No fictional character has been so imitated, transposed to another century, Steampunked, turned into an American, or subject to pastiche than Sherlock Holmes. In my late teens I became aware of a series of stories by Adrian Conan Doyle (the author’s youngest son) and I thought they were rather good. Back then, I was completely unaware that the Sherlock Holmes ‘industry’ was running even while new canonical stories were still being published in the 1890s. Few of them survive inspection, and I have to say I am a Holmes purist. I watched one episode of Benedict Cumberbatch’s ‘Sherlock’, and then it was dead to me. As for Robert Downey Jr, don’t (as they say)”get me started.” For me, the film/TV apotheosis was Jeremy Brett, but I have a warm place in my heart for the 1950s radio versions starring Carleton Hobbs and Norman Shelley.

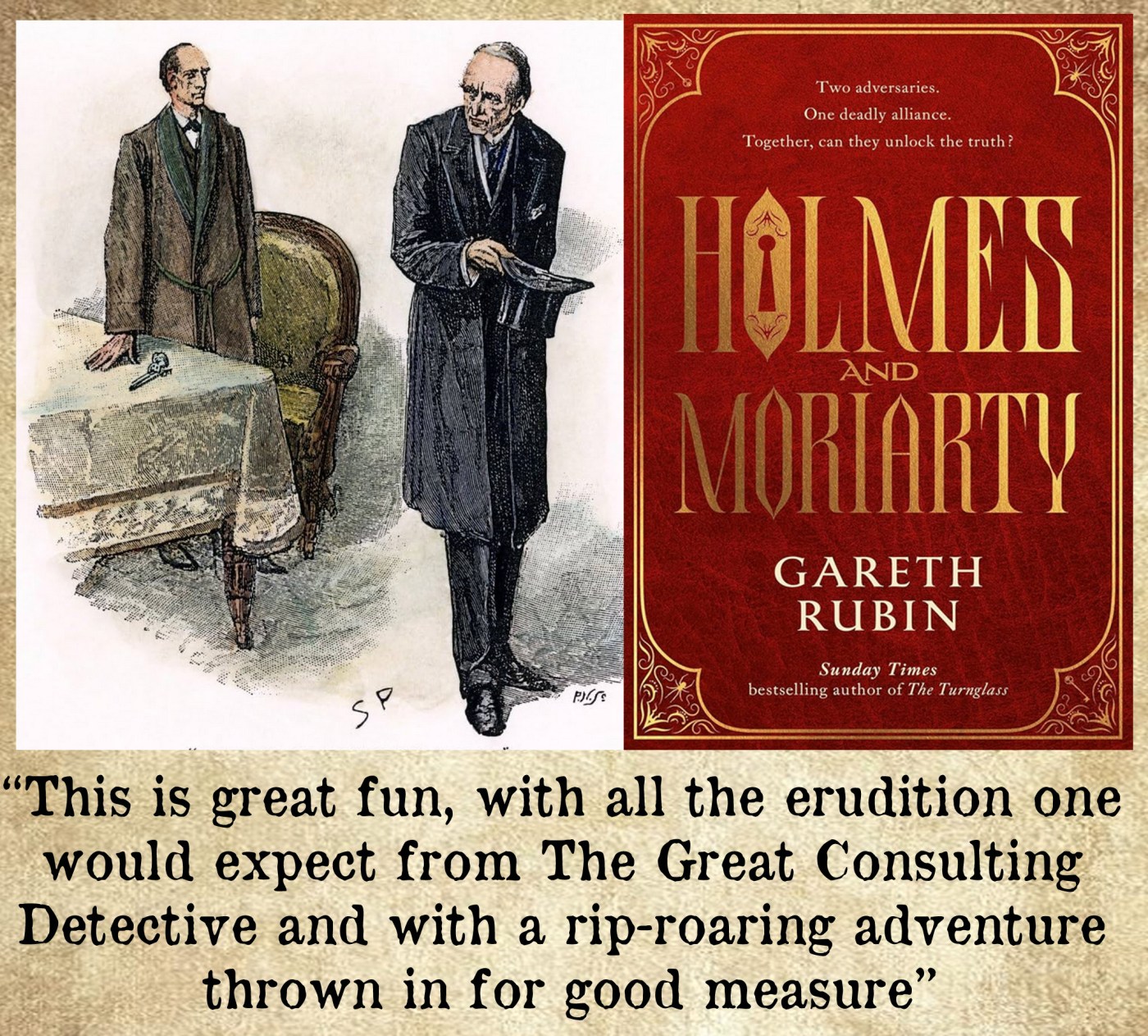

How, then, how does this latest manifestation of The Great Man hold up? The narrative has a pleasing symmetry. The good Doctor is, as ever, the storyteller, but as the book title suggests there is another element. Alternate chapters are seen through the eyes of a man called Moran who is, if you like, Moriarty’s Watson. Gareth Rubin’s Watson is pretty much the standard loyal friend, stalwart and brave, if slightly slow on the uptake. Moran’s voice is suitably different, peppered with criminal slang and much more racy.

The case that draws Holmes into action is rather like The Red Headed League, in that a seemingly odd but ostensibly harmless occurrence (a red haired man being employed to copy out pages of an encyclopaedia) is actually cover for something far more sinister. In this case, a young actor has been hired to play Richard III in a touring production. He comes to Holmes because he is convinced that the small audiences attending each production are actually the same people each night, but disguised differently each time.

Meanwhile, Moriarty has become involved in a turf war involving rival gangsters, and there is an impressive body count, mostly due to the use of a terrifying new invention, the Maxim Gun. There is so much going on, in terms of plot strands, that I would be here all week trying to explain but, cutting to the chase, our two mortal enemies are drawn together after a formal opening of an exhibition at The British Museum goes spectacularly wrong when two principal guests are killed by a biblical plague of peucetia viridans. Google it or, if you are an arachnophobe, best give it a miss.

Long story short, three of the men who led the archaeological dig that produced the exhibits for the aborted exhibition at the BM are now dead, killed in some sort of international conspiracy. It is worth reminding readers that as the 19thC rolled into the 20thC, the pot that eventually boiled over in 1914 was already simmering. Serbian nationalism, German territorial ambitions, the ailing empires of the Ottomans and Austria Hungary, and the gathering crisis in Russia all made for a toxic mix. This novel is not what I would call serious historical fiction. It is more of a melodramatic – and very entertaining – romp, and none the worse for that, but Gareth Rubin makes us aware of the real-life dangerous times inhabited by his imaginary characters.

Eventually Holmes, Watson, Moriarty and Moran head for Switzerland as uneasy allies, for it is in these mountains that the peril lurks, the conspiracy of powerful men that threatens to change the face of Europe. They fetch up in Grenden, a strange village in the shadow of the Jungfrau and it is here, in a remarkably palatial hotel given the location, they are sure they have come to the place from which the plot will be launched. By this stage the novel has taken a distinctly Indiana Jones turn, with secret passages, and deadly traps (again involving spiders).

This is great fun, with all the erudition one would expect from The Great Consulting Detective and with a rip-roaring adventure thrown in for good measure. It is published by Simon & Schuster, and will be available at the end of September.

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

We are in London in the summer of 1879, and young Holmes has yet to meet the man who will write up his greatest cases. Holmes works for a guinea a day, and is striving to build his reputation. Within the first few pages, he has been hired to investigate two cases on behalf of a man who was already a celebrity, and another who would become infamous in his lifetime, but revered and admired after his death. The celebrity is Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, a notorious Lothario whose battleground has been country houses and mansions the length and breadth of the country, the vanquished being a long list of cuckolded husbands. It seems that the heir to the throne has been in the habit of entering his sexual achievements in a diary – a kind of fornicator’s Bradshaw, if you will – but it has gone missing, and Holmes is charged with recovering it.

We are in London in the summer of 1879, and young Holmes has yet to meet the man who will write up his greatest cases. Holmes works for a guinea a day, and is striving to build his reputation. Within the first few pages, he has been hired to investigate two cases on behalf of a man who was already a celebrity, and another who would become infamous in his lifetime, but revered and admired after his death. The celebrity is Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, a notorious Lothario whose battleground has been country houses and mansions the length and breadth of the country, the vanquished being a long list of cuckolded husbands. It seems that the heir to the throne has been in the habit of entering his sexual achievements in a diary – a kind of fornicator’s Bradshaw, if you will – but it has gone missing, and Holmes is charged with recovering it. One hundred pages in, and it is clear that the author is enjoying a glorious exercise in name-dropping. James McNeill Whistler, Lillie Langtry, Francis Knollys, Patsy Cornwallis-West, Frank Miles, Sarah Bernhardt, John Everett Millais and Rosa Corder (right) are just a few of the real life characters who make an appearance, and it is clear that ‘Sherlock Holmes’ moves in very elegant circles.

One hundred pages in, and it is clear that the author is enjoying a glorious exercise in name-dropping. James McNeill Whistler, Lillie Langtry, Francis Knollys, Patsy Cornwallis-West, Frank Miles, Sarah Bernhardt, John Everett Millais and Rosa Corder (right) are just a few of the real life characters who make an appearance, and it is clear that ‘Sherlock Holmes’ moves in very elegant circles.