If Betjeman was the poet of joyful nostalgia, Philip Larkin inhabited a much darker universe. He was born in Coventry in 1922, and after attending King Henry VIII school went on to Oxford to read English. There, he began to write poetry and became friends with KIngsley Amis who shared Larkin’s love of jazz, which he was to write about as jazz critic for The Daily Telegraph. He was an ardent traditionalist and loved Bessie Smith, Bix Beiderbeck and Louis Armstrong, but had little time for what he saw as the the more self-obsessed music of modern players like John Coltrane.

After graduating, Larkin became a librarian, first in Shropshire, then Leicester, Belfast and, finally at the University of Hull in 1955. He was to remain there for the rest of his life, and he took the job extremely seriously and was responsible for overseeing and encouraging the growth of the collection and buildings, and was regarded as an excellent administrator.

His first collection of poems was published in 1945 under the title The North Ship. The poem of the title is very different in tone and structure from more familiar works of later years.

Larkin takes the traditional Christmas carol and adds a more sombre note with the enigmatic fate of the third ship, “rigged for a long journey”. It was ten years before his second collection of poems, The Less Deceived was published. The twenty nine poems included Church Going, where he rubbed shoulders with John Betjeman, but in a darker and – perhaps – more disturbing – way.

Once I am sure there’s nothing going on

I step inside, letting the door thus shut.

Another church: matting, seats, and stone,

And little books; sprawlings of flowers, cut

For Sunday, brownish now; some brass

Up at the holy end; the small neat organ;

And a tense, musty, unignorable silence,

Brewed God knows how long.

Hatless, I take off My cycle clips in awkward reverence.

He wonders if the nondescript church is worth stopping for, but then reflects on what the building has meant to generations of people, and he wonders how long the place will remain central to the lives of people nearby, or if it has already outlived any use it may have had:

Yet stop I did: in fact I often do,

And always end much at a loss like this,

Wondering what to look for; wondering, too,

When churches will fall completely out of use

What we shall turn them into, if we shall keep

A few cathedrals chronically on show,

Their parchment, plate and pyx in locked cases,

And let the rest rent free to rain and sheep.

Shall we avoid them as unlucky places?

Here, he presages a sentiment expressed in one of his more celebrated later poems, Going, Going (1972)

For the first time I feel somehow

That it isn’t going to last,

That before I snuff it, the whole

Boiling will be bricked in

Except for the tourist parts –

First slum of Europe: a role

It won’t be hard to win,

With a cast of crooks and tarts.

And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

There’ll be books; it will linger on

In galleries; but all that remains

For us will be concrete and tyres.

By this time Larkin had completely found his voice, and while his early work showed something of the lyrical intensity of Yeats, the gentle pessimism and sense of regret found in Thomas Hardy was embedded in everything he wrote. There are differences. Hardy’s novels look back to the rural communities he knew – or was told about – in the 1850s, while his poems often reflect on his troubled relationship with his first wife, Emma Gifford. So what does Larkin regret? In what is one of his most celebrated poems, This Be The Verse, he seems to blame his parents, despite his early years being notable for the absence of obvious neglect or cruelty. The crucial four words are “they may not mean to”:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

Larkin’s poems, although often misanthropic, are not without humour. In Annus Mirabilis he pokes sly fun at the sexual revolution. He also echoes Betjeman’s love of what we might call product placement – the use of brand names to evoke a period atmosphere that would ring the bells of readers of a certain age:

Sexual intercourse Began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me)

Between the end of the “Chatterly” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP

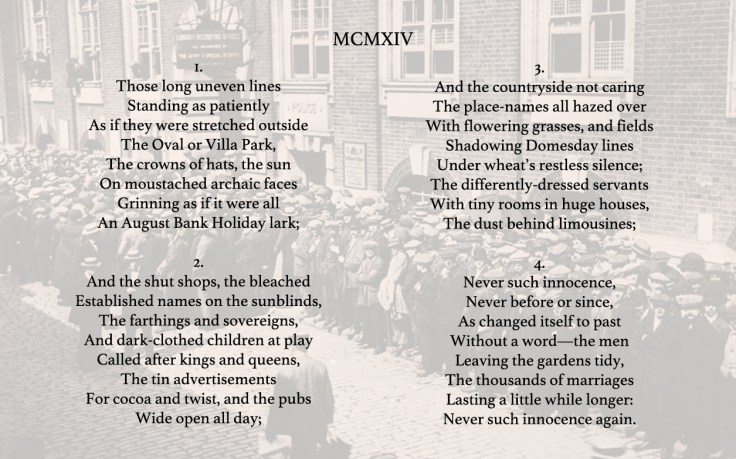

Larkin’s genius and his sheer Englishness is nowhere better expressed than in MCMXIV which was published as part of his 1964 collection The Whitsun Weddings. Larkin grew up at a time when there were still tens of thousands of survivors from The Great War across the country and even by the 1960s they still marched on Armistice Sunday. He contrasts the bustling masculinity of sporting venues with the timeless nature of the ancient rural landscape, and makes the telling observation that the men in the “long uneven lines” staring out from old photographs were more than just from a bygone age – the “moustached archaic faces” might have been from another universe. His comment on the bitter and catastrophic effects of the coming slaughter on families couldn’t be more eloquent – “The thousands of marriages Lasting a little while longer.” The shattering of the established social order and the death of the Edwardian dream remain a constant theme in Great War literature, but the last four words of this poem encapsulate it with such a depth of sadness.

It has been asserted, in recent times, that Larkin was not the kindest of people, had a misogynistic streak in him, and was not destined to fit the stringent requirements imposed on us all by modern sensibilites about race and gender. It is not my place to apologise to people he may have treated badly, but I can only say that when creative people mine down into the complex geology of humanity, they rarely emerge with clean hands. For me, at any rate, his consummate poetry and what it tells us about the human condition completely diminishes any failings he may have had as a person.

I’ll start with Tennyson, but offer a word of caution. Look hard at his poetry and you may not see obvious indicators of his Lincolnshire roots. But let me turn it on its head. Visit the village of Somersby, an isolated and lonely hamlet deep in the Wolds of Lincolnshire, the place where he spent his boyhood. His father was rector of the church (above), and he would have wandered the isolated lanes thereabouts as a boy. The streams, the rustic bridges, the grand old houses still exist, and are little different from when he knew them. The walled garden in

I’ll start with Tennyson, but offer a word of caution. Look hard at his poetry and you may not see obvious indicators of his Lincolnshire roots. But let me turn it on its head. Visit the village of Somersby, an isolated and lonely hamlet deep in the Wolds of Lincolnshire, the place where he spent his boyhood. His father was rector of the church (above), and he would have wandered the isolated lanes thereabouts as a boy. The streams, the rustic bridges, the grand old houses still exist, and are little different from when he knew them. The walled garden in