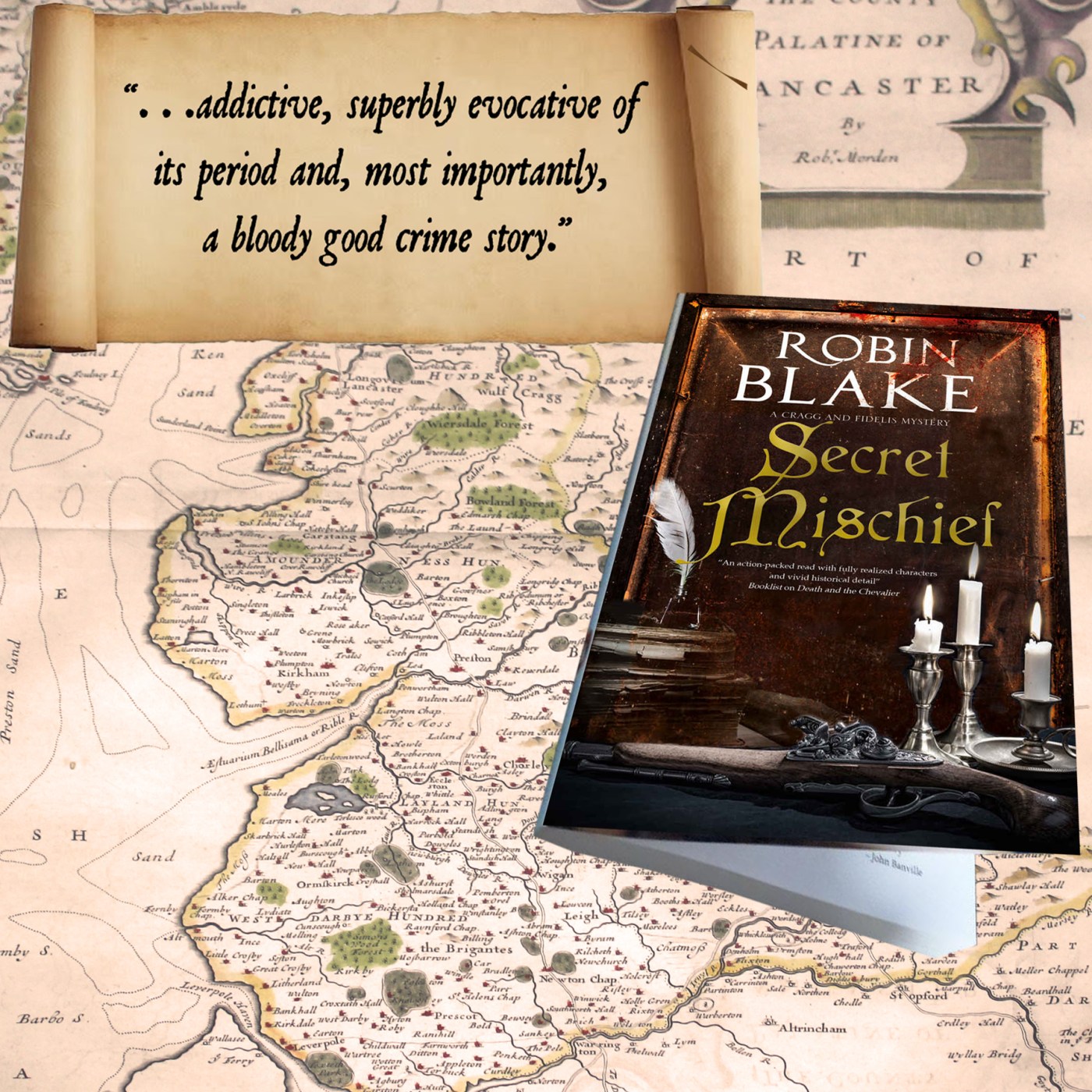

I have become a huge fan of the Cragg and Fidelis books written by Preston-born Robin Blake. They are set in the 1740s in Lancashire, Titus Cragg is the county coroner, and his friend Luke Fidelis is an enterprising and innovative young physician. Hungry Death is the eighth in this excellent series, and to read my reviews of three of the previous books Skin and Bone, Rough Music, and Secret Mischief, click the links.

Cragg is instructed to ride out to a lonely moorland farmhouse, and what he finds surpasses any of the previous horrors his calling requires him to confront. He finds an entire family slaughtered, by whose hand he knows not, unless it was the husband of the house, himself hanging by a strap hooked over a beam. To add even more mystery to the grisly tableau, Cragg learns that the KIdd family were members of a bizarre dissenting cult which encourages its members into acts of brazen sexuality. Then, in a seemingly unconnected incident, the gardener at a nearby mansion, trying to improve the drainage under his hothouse, discovers another body. This corpse may have been in the ground for centuries, as it has been partly preserved by the peat in which it was buried. When Fidelis conducts an autopsy, however, he concludes that the body is that of a young woman, and was probably put in the ground within the last decade or so.

Cragg is instructed to ride out to a lonely moorland farmhouse, and what he finds surpasses any of the previous horrors his calling requires him to confront. He finds an entire family slaughtered, by whose hand he knows not, unless it was the husband of the house, himself hanging by a strap hooked over a beam. To add even more mystery to the grisly tableau, Cragg learns that the KIdd family were members of a bizarre dissenting cult which encourages its members into acts of brazen sexuality. Then, in a seemingly unconnected incident, the gardener at a nearby mansion, trying to improve the drainage under his hothouse, discovers another body. This corpse may have been in the ground for centuries, as it has been partly preserved by the peat in which it was buried. When Fidelis conducts an autopsy, however, he concludes that the body is that of a young woman, and was probably put in the ground within the last decade or so.

Bodies – dead ones – are central to Titus Cragg’s world. A coroner, then and now, must try to be led, hand in hand, by the dead until the circumstances of their demise is revealed. Sometimes, through his investigations and observations, Cragg (helped by the medical eye of Fidelis) can make the dead talk, but the peat-blackened young woman seems to have little to say. Painstaking and shrewd deduction leads Cragg to believe that she was a servant girl once employed at one of the large households in the area. But who? The girls came and went, changed their names through marriage, and the passing years have cast a shroud of fog over the matter.

Regarding the slaughter at the farmhouse, Cragg discovers that the answer lies in the peculiar – and vengeful – nature of the Eatanswillian sect. I believe Robin Blake has used a little historical license here, as the only mention of the word online that I could find is that of the election in the fictional town of Eatanswill (described so satirically in The Pickwick Papers). The resolution of the case hinges on a note pinned to the door of the farmhouse, apparently written in some kind of code. Cragg hopes that deciphering the code will lead him to the perpetrator of the slaughter.

All is resolved, of course, in the final pages, which are framed around the coroner’s inquest into both cases, and Robin Blake gives us a courtroom drama worthy of anything in the distinguished career of Perry Mason or, more recently Micky Haller. This is a cracking piece of historical crime fiction from the first word to the last, but I have to say the opening chapter was one of the most horrific passages I have read for a long time. Hungry Death is published by Severn House and is available now.

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot.

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot. One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

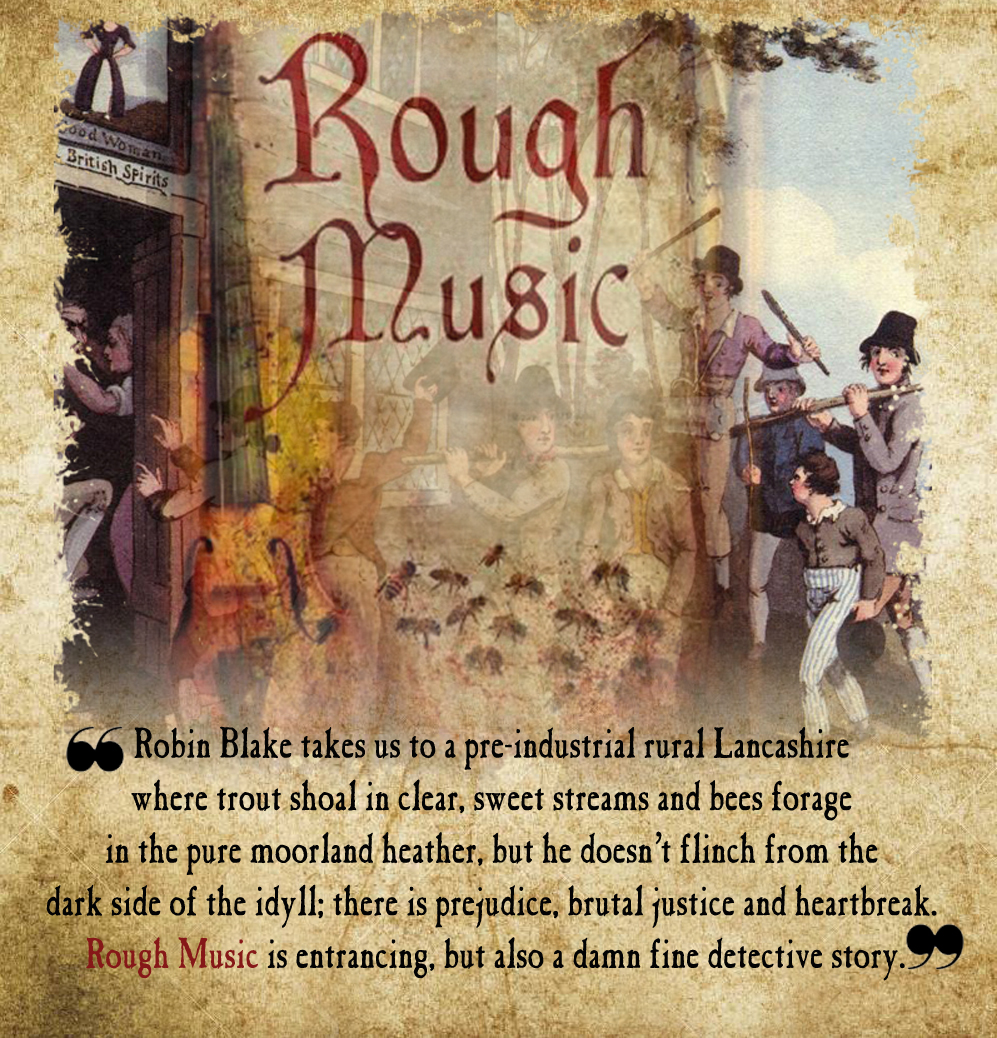

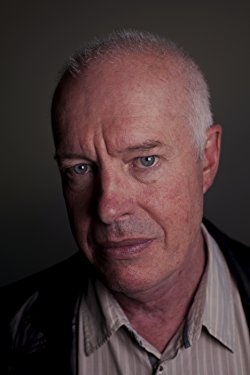

Robin Blake (left) introduced us to Preston coroner Titus Cragg and his physician friend Luke Fidelis in A Dark Anatomy back in 2015, and the pair of eighteenth century sleuths are back again with their fifth case, Rough Music.

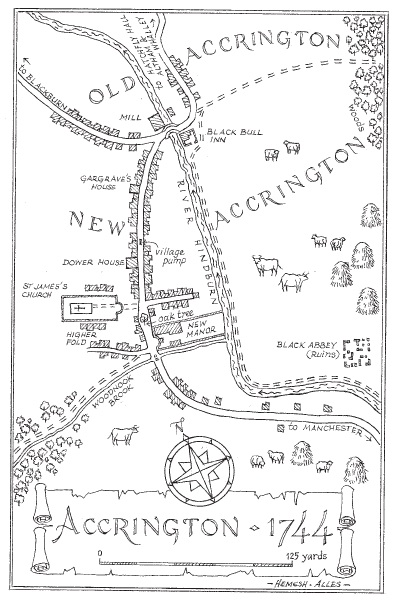

Robin Blake (left) introduced us to Preston coroner Titus Cragg and his physician friend Luke Fidelis in A Dark Anatomy back in 2015, and the pair of eighteenth century sleuths are back again with their fifth case, Rough Music. Titus Cragg with his wife and child have retreated from Preston to escape the ravages of a viral illness which has claimed the lives of many infants. They have fetched up in a rented house in Accrington, then little more than a scattering of houses beside a stream. Cragg is drawn into the investigation of how it was that Anne Gargrave died at the hands of her fellow villagers, but his work is complicated by a feud between two rival squires, a mysterious former soldier who may have assumed someone else’s identity, and the difficulty created by Luke Fidelis becoming smitten by the beguiling – but apparently mistreated – wife of a choleric and impetuous local landowner.

Titus Cragg with his wife and child have retreated from Preston to escape the ravages of a viral illness which has claimed the lives of many infants. They have fetched up in a rented house in Accrington, then little more than a scattering of houses beside a stream. Cragg is drawn into the investigation of how it was that Anne Gargrave died at the hands of her fellow villagers, but his work is complicated by a feud between two rival squires, a mysterious former soldier who may have assumed someone else’s identity, and the difficulty created by Luke Fidelis becoming smitten by the beguiling – but apparently mistreated – wife of a choleric and impetuous local landowner. I have to admit to a not-so-guilty-pleasure taken from reading historical crime fiction, and I can say with some certainty that one of the things Robin Blake does so well is the way he handles the dialogue. No-one can know for certain how people in the eighteenth century- or any other era before speech could be recorded – spoke to each other. Formal written or printed sources would be no more a true indication than a legal document would be today, so it is not a matter of scattering a few “thees” and “thous” around. For me, Robin Blake gets it spot on. I can’t say with authority that the way Titus Cragg talks is authentic, but it is convincing and it works beautifully.

I have to admit to a not-so-guilty-pleasure taken from reading historical crime fiction, and I can say with some certainty that one of the things Robin Blake does so well is the way he handles the dialogue. No-one can know for certain how people in the eighteenth century- or any other era before speech could be recorded – spoke to each other. Formal written or printed sources would be no more a true indication than a legal document would be today, so it is not a matter of scattering a few “thees” and “thous” around. For me, Robin Blake gets it spot on. I can’t say with authority that the way Titus Cragg talks is authentic, but it is convincing and it works beautifully.

This, then, is the England of Handel and Hogarth (at least he was English) and the looming threat from the Jacobites north of the border. Author Robin Blake, (left) however resists the easy win of setting his story in the bustle of London. Instead, he takes us to the town of Preston, sitting on the banks of the River Ribble in Lancashire.

This, then, is the England of Handel and Hogarth (at least he was English) and the looming threat from the Jacobites north of the border. Author Robin Blake, (left) however resists the easy win of setting his story in the bustle of London. Instead, he takes us to the town of Preston, sitting on the banks of the River Ribble in Lancashire. The investigations carried out by Cragg and Fidelis reveal a growing schism between the tanners and the wealthy men of property who run the town’s affairs. The leather workers are an inward looking community. This state is mostly driven by the fact that they live and work alongside the noisome waste materials – mostly faeces and urine – which are essential to the tanning process, and therefore most local people literally turn up their noses at the tanners. The burgesses and council-men of Preston, on the other hand, have their eyes on what they believe to be an acre or so of valuable land – ripe for redevelopment – currently occupied by the tannery.

The investigations carried out by Cragg and Fidelis reveal a growing schism between the tanners and the wealthy men of property who run the town’s affairs. The leather workers are an inward looking community. This state is mostly driven by the fact that they live and work alongside the noisome waste materials – mostly faeces and urine – which are essential to the tanning process, and therefore most local people literally turn up their noses at the tanners. The burgesses and council-men of Preston, on the other hand, have their eyes on what they believe to be an acre or so of valuable land – ripe for redevelopment – currently occupied by the tannery.