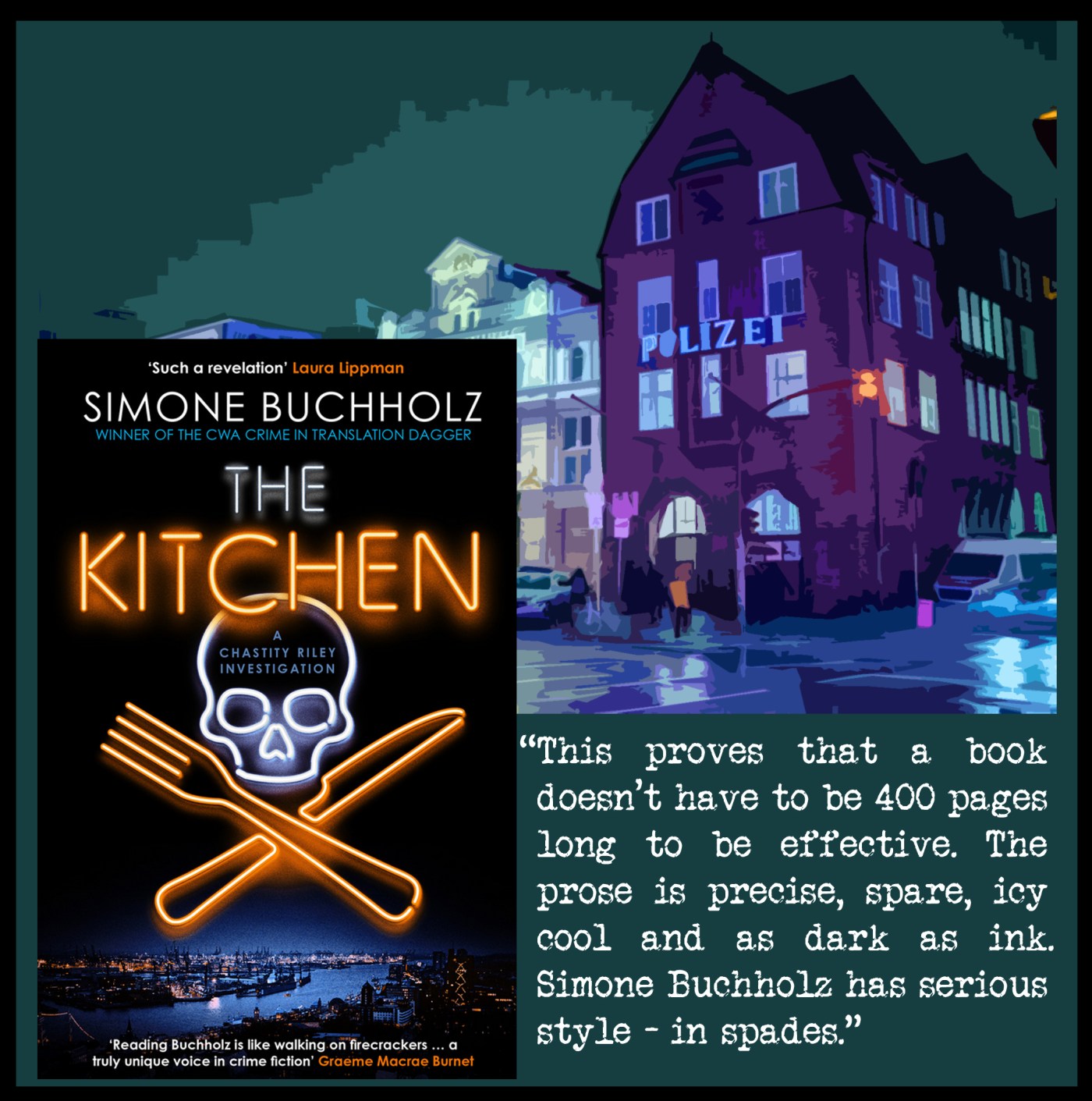

As her name suggests, Hamburg State Prosecutor Chastity Riley has American antecedents, but her work and life are both firmly centred in the German city that sits astride the River Elbe. Author Simone Buchholz leaves us pretty much to our own devices to imagine what she looks like, but we know she smokes, enjoys a drink or three, can be foul-mouthed, and has an on-off relationship with a chap called Klatsche.

From the word go, Buchholz drops a broad hint about what is going on, but Riley only finds out much later. Her immediate problem is that two packages of body parts have been recovered from the Elbe, disturbed by dredging. The men have – literally – been expertly butchered and the parts neatly wrapped up in plastic and duct tape. It turns out that the dead men have a history of serious abuse towards women, and a witness report suggests that two women are linked to the killings.

A third body is found, this one being intact, but Riley has another problem to solve. She has a friend named Carla, who runs a coffee shop and is a very important part of Riley’s life, fulfilling the dual function of sister and mother. When Carla is attacked and raped by two men, Riley becomes angry with the police’s apparent lack of urgency, but is powerless to intervene. As well as trying to solve the mystery of the Elbe packages she is central in a current court case where two people traffickers are on trial. Their business model was to travel to rural areas in places like Romania, and persuade young women that a glamorous lifestyle awaits them in Germany. The reverse is true, of course, and the girls are soon put to work in Hamburg’s notorious sex trade.

Events in Riley’s personal and professional life seek to be spinning out of control. First, thanks to the defence lawyers in the trafficking case successfully making out that their clients are really nice chaps who had traumatic childhoods, and who’ve just had a bit of bad luck recently, the smirking criminals get the lightest sentence possible. Then, she and Klatsche discover that Carla – with the assistance of a shady friend called Rocco – have done what the police failed to do, and have captured the two rapists. It is only with the greatest reluctance that Riley realises she must persuade Carla to hand the two men over to the police.

When, with a mixture of instinct and sheer luck, Riley identifies the two women responsible for the three earlier murders, her professional integrity is put to its sternest test. In some ways this is a very angry book and is centred on the evil that men do, particularly to women. It is obviously entirely appropriate to the tone of the book that much of it is set in the St Pauli district of Hamburg, an area that began its notoriety centuries ago as a place that provided entertainment for sailors. Its infamous Reeperbahn remains a living – and sadly prosperous – example of women being made into a commodity to please men. Despite her obvious anger, however, Buchholz (left) doesn’t moralise. Chastity Riley realises that Hamburg is what it is, and if the needle of her moral compass occasionally swings in an unexpected direction, then so be it.

The Kitchen proves that a book doesn’t have to be 400 pages long to be effective. The prose is precise, spare, icy cool and as dark as ink. Simone Buchholz has serious style – in spades. The book was translated by Rachel Ward, published by Orenda Books and is available now.

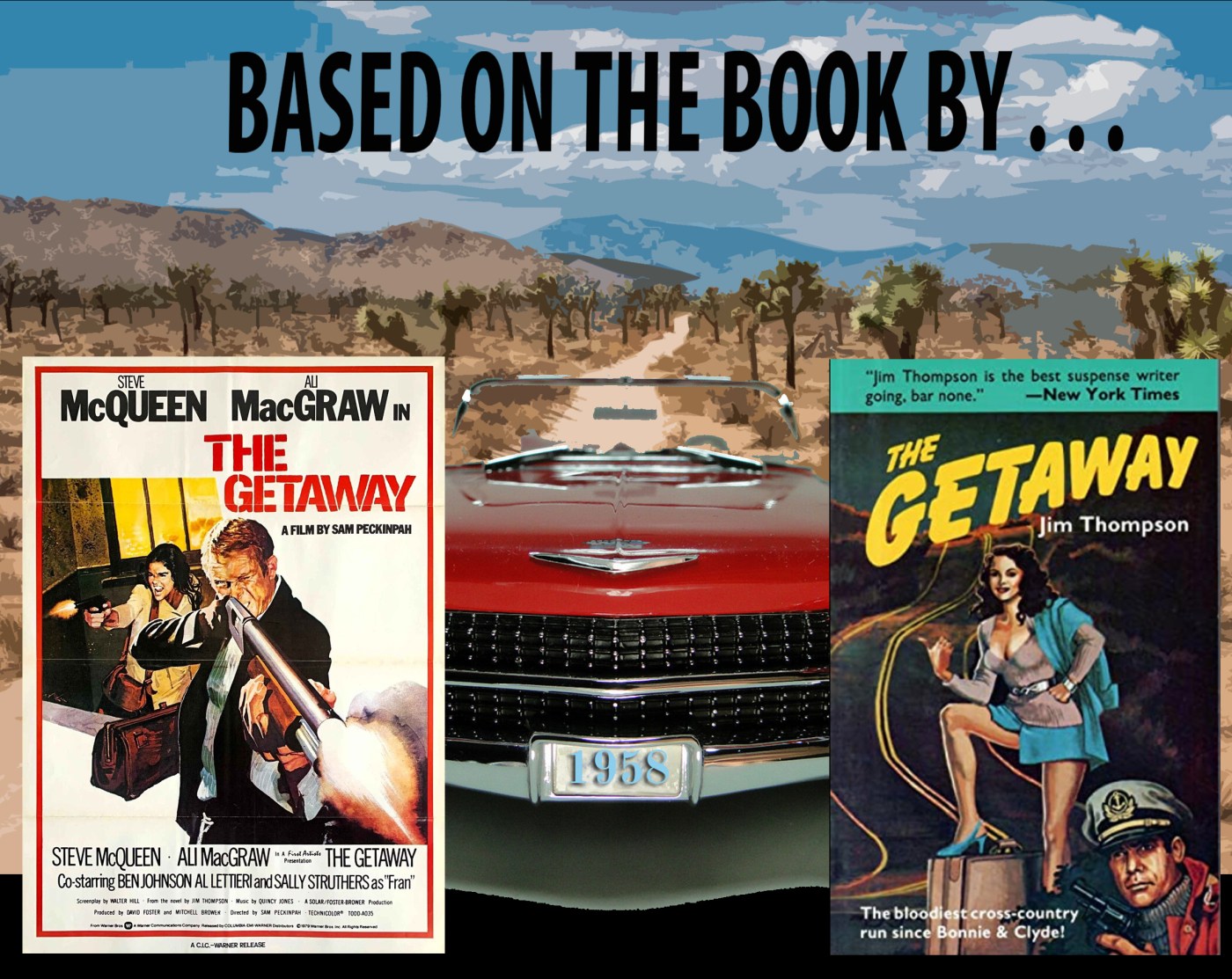

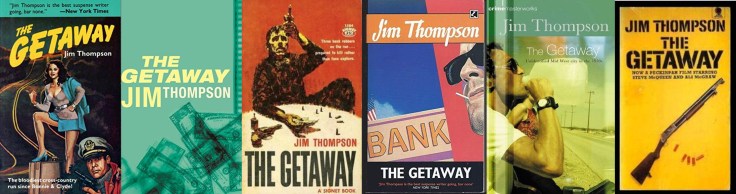

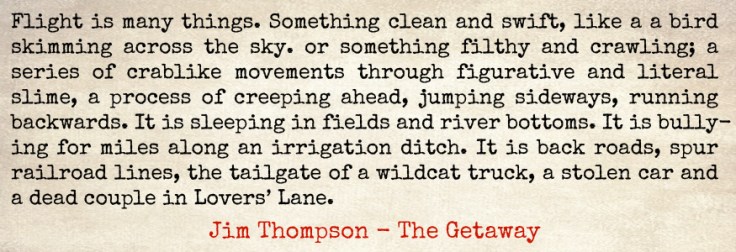

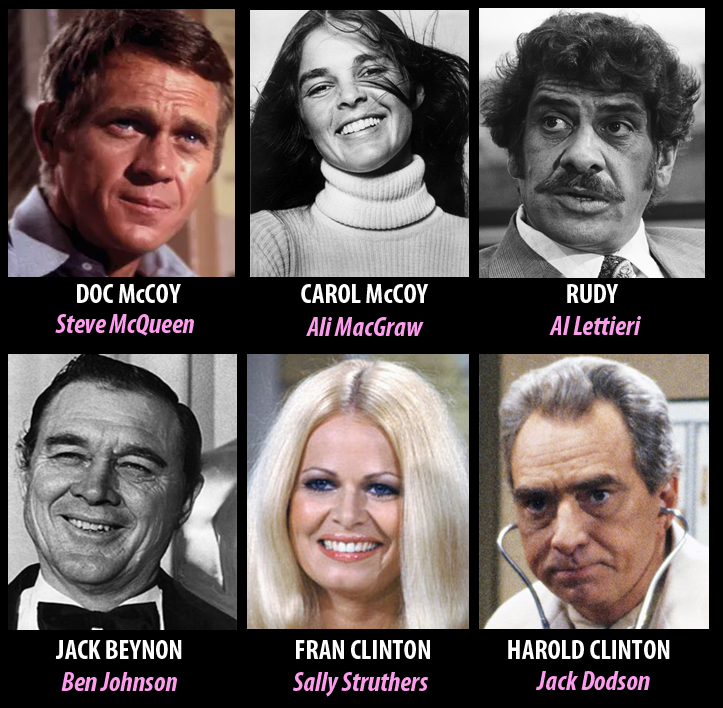

The 1972 film, (trailer above) directed by Sam Peckinpah with a screenplay (eventually) by Walter Hill was ‘wrong’ from the word go, at least in terms of the book. It is hardly surprising that Jim Thompson (right) hired to write the screenplay, didn’t last long on the project and was sacked. Star man was Hollywood golden boy Steve McQueen. With box office hits like The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963) Bullitt (1968) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) on his resumé, he wasn’t ever going to be right for the homicidal and totally amoral Doc McCoy. The producers were probably of the mindset that they had the star, so to hell with the book. The film Doc McCoy is a criminal for sure, but he doesn’t murder people. He’s a Robin Hood or a (film version) Clyde Barrow. Beynon is the villain of the piece, and Rudy is working for him. This was the cast:

The 1972 film, (trailer above) directed by Sam Peckinpah with a screenplay (eventually) by Walter Hill was ‘wrong’ from the word go, at least in terms of the book. It is hardly surprising that Jim Thompson (right) hired to write the screenplay, didn’t last long on the project and was sacked. Star man was Hollywood golden boy Steve McQueen. With box office hits like The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963) Bullitt (1968) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) on his resumé, he wasn’t ever going to be right for the homicidal and totally amoral Doc McCoy. The producers were probably of the mindset that they had the star, so to hell with the book. The film Doc McCoy is a criminal for sure, but he doesn’t murder people. He’s a Robin Hood or a (film version) Clyde Barrow. Beynon is the villain of the piece, and Rudy is working for him. This was the cast:

We soon learn, however, in the novel, that McCoy is a ruthless and stone cold killer. Rudy Tarrento is a monster, but he has something of an excuse. He is insane. Doc, though, is – by all interpretations – perfectly rational and in good mental health. In the film, after much ammunition is expended in various shoot-outs, Doc and Carol buy an old truck from a cowboy (played by the legendary Slim Pickens – left) and – almost literally – drive off into the Mexican sunset, full of life and love, with most of the loot intact. The ending of the novel is – to put it mildly – enigmatic. It has the feel of an hallucination. According to Steven King:

We soon learn, however, in the novel, that McCoy is a ruthless and stone cold killer. Rudy Tarrento is a monster, but he has something of an excuse. He is insane. Doc, though, is – by all interpretations – perfectly rational and in good mental health. In the film, after much ammunition is expended in various shoot-outs, Doc and Carol buy an old truck from a cowboy (played by the legendary Slim Pickens – left) and – almost literally – drive off into the Mexican sunset, full of life and love, with most of the loot intact. The ending of the novel is – to put it mildly – enigmatic. It has the feel of an hallucination. According to Steven King:

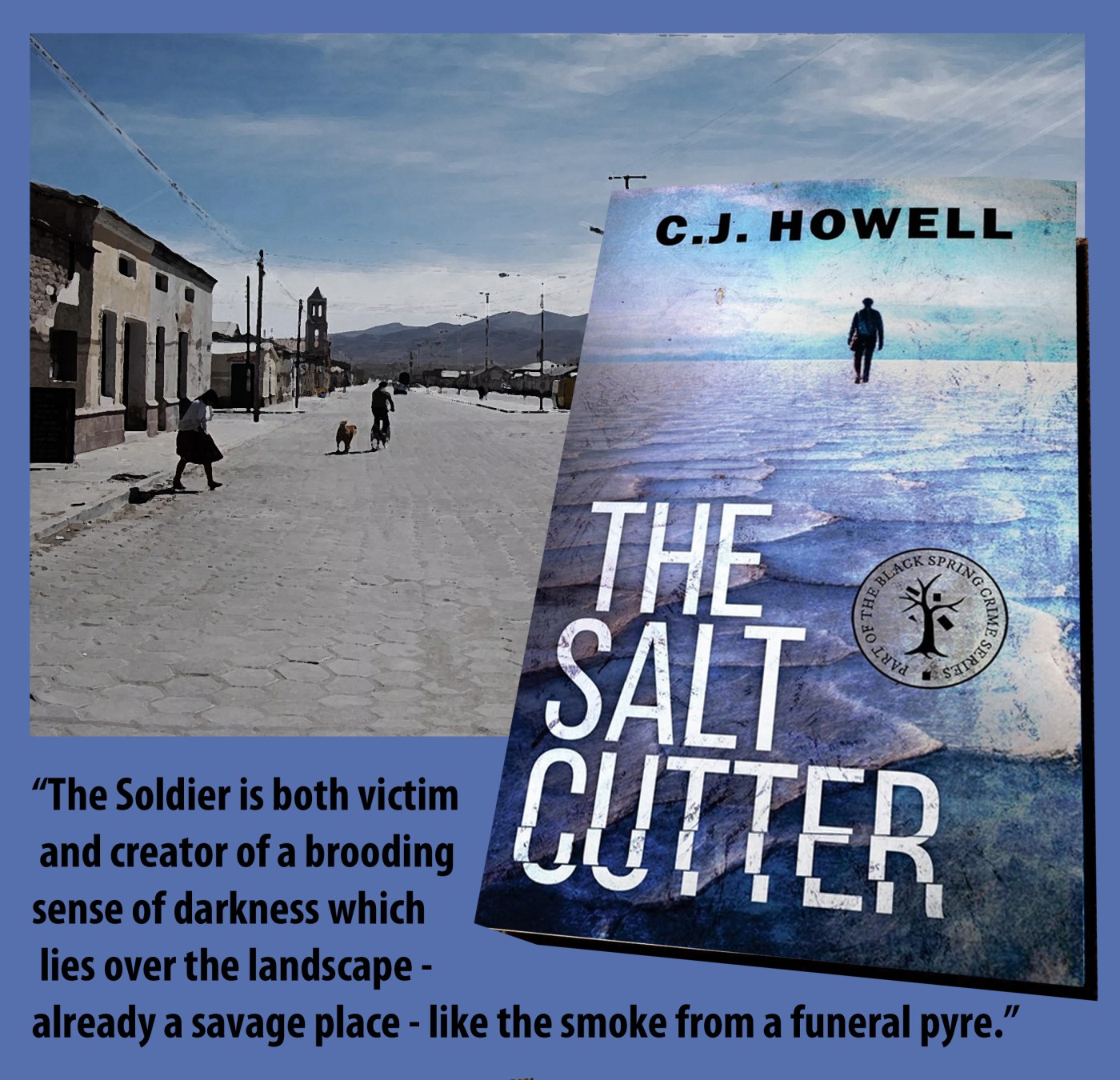

Ask ten different readers what they think qualifies as ‘noir’ and you will get ten different answers. Is it that everything is framed in a 1950s monochrome? Is it because all the participants behave badly towards each other, and have zero respect for themselves? Is it because we know that when we turn the final page, there will be no outcome that could be described as optimistic or redemptive? One quality, for me, has to be an unremitting sense of bleakness – both physical and moral – and this novel by CJ Howell (left) certainly has that.

Ask ten different readers what they think qualifies as ‘noir’ and you will get ten different answers. Is it that everything is framed in a 1950s monochrome? Is it because all the participants behave badly towards each other, and have zero respect for themselves? Is it because we know that when we turn the final page, there will be no outcome that could be described as optimistic or redemptive? One quality, for me, has to be an unremitting sense of bleakness – both physical and moral – and this novel by CJ Howell (left) certainly has that.

Alfred Edward Lewis was born in Stretford, Manchester on 15th January 1940, but in 1946 the family moved to Barton upon Humber. Five years later, Lewis passed his 11+ and began attending the town’s grammar school. There, he was fortunate enough to come under the influence of an English teacher called Henry Treece. Treece was born in Staffordshire, but had moved to Lincolnshire in 1939, and although he ‘did his bit’ as an RAF intelligence officer, he was able to make his name during the war years as a poet.

Alfred Edward Lewis was born in Stretford, Manchester on 15th January 1940, but in 1946 the family moved to Barton upon Humber. Five years later, Lewis passed his 11+ and began attending the town’s grammar school. There, he was fortunate enough to come under the influence of an English teacher called Henry Treece. Treece was born in Staffordshire, but had moved to Lincolnshire in 1939, and although he ‘did his bit’ as an RAF intelligence officer, he was able to make his name during the war years as a poet. After leaving the college, it seemed that Lewis was going to make his way as an artist and illustrator, and a book written by Alan Delgado, variously called The Hot Water Bottle Mystery or The Very Hot Water Bottle, can be had these days for not very much money, and the description on seller sites usually adds “Illustrated by Edward Lewis”. That was the first serious money Ted ever made. He moved to London in the early 1960s to further his prospects.

After leaving the college, it seemed that Lewis was going to make his way as an artist and illustrator, and a book written by Alan Delgado, variously called The Hot Water Bottle Mystery or The Very Hot Water Bottle, can be had these days for not very much money, and the description on seller sites usually adds “Illustrated by Edward Lewis”. That was the first serious money Ted ever made. He moved to London in the early 1960s to further his prospects. His first published novel was All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965) and it is a semi-autobiographical account of the lives and loves of art students in Hull. I remember borrowing it from the local library not long after it came out and, looking back, it was a far cry from the novels that would make Lewis’s fame and fortune.

His first published novel was All the Way Home and All the Night Through (1965) and it is a semi-autobiographical account of the lives and loves of art students in Hull. I remember borrowing it from the local library not long after it came out and, looking back, it was a far cry from the novels that would make Lewis’s fame and fortune.  of the finest British films ever made. It was released in March 1970, and Lewis is credited, along with director Mike Hodges, with the screenplay. Incidentally, a hardback first edition of JRH can be yours – a snip at just £3,250 (admittedly with a hand-written note by the author)

of the finest British films ever made. It was released in March 1970, and Lewis is credited, along with director Mike Hodges, with the screenplay. Incidentally, a hardback first edition of JRH can be yours – a snip at just £3,250 (admittedly with a hand-written note by the author) believe to be his finest was GBH, published in 1980. Here, he unequivocally returns to Lincolnshire, and a bleak and down-beat out-of-season seaside town which is obviously Mablethorpe. The central character is George Fowler, a mobster who has made a living out of distributing porn movies, but has crossed the wrong people, and needs somewhere to hide up for a while. Rather like his creator, Fowler is in the darkest of dark places, and the novel ends in brutal and surreal fashion on a deserted Lincolnshire beach, with the wind howling in from the north sea as Fowler meets his maker in the remains of an RAF bombing target.

believe to be his finest was GBH, published in 1980. Here, he unequivocally returns to Lincolnshire, and a bleak and down-beat out-of-season seaside town which is obviously Mablethorpe. The central character is George Fowler, a mobster who has made a living out of distributing porn movies, but has crossed the wrong people, and needs somewhere to hide up for a while. Rather like his creator, Fowler is in the darkest of dark places, and the novel ends in brutal and surreal fashion on a deserted Lincolnshire beach, with the wind howling in from the north sea as Fowler meets his maker in the remains of an RAF bombing target.

The Big Sleep was published in 1939, but the iconic film version, directed by Howard Hawks, wasn’t released until 1946. Are the dates significant? There is an obvious conclusion, in terms of what took place in between, but I am not sure if it is the correct one. The novel introduced Philip Marlowe to the reading public and, my goodness, what an introduction. The second chapter, where Los Angeles PI Marlowe goes to meet the ailing General Sternwood who is worried about his errant daughters, contains astonishing prose. Sternwood sits, wheelchair-bound, in what we Brits call a greenhouse. Marlowe sweats as Sternwood tells him:

The Big Sleep was published in 1939, but the iconic film version, directed by Howard Hawks, wasn’t released until 1946. Are the dates significant? There is an obvious conclusion, in terms of what took place in between, but I am not sure if it is the correct one. The novel introduced Philip Marlowe to the reading public and, my goodness, what an introduction. The second chapter, where Los Angeles PI Marlowe goes to meet the ailing General Sternwood who is worried about his errant daughters, contains astonishing prose. Sternwood sits, wheelchair-bound, in what we Brits call a greenhouse. Marlowe sweats as Sternwood tells him:

The book began with an optimistic Marlowe:

The book began with an optimistic Marlowe:

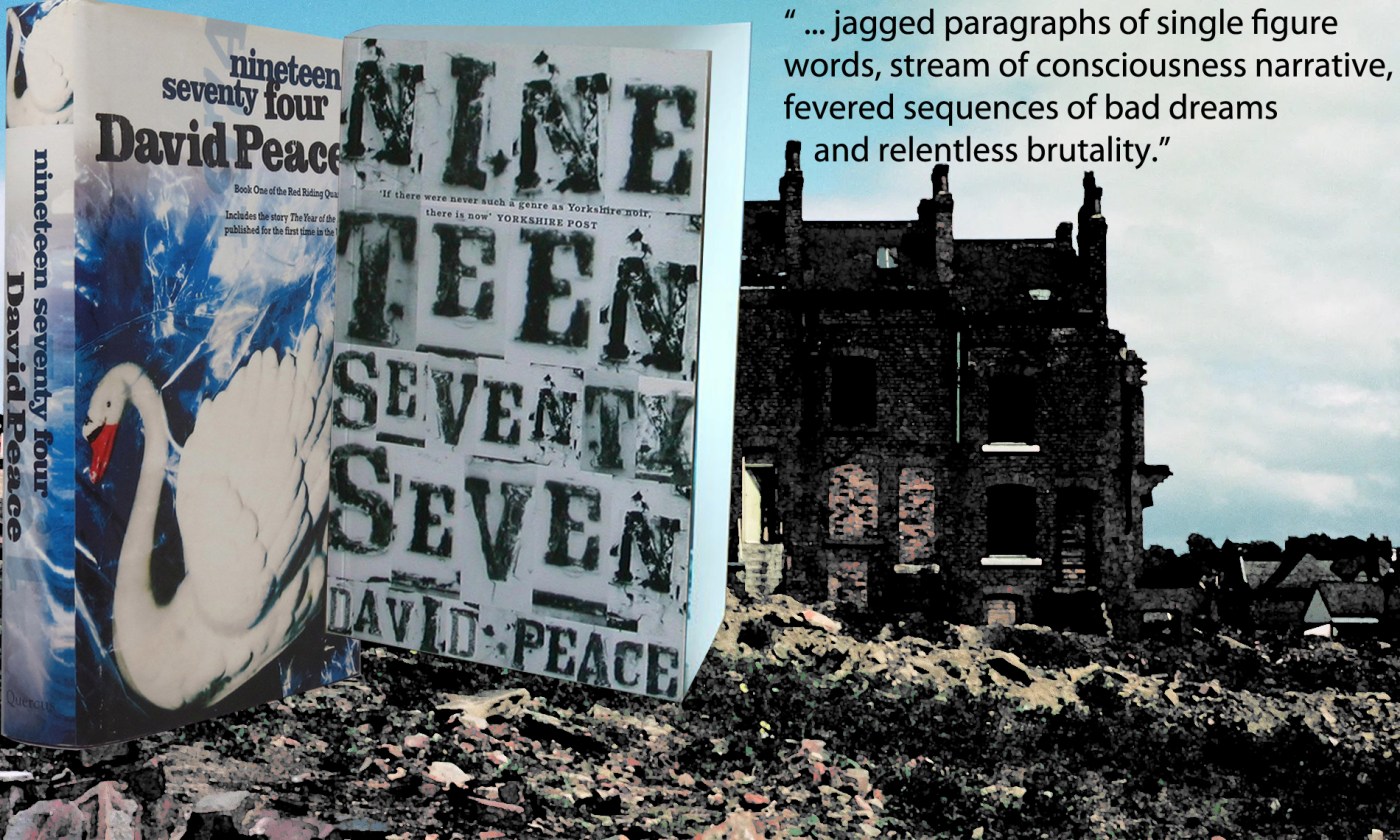

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence.

1974 was praised at the time – and still is – for its coruscating honesty and brutal depiction of a corrupt police force, bent businessmen who have, via brown envelopes, local councillors at their beck and call in a city riven by prostitution, racism and casual violence.