This enjoyable police procedural novel is the sixth in the series (to read reviews of the previous two, click this link) following the career of Norfolk copper Detective Chief Inspector Greg Geldard, his girlfriend Detective Sergeant Chris Mathews, and the rest of their team. These novels pretty much follow on from each other, and in the previous book Geldard battled a violent Lithuanian gangster called Constantin Gabrys. Now, it’s March 2020, Gabrys is serving a long prison sentence and his psychotic son is dead. However, all is not well, because a key figure in the case, now under witness protection has been attacked. He survived, but a police officer has been seriously injured, and it is obvious that the leak of information can only have come from within the police forced itself.

Despite the Gabrys empire having been apparently dismantled, their poisonous legacy hangs over Norfolk like a miasma. Norfolk, I hear you ask? Surely not that wonderful holiday destination with its abundant wildlife, historic homes and beautiful coastline? While the entire county might not be a wretched hive of scum and villainy, there are places – like Yarmouth and Gorleston – which suffer deep deprivation, and are consequently ripe feeding grounds for organised criminals, whether imported from Eastern Europe or of the home-grown variety.

Geldard traces the leak to a civilian police secretarial worker, but is dismayed to learn that part of the conspiracy involves Helen Gabrys, a member of the family he thought to have been as innocent of wrong doing as she was disgusted at her father’s career.

You will notice in the first paragraph that the story is set in March 2020. Remember that? As the country begins to shut down against the ravages of Covid, life just gets more difficult for Geldard and his team. Right across the criminal justice system things are starting to unravel. Court backlogs become years rather than months, prisons are struggling with absent staff, and the police themselves have to try to hold important conversations yards apart from each other. As the cover blurb suggests, however, the streets may be nearly empty, but evil is just as happy within four walls as out in public places.

There is a parallel thread in the story, which I found unsettling and hard to read. In Yarmouth live the Mirren family. Children Karen and Jake don’t have the happiest lives. Their mum is well-meaning, but weak, and browbeaten by her brutish husband. Karen has a place where she feels valued, can be herself and feel comfortable with trusted adults. It is her primary school, and when it shuts, forcing all the children to stay at home, it is a life sentence for the little girl. The reason this part of the novel affected me is that I taught in Norfolk for over thirty years, and for the latter part of that I led Safeguarding, and the scenes that Heather Peck describes were uncomfortably familiar.

When tragedy strikes in the Mirren house, the subsequent events become very much the concern of Greg Geldard, and he has to add a significant missing persons search to his mounting caseload. In the best traditions of great Victorian writers like Dickens and Hardy, who serialised their novels in popular magazines prior to publishing them in their entirety, Heather Peck leaves us on a knife edge, eagerly awaiting the next novel in this impressive series. Beyond Closed Doors was published by Ormesby Publishing on 22nd June.

This is the fourth book in a series featuring Norfolk copper DCI Greg Geldard, but author Heather Peck (left) wastes no time in providing all the back-story we need. Geldard is divorced from his former wife, Isabelle, who is a professional singer. She has now remarried a celebrated orchestral conductor, with whom she has a child, while Geldard is in a relationship with one of his colleagues, DS Chris Mathews. When he gets an early morning ‘phone call from Isabelle saying she and her son have been threatened by a foreign criminal connected to one of Geldard’s previous cases, he is forced to stay at arm’s length, but is disturbed to hear from a colleague that Isabelle may be making the story up.

This is the fourth book in a series featuring Norfolk copper DCI Greg Geldard, but author Heather Peck (left) wastes no time in providing all the back-story we need. Geldard is divorced from his former wife, Isabelle, who is a professional singer. She has now remarried a celebrated orchestral conductor, with whom she has a child, while Geldard is in a relationship with one of his colleagues, DS Chris Mathews. When he gets an early morning ‘phone call from Isabelle saying she and her son have been threatened by a foreign criminal connected to one of Geldard’s previous cases, he is forced to stay at arm’s length, but is disturbed to hear from a colleague that Isabelle may be making the story up.

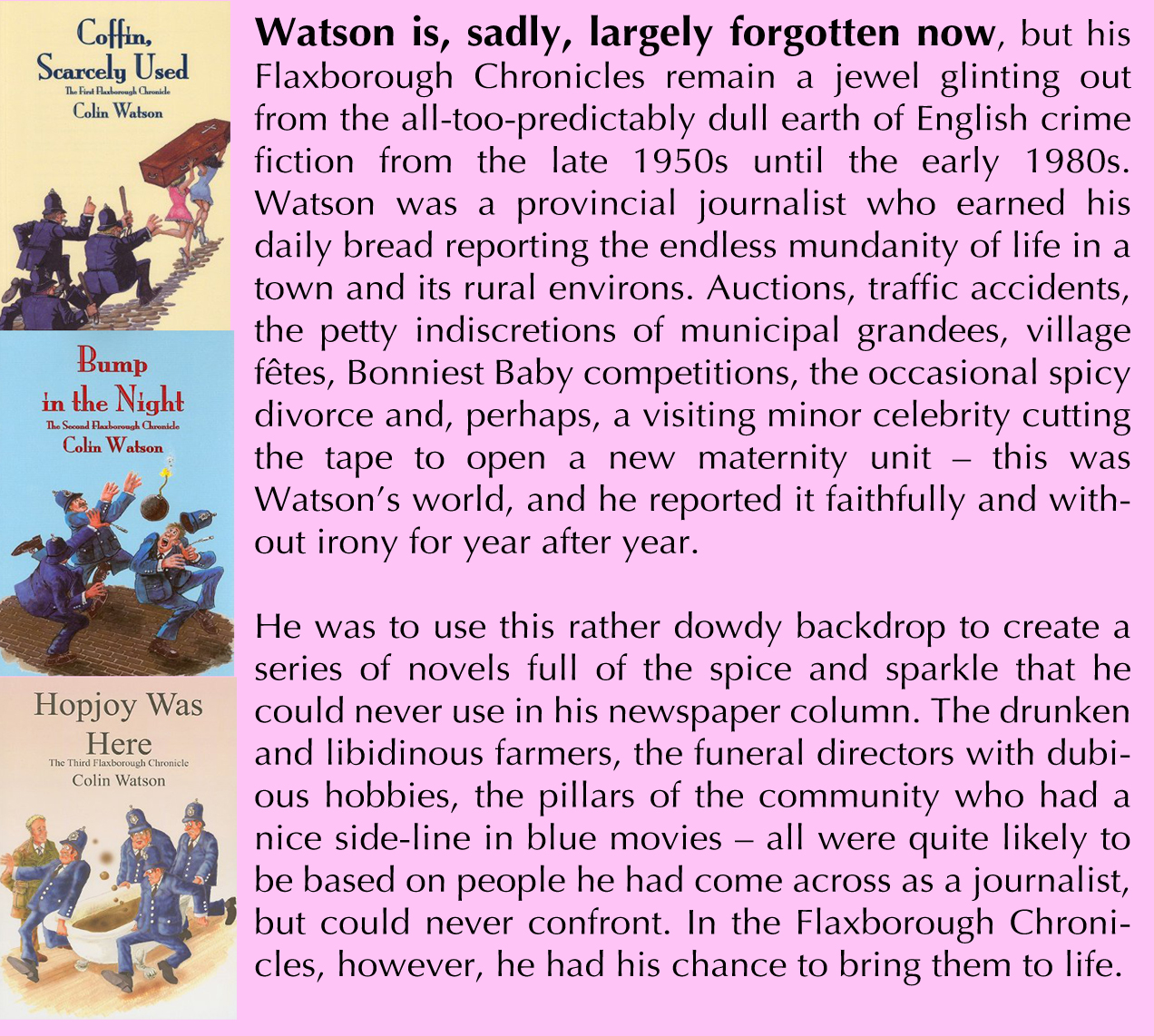

The next stage of our journey is to a town that doesn’t exist – at least on an Ordance Survey map. Writers have always created fictional towns based on real places – think Thomas Hardy’s Casterbridge, Trollope’s Barchester, Arnold Bennett’s Bursley, Herriot’s Darrowby, and Dylan Thomas’s Llareggub – but remember that each was based on a real life place well known to the writer. Thus we drive along a road that skirts the windswept and muddy shores of The Wash until we arrive in Boston, Lincolnshire. It was here that the journalist and writer Colin Watson lived and worked for many years, and it was in Boston’s image that he created Flaxborough – the home and jurisdiction of Inspector Walter Purbright.

The next stage of our journey is to a town that doesn’t exist – at least on an Ordance Survey map. Writers have always created fictional towns based on real places – think Thomas Hardy’s Casterbridge, Trollope’s Barchester, Arnold Bennett’s Bursley, Herriot’s Darrowby, and Dylan Thomas’s Llareggub – but remember that each was based on a real life place well known to the writer. Thus we drive along a road that skirts the windswept and muddy shores of The Wash until we arrive in Boston, Lincolnshire. It was here that the journalist and writer Colin Watson lived and worked for many years, and it was in Boston’s image that he created Flaxborough – the home and jurisdiction of Inspector Walter Purbright.

Here on the coast of The Wash we can, if we wish, still measure the seasons by produce. I say “if we wish”, because supermarkets have no seasons – everything is available all the year round. But in the old fashioned world of buying food when it is fresh and local, the year has its own rhythm. Early summer gives us asparagus, followed by strawberries. In autumn and winter Brancaster mussels and native oysters are delicious, but for me, the true treasure of the summer months is samphire. This plant of the coastal marshes, Crithmum maritimum, allegedly gets its name from a corruption of the French “St Pierre”, but whatever its etymology, it is utterly delicious. Lightly boiled or steamed, it is best eaten with the fingers. Running the stems through your teeth to strip off the flesh is a completely sybaritic sensation. Local folk love it with vinegar, but with butter and coarsely ground pepper it is little short of heavenly.

Here on the coast of The Wash we can, if we wish, still measure the seasons by produce. I say “if we wish”, because supermarkets have no seasons – everything is available all the year round. But in the old fashioned world of buying food when it is fresh and local, the year has its own rhythm. Early summer gives us asparagus, followed by strawberries. In autumn and winter Brancaster mussels and native oysters are delicious, but for me, the true treasure of the summer months is samphire. This plant of the coastal marshes, Crithmum maritimum, allegedly gets its name from a corruption of the French “St Pierre”, but whatever its etymology, it is utterly delicious. Lightly boiled or steamed, it is best eaten with the fingers. Running the stems through your teeth to strip off the flesh is a completely sybaritic sensation. Local folk love it with vinegar, but with butter and coarsely ground pepper it is little short of heavenly. Shaw and George Valentine series with At Death’s Window. In addition to solving a series of burglaries at properties along the Norfolk coast owned by wealthy out-of-towners, Shaw and Valentine become involved in a turf war between product dealers. These are not your common-or-garden drug barons, or even owners of ice cream vans, but dealers in samphire! As I have illustrated, with a 300% mark-up available for an item that can be had for nothing, why bother with something as illegal and potentially lethal as narcotics? The problem in At Death’s Window comes when local folk are muscled off their home territory by criminal gangs using illegal immigrants as pickers. Think cockles and the Morecambe Bay tragedy, and you can see how it all might go pear-shaped.

Shaw and George Valentine series with At Death’s Window. In addition to solving a series of burglaries at properties along the Norfolk coast owned by wealthy out-of-towners, Shaw and Valentine become involved in a turf war between product dealers. These are not your common-or-garden drug barons, or even owners of ice cream vans, but dealers in samphire! As I have illustrated, with a 300% mark-up available for an item that can be had for nothing, why bother with something as illegal and potentially lethal as narcotics? The problem in At Death’s Window comes when local folk are muscled off their home territory by criminal gangs using illegal immigrants as pickers. Think cockles and the Morecambe Bay tragedy, and you can see how it all might go pear-shaped.