is a brief story of something that happened in the Korean War, by which time Baron had been in ‘civvy street’ for some time, but Strangers To Death, the first tale in the book, recounts an incident from Baron’s childhood. He says he was sixteen at the time, so this would place the events in the summer of 1933. He is the proud owner of a new sports bicycle, and he joins a group of local youngsters who cycle out from their East End homes to nearby countryside to camp on the banks of the River Lea. Here, they swim, smoke, cook meals and relish the fresh air, but when one of their number is trapped in the silk-weed growing from the river bed, and drowns, the atmosphere becomes sombre. It was probably Baron’s first intimate encounter with death, but with the insouciance of youth, he and his mates are soon back in the river, daring each other to play tug-of-war with the silk-weed and trying to get as close to the treacherous currents of a weir as they dare. On the way home, Baron comes even closer to death when, his spectacles blurred by rain, he collides with a tram. Miraculously, he is thrown clear, unharmed apart from a graze, and even his precious ‘Silver Wing’ bicycle is undamaged. He would of course, come to stare death in the face all too frequently just ten years later.

It would be inaccurate to say that Baron is a ‘forgotten’ writer, but his name would not be included in most people’s list of great English writers of the final decades of the twentieth century. Many of his other novels, often set in the Jewish London of his youth, are still in print, but his take on what war does to men, women and children is astonishing. His compassion, empathy and simple understanding of humanity should put his books up there with the best contemporary accounts of a disastrous – but necessary – conflict. The Human Kind is republished by The Imperial War Museums,and is available now.

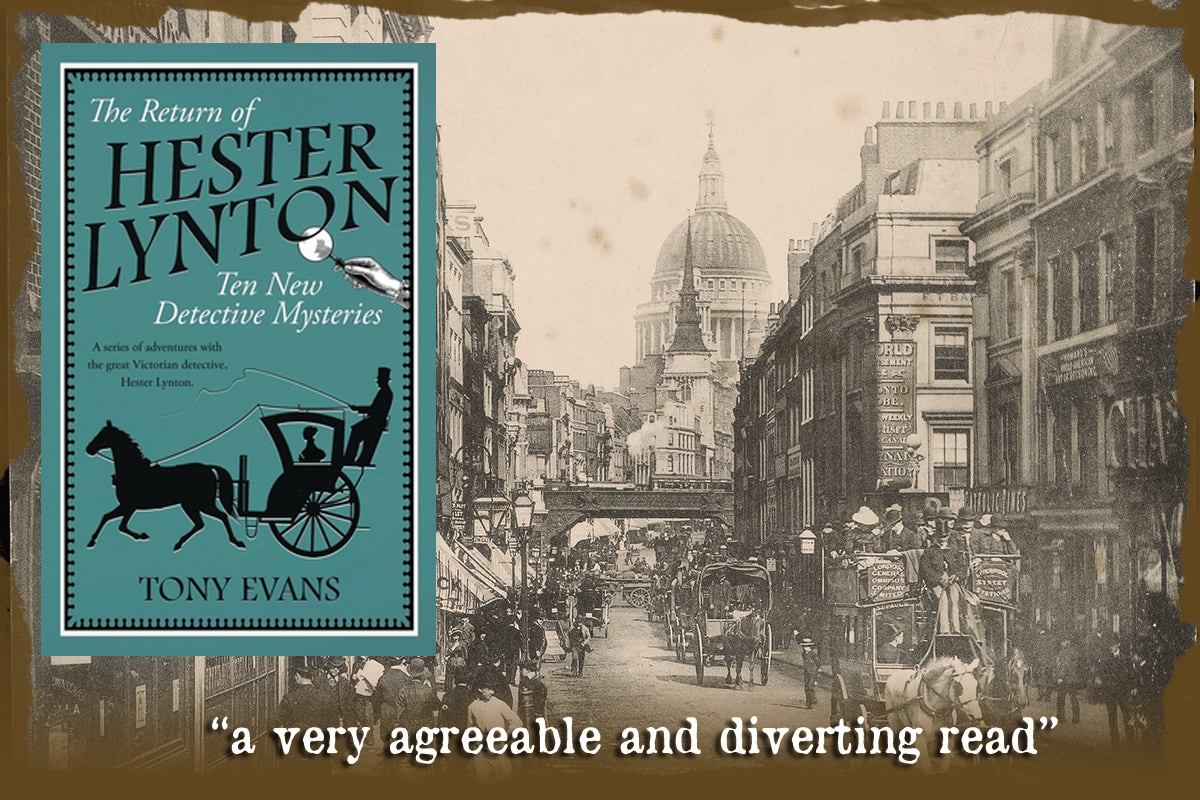

A rich widower, a self made industrialist, dies and leaves his fortune to be divided between his two nephews. One is a down-at-heel schoolmaster, the other a disreputable roué. The lucky man has to solve a cypher set by their late uncle. The good guy brings the cypher to Hester and Ivy. They solve the conundrum with by way of a knowledge of 18th century first editions, a journey to explore an ancient English church, and by breaking in to a family mausoleum.

A rich widower, a self made industrialist, dies and leaves his fortune to be divided between his two nephews. One is a down-at-heel schoolmaster, the other a disreputable roué. The lucky man has to solve a cypher set by their late uncle. The good guy brings the cypher to Hester and Ivy. They solve the conundrum with by way of a knowledge of 18th century first editions, a journey to explore an ancient English church, and by breaking in to a family mausoleum. Here, Tony Evans (right) indulges in the first of two shameless – but entertaining – instances of name-dropping. Our two sleuths, weary after a succession of difficult investigations, are enjoying some well-earned R & R in the resort of Whitby. So who do they meet? Think Irish writer and man of the theatre, blood, fangs …..? Gotcha! They are engaged by a fellow holidaymaker, a certain Mr B. Stoker to investigate the disappearance of a housemaid. She has been induced to leave her present employment to go and work for a rather dodgy doctor. Much skullduggery ensues, the housemaid is saved, and Mr Stoker says, “Hmm – this gives me an idea for a story.”

Here, Tony Evans (right) indulges in the first of two shameless – but entertaining – instances of name-dropping. Our two sleuths, weary after a succession of difficult investigations, are enjoying some well-earned R & R in the resort of Whitby. So who do they meet? Think Irish writer and man of the theatre, blood, fangs …..? Gotcha! They are engaged by a fellow holidaymaker, a certain Mr B. Stoker to investigate the disappearance of a housemaid. She has been induced to leave her present employment to go and work for a rather dodgy doctor. Much skullduggery ensues, the housemaid is saved, and Mr Stoker says, “Hmm – this gives me an idea for a story.”