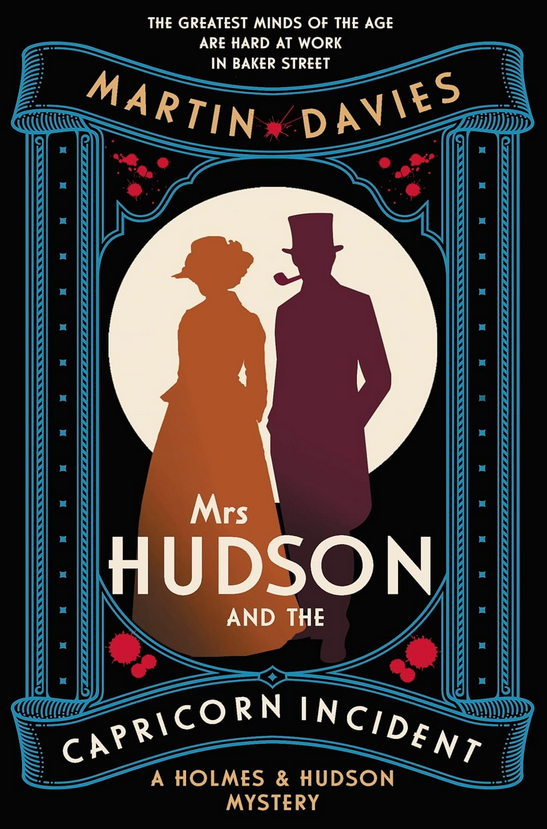

The canonical 56 short stories and four novellas featuring Sherlock Holmes have left so-called ‘continuation’ authors with plenty of subordinate characters to draw on. Dr Watson, inspector Lestrade, Moriarty and brother Mycroft have each been the central character in novels. I suppose it was only a matter of time before Mrs Hudson took centre stage. Martin Davies took up the challenge in 2002 with Mrs Hudson and the Spirit’s Curse, but here, events are narrated by a girl called Flotsam, who recalls events rather in the way that the good Doctor reminisces about the cases his old friend solved.

Flottie was an orphan girl, saved from a life of degradation by the kindness of Mrs Hudson, but is now a very bright young woman who has seeks education where and whenever she can find it. She is now highly literate and socially adept (but still working downstairs).The story unfolds through her eyes and ears. The substantive plot centres on Rosenau, a tiny Duchy in the Balkans, squeezed between the competing demands of the ailing Ottoman empire, Austria-Hungary and fervent Serbian nationalists. It’s survival depends on an impending marriage between Count Rudolph and Princess Sophie who, hopefully will provide a legitimate heir, ensuring the Duchy’s survival. Rosenau is, of course, fictional, but the Balkan powder keg was, at the turn of the century, frighteningly real. Everything goes awry when, first, the Count goes missing while on a European skiing trip and, second, when the princess is abducted from a London residence.

Reviewers and critics are perfectly entitled to question the validity of the still-vibrant Sherlock Holmes industry. Why, over a century after the last Conan Doyle tale was published, are we still seeing (and here, choose your own description) continuations, homages, pastiches and re-imaginings of crime fiction’s most celebrated character? The answer is simple – because people buy the books or borrow them from the library. Conan Doyle tired of his man, and tried to end it all, in the hope that readers would be drawn towards his other novels, like Micah Clarke or the Brigadier Gerard series. He was forced to relent. As a former prime minister said, “You can’t buck the market.” She was correct, and it must be assumed that two decades after the first novel in the series, people still buy these books and, for publishers, that is it and all about it.

Is this book any good? Yes, of course. Conan Doyle planted a seed which has grown into the mother of all beanstalks, and the Sherlock Holmes phenomenon is as busy as it ever was. Martin Davies reconnects us to a world which is endlessly appealing: chaste bachelors of independent means, a strictly ordered society, a London unsullied by antisemitic mobs, a railway system that ran with clockwork precision, handwritten letters delivered several times daily, a world that challenged the chant of Macbeth’s witches, ‘fair is foul and foul is fair’. This moral ambiguity has no place in the world of Mrs Hudson or Flottie. The tone of the book? Light of heart in some ways, with a certain amount of comedy. Here, a caricature aristocratic old gent opines on marriage:

“Wedding, for goodness sake? Weddings are ten a penny. When I was a lad, a man got married in the morning, introduced his wife to his mistress at lunchtime, and was at the races in the afternoon. And so long as he honored his debts, no one thought the worse of him.”

The humour reminded me very much the very underrated series of Inspector Lestrade novels by MJ Trow. As in those novels. this author provides some good jokes: A famous actress confides in Flottie.

“The important thing is to remember that your skirts are your enemy and speed is your friend. Which is quite the opposite of how we usually think about things, isn’t it?”

She is talking about the new enthusiasm among young women for cycling.

I have made this point before, but it is worth repeating. The canonical Holmes short stories were just that – short. Conan Doyle could take one problem, and allow his man to solve it in just a few pages. Even the four novels were brief. Short stories don’t sell these days and the concept of novels serialised in print and paper magazines is dead and buried, therefore modern Holmes emulators have to spin out the narrative to the regulation 300-400 pages. So, there has to be subplots and other investigations going on, and this almost always means that the narrative tends to drift. So it is here, with the Rosenau crisis sharing the pages with the search for someone called Maltravers, a serial swindler. Martin Davies handles this dilemma as well as anyone else, and presents us with an entertaining tale that is well worth a few hours of anyone’s time. There were occasional longeurs, but the last few pages were rather wonderful. Mrs Hudson and the Capricorn Incident is published by Allison & Busby and is available now.

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

We are in London in the summer of 1879, and young Holmes has yet to meet the man who will write up his greatest cases. Holmes works for a guinea a day, and is striving to build his reputation. Within the first few pages, he has been hired to investigate two cases on behalf of a man who was already a celebrity, and another who would become infamous in his lifetime, but revered and admired after his death. The celebrity is Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, a notorious Lothario whose battleground has been country houses and mansions the length and breadth of the country, the vanquished being a long list of cuckolded husbands. It seems that the heir to the throne has been in the habit of entering his sexual achievements in a diary – a kind of fornicator’s Bradshaw, if you will – but it has gone missing, and Holmes is charged with recovering it.

We are in London in the summer of 1879, and young Holmes has yet to meet the man who will write up his greatest cases. Holmes works for a guinea a day, and is striving to build his reputation. Within the first few pages, he has been hired to investigate two cases on behalf of a man who was already a celebrity, and another who would become infamous in his lifetime, but revered and admired after his death. The celebrity is Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, a notorious Lothario whose battleground has been country houses and mansions the length and breadth of the country, the vanquished being a long list of cuckolded husbands. It seems that the heir to the throne has been in the habit of entering his sexual achievements in a diary – a kind of fornicator’s Bradshaw, if you will – but it has gone missing, and Holmes is charged with recovering it. One hundred pages in, and it is clear that the author is enjoying a glorious exercise in name-dropping. James McNeill Whistler, Lillie Langtry, Francis Knollys, Patsy Cornwallis-West, Frank Miles, Sarah Bernhardt, John Everett Millais and Rosa Corder (right) are just a few of the real life characters who make an appearance, and it is clear that ‘Sherlock Holmes’ moves in very elegant circles.

One hundred pages in, and it is clear that the author is enjoying a glorious exercise in name-dropping. James McNeill Whistler, Lillie Langtry, Francis Knollys, Patsy Cornwallis-West, Frank Miles, Sarah Bernhardt, John Everett Millais and Rosa Corder (right) are just a few of the real life characters who make an appearance, and it is clear that ‘Sherlock Holmes’ moves in very elegant circles.

In a sappingly hot Indian Summer in central London, Dr John Watson is sent – by a relative he hardly remembers – a mysterious tin box which has no key, and no apparent means by which it can be opened. Watson and his companion Sherlock Holmes have become temporarily estranged, not because of any particular antipathy, but more because the investigations which have brought them so memorably together have dwindled to a big fat zero.

In a sappingly hot Indian Summer in central London, Dr John Watson is sent – by a relative he hardly remembers – a mysterious tin box which has no key, and no apparent means by which it can be opened. Watson and his companion Sherlock Holmes have become temporarily estranged, not because of any particular antipathy, but more because the investigations which have brought them so memorably together have dwindled to a big fat zero. But then, in the space of a few hours, Watson shows his mysterious box to his house-mate, and the door of 221B Baker Street opens to admit two very different visitors. One is a young Roman Catholic novice priest from Cambridge who is worried about the disappearance of a young woman he has an interest in, and the second is a voluptuous conjuror’s assistant with a very intriguing tale to tell. The conjuror’s assistant, Madam Ilaria Borelli is married to one stage magician, Dario ‘The Great’ Borelli, but is the former lover of his bitter rival, Santo Colangelo. Are the two showmen trying to kill each other for the love of Ilaria? Have they doctored each other’s stage apparatus to bring about disastrous conclusions to their separate performances?

But then, in the space of a few hours, Watson shows his mysterious box to his house-mate, and the door of 221B Baker Street opens to admit two very different visitors. One is a young Roman Catholic novice priest from Cambridge who is worried about the disappearance of a young woman he has an interest in, and the second is a voluptuous conjuror’s assistant with a very intriguing tale to tell. The conjuror’s assistant, Madam Ilaria Borelli is married to one stage magician, Dario ‘The Great’ Borelli, but is the former lover of his bitter rival, Santo Colangelo. Are the two showmen trying to kill each other for the love of Ilaria? Have they doctored each other’s stage apparatus to bring about disastrous conclusions to their separate performances?