I absolutely adored Andrew Martin’s Jim Stringer novels from the word go. The Necropolis Railway was set around the actual railway line near Waterloo that took hearse carriages containing the coffins that would be buried in the relatively new Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey, and introduced Jim Stringer, a young railwayman who would join the Railway police, and solve many mysteries, including novels set during Jim’s wartime experience on The Somme, Mesopotamia, and post-war India.

Now, we are in 1925, and Jim is a Detective Inspector based in York. The story is based on a strange encounter Jim had at the York Summer Gala in the summer of that year. He meets his boss, who insists they go and watch one of the attractions – a Wild West Show. They see the usual antics – a fake Red Indian, a ‘gunslinger’ who throws knives at his provocatively dressed female partner, then shoots clay pipes out of her mouth. Both the woman, the Red Indian and the cowboy are about as American as Yorkshire Pudding, but in the audience is a genuine American (who acts as a stooge for the performers, and a celebrated couple in the entertainment business, celebrated film star Cynthia Lorne and her producer husband, Tom Brooks.

The gunslinger, Jack ‘ Kid’ Durrant, is not only good with guns, but has ambitions to writer cowboy novels, rather after the celebrated author of Riders of The Purple Sage, Zane Grey (1872 – 1939) Not only that, the relationship between Lorne, Brooks and himself is, as they say, interesting. When Lorne is found dead, with Brooks and Durrant both missing, it is assumed that Durrant is the killer. Although it is not strictly a matter for the Railway Police, Jim feels personally involved, and visits the place where the three were last seen – the grounds of Bolton Abbey in Wharfedale. This allows Andrew Martin (left) to introduce us to what is known as one of the most dangerous rivers in Europe, The Strid. This natural phenomenon sees the River Wharfe forced through a narrow ravine, just a few feet wide. It has been described as the river ‘running sideways’, rather like a twisted ribbon and is believed to be prodigiously deep. No-one goes into it and ever comes out alive.

The gunslinger, Jack ‘ Kid’ Durrant, is not only good with guns, but has ambitions to writer cowboy novels, rather after the celebrated author of Riders of The Purple Sage, Zane Grey (1872 – 1939) Not only that, the relationship between Lorne, Brooks and himself is, as they say, interesting. When Lorne is found dead, with Brooks and Durrant both missing, it is assumed that Durrant is the killer. Although it is not strictly a matter for the Railway Police, Jim feels personally involved, and visits the place where the three were last seen – the grounds of Bolton Abbey in Wharfedale. This allows Andrew Martin (left) to introduce us to what is known as one of the most dangerous rivers in Europe, The Strid. This natural phenomenon sees the River Wharfe forced through a narrow ravine, just a few feet wide. It has been described as the river ‘running sideways’, rather like a twisted ribbon and is believed to be prodigiously deep. No-one goes into it and ever comes out alive.

The best series are enlivened by recurring subsidiary characters, and one has been ever present in the Jim Stringer novels, in the shape of his wife Lydia. We met her when she was young Jim’s landlady in the first novel. Although understandably distant when Jim was on military duties in France, Mesopotamia and India, she has remained by his side. I am not sure how Martin does it but, without being in the least explicit, he makes her quite the most alluring copper’s wife in detective fiction, and their courtship in The Necropolis Railway was – and you’ll have to read the book to understand the contradiction – chastely erotic.

Central to the appeal is, of course, the heartbreaking descriptions of a railway that we once had, but threw away in various acts of criminal negligence and wrong-headedness. The magnificent smoke and almost animal fury of the engines, the cathedrals that were the stations, the legions of uniformed officials, and the fact that in 1925 you could take a train from almost anywhere to somewhere else with minimal discomfort. All now gone and, in the words of the hymn;

“They fly forgotten, as a dream

Dies at the opening day.”

Jim, of course, tries to get to the bottom of of the mystery, party because – in spite of his devotion to Lydia – he was slightly smitten by the deceased movie star. The melancholy denouement involves a London and North Eastern Railway locomotive,and a definite sense of closure – if not satisfaction – for our man. In one sense, none of this matters, as our total engagement with the pubs, hotels, railway world, social quirks of the 1920s, and the lingering legacy of The Great War has given us that comfortable sensation we feel after feeling sated after a delicious meal. Powder Smoke is published by Corsair and is available now.

Alex Pearl (left) isn’t a reluctant name-dropper, and walk on parts for Julian Clary and Kenneth Clarke (in Ronnie Scott’s, naturally) set the period tone nicely. 1984 was certainly a memorable year. I remember driving through the August night to be at my dying dad’s bedside, and hearing on the radio that Richard Burton had died. Just a few weeks earlier we had been blown away by Farrokh Bulsara at Wembley, while Clive Lloyd and his men were doing something rather similar to the English cricket team.

Alex Pearl (left) isn’t a reluctant name-dropper, and walk on parts for Julian Clary and Kenneth Clarke (in Ronnie Scott’s, naturally) set the period tone nicely. 1984 was certainly a memorable year. I remember driving through the August night to be at my dying dad’s bedside, and hearing on the radio that Richard Burton had died. Just a few weeks earlier we had been blown away by Farrokh Bulsara at Wembley, while Clive Lloyd and his men were doing something rather similar to the English cricket team.

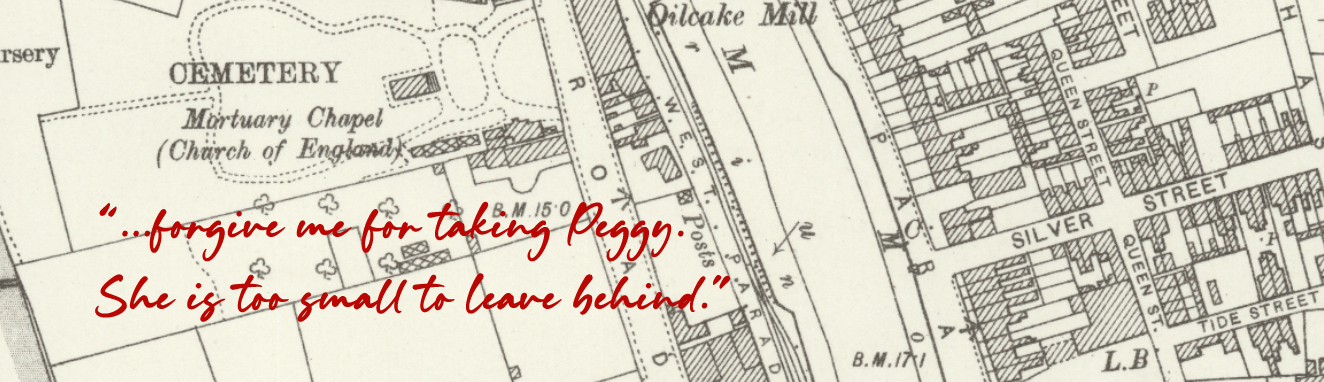

consists of two first person accounts of events, that of Marsi and that of Stina. This, of course, raises the technical dilemma of Stina’s account. Because she is telling us what is happening in the winter 0f 1967, are we to assume that she is still alive? It is not quite such a conundrum as that of Schrödinger’s Cat but, outside the realm of supernatural fiction, the dead cannot speak.

consists of two first person accounts of events, that of Marsi and that of Stina. This, of course, raises the technical dilemma of Stina’s account. Because she is telling us what is happening in the winter 0f 1967, are we to assume that she is still alive? It is not quite such a conundrum as that of Schrödinger’s Cat but, outside the realm of supernatural fiction, the dead cannot speak.