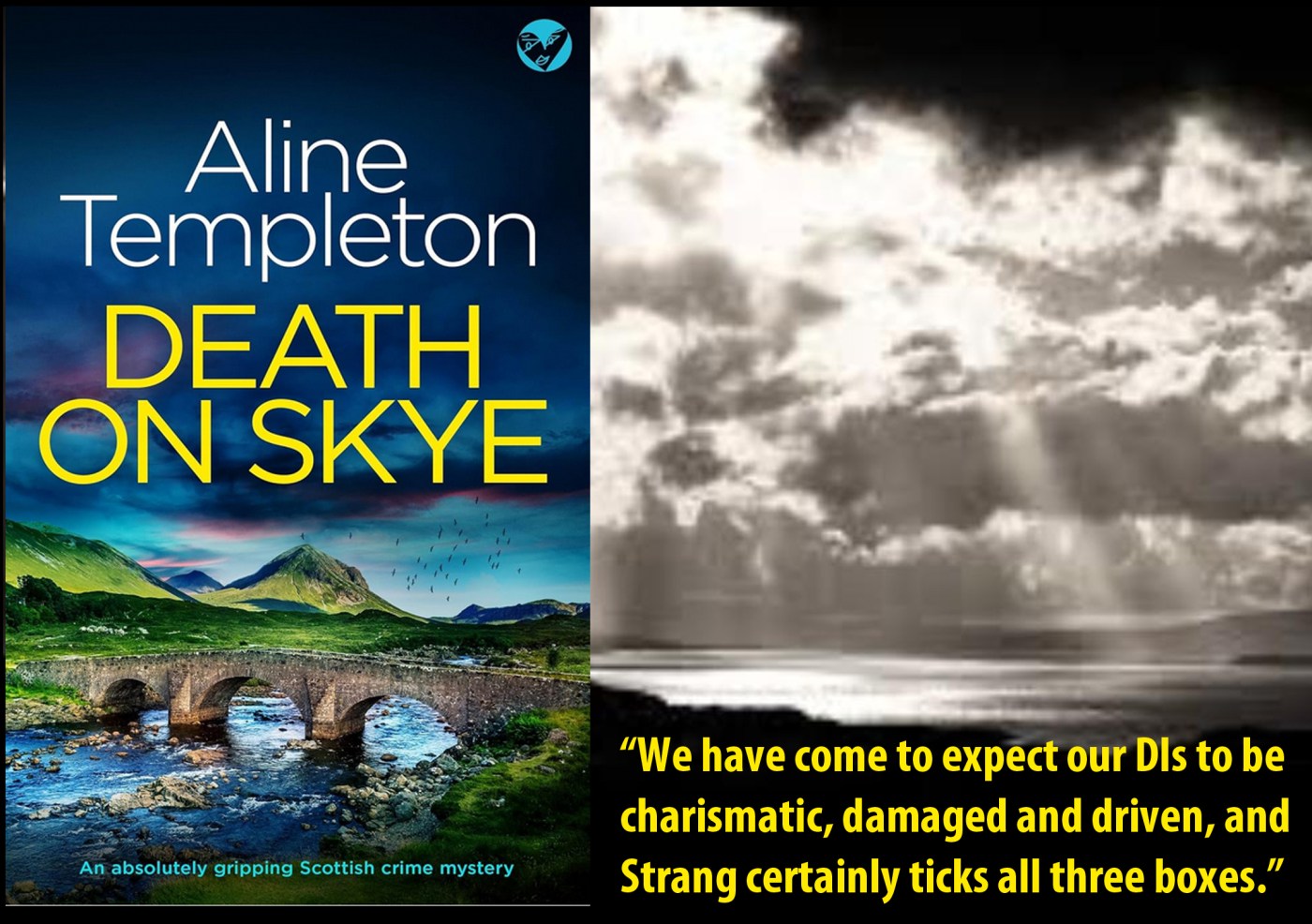

Aline Templeton sets up her stage with admirable directness, and wastes no time introducing us to the characters in her drama. Human Face is (or purports to be) a refugee charity. It has relocated from the south of England to a gloomy Victorian property on Skye and its director, Adam Carnegie is, we soon learn, a wrong ‘un. Beatrice Lacey, a wealthy but emotionally needy supporter of Human Face, had allowed her Surrey home to be used by the charity and is uneasy in its new location, but is in thrall to the messianic Carnegie.

A young woman called Eve is the latest in a series of ‘housekeepers’ at Balnashiel Lodge, and had been promised a British National Insurance number if she behaves herself. Vicky Macdonald, despite marrying a local man, is still regarded as a Sassenach. She does the actual housekeeping at the Lodge.

PC Livvy Murray has been exiled to Skye after being duped by a childhood friend who had been leading a double life in in serious crime. Now, she is stuck in a damp and draughty police house, with her career more or less over before it has started. Kelso Strang is a recently bereaved Edinburgh police officer. He is ex-military, and the son of a Major General. His decision to become a copper has resulted in a huge rift between him and his father.

When Eve is reported missing, Livvy Murray can find nothing suspicious, but refers the matter to her bosses on the mainland. Strang’s boss, seeking to divert him from the trauma of the recent death of his wife in a road accident, sends him up to Skye to investigate.

Aline Templeton has a certain amount of wicked fun at the expense of the unfortunate Beatrice, with her plastic pretend baby, the industrial quantities of chocolate bars she has stashed at strategic points throughout the lodge, and her desperate gullibility. Almost exactly half way through the book, the narrative (which has been ambling along pleasantly enough) explodes into violence, and takes an unexpected turn.

This is the first of a six book series, with an unusual publishing history. All six have appeared between the date of this, 25th August 2025, and the sixth – Death on The Black Isle – on 25th November 2025. Joffe Publishing clearly has a strategy, and I hope it works for them, but is this book any good? Short answer is yes, it’s very readable. The Skye setting is suitably bleak and tempestuous, and the description of the charity scammers rings all too true in a world where ostensibly reputable charities pay obscene amounts of donors’ money to their executives and their TV advertisers.

Were one to summon all the fictional British Detective Inspectors to a convention, the meeting pace would need to be very spacious, and the catering arrangements complex, so does Kelso Strang have sharp enough elbows to make a space for himself? Again, yes. We have come to expect our DIs to be charismatic, damaged and driven, and Strang certainly ticks all three boxes. Death On Skye is available now.

consists of two first person accounts of events, that of Marsi and that of Stina. This, of course, raises the technical dilemma of Stina’s account. Because she is telling us what is happening in the winter 0f 1967, are we to assume that she is still alive? It is not quite such a conundrum as that of Schrödinger’s Cat but, outside the realm of supernatural fiction, the dead cannot speak.

consists of two first person accounts of events, that of Marsi and that of Stina. This, of course, raises the technical dilemma of Stina’s account. Because she is telling us what is happening in the winter 0f 1967, are we to assume that she is still alive? It is not quite such a conundrum as that of Schrödinger’s Cat but, outside the realm of supernatural fiction, the dead cannot speak.

I have to confess that the crime fiction obsession with Scandi crime a decade ago came and went, as far as I was concerned. Some of it was very good, but to this old cynic it seemed that as long as an author had a few diacritic signs in their name, they were good for a publishing deal. Heresy, I know, but there we are. Back From The Dead is not a Scandi crime novel translated into English. The author (left) was born in Copenhagen, but has lived for many years in London, and she writes in English.

I have to confess that the crime fiction obsession with Scandi crime a decade ago came and went, as far as I was concerned. Some of it was very good, but to this old cynic it seemed that as long as an author had a few diacritic signs in their name, they were good for a publishing deal. Heresy, I know, but there we are. Back From The Dead is not a Scandi crime novel translated into English. The author (left) was born in Copenhagen, but has lived for many years in London, and she writes in English.

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

In 2021 I reviewed an earlier contribution to the Sherlockian canon by Bonnie MacBird (left) –

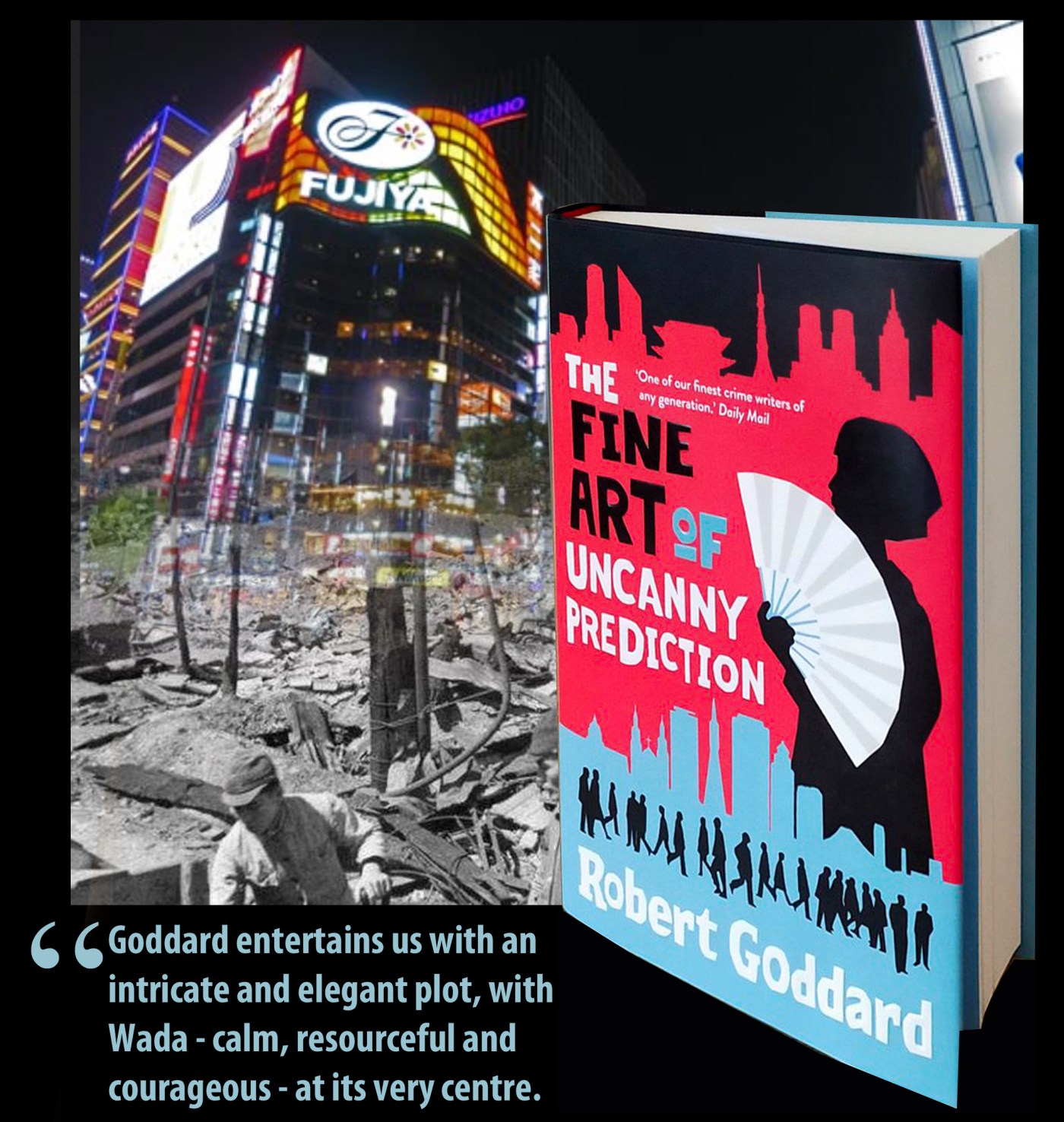

I must confess to not having read anything by Robert Goddard (left) for a few years. Back in the day I enjoyed his James Maxted trilogy, which comprised The Ways of the World (2013), The Corners of the Globe (2014) and The Ends of The Earth (2015), which focused on a young former RAF pilot and his involvement in the political fallout in Europe after the Versailles Conference ended in 1920. I reviewed his standalone novel

I must confess to not having read anything by Robert Goddard (left) for a few years. Back in the day I enjoyed his James Maxted trilogy, which comprised The Ways of the World (2013), The Corners of the Globe (2014) and The Ends of The Earth (2015), which focused on a young former RAF pilot and his involvement in the political fallout in Europe after the Versailles Conference ended in 1920. I reviewed his standalone novel