Oh, Blimey, yet another long running series to which I am a stranger. Better late than never, even if I am starting with the nineteenth of the series featuring York copper Geraldine Steel. As a former school teacher (just the forty years at the chalk-face) I can report that in modern schools, a peculiar kind of justice prevails. At the first complaint of serious misbehaviour by a member of staff, said teacher is out on his or her ear – “suspended, pending investigation”. Despite the mealy-mouthed rider that “suspension is not an indication of wrong-doing”, it is plain for all to see that the teacher is guilty until proven innocent. And that is precisely what happens to teacher Paul Moore in Final Term when he falls foul of a rather unpleasant teenager called Cassie Jackson. She claims he has molested her, and he is immediately shown the door, while Cassie’s claim is examined.

Sadly, there is not much time for a thorough investigation, as Cassie’s dead body is found in nearby woodland. The post mortem reveals that she died from a severe blow to the head, she was full of alcohol. There is no sign of recent sexual trauma, but she had undergone an abortion in the last twelve months or so. DI Steel and her team swing into action, but clues are scarce. Cassie’s 18 year-old boyfriend is initially suspected, but his anger at her death seems genuine. The, with the case going nowhere, another girl from the same school is found naked and dead, and the fears deepen that a serial killer may be at large.

When both Paul Moore and his wife Laura are proved to have lied to the police about what they were doing on the night of Cassie’s murder, Geraldine’s boss senses that Moore ticks at least two of the standard boxes in a murder investigation – he had the motive and the opportunity. Geraldine is, however, uneasy about the arrest, as there is nothing forensically to link Moore to the murders. We, too, guess that he didn’t do it, as we meet the real killer about half way through the book. He is, though, rather like those anonymous TV confessions back in the day, merely a silhouette.

With Paul Moore languishing in a police cell, Laura Moore goes missing. Then, Geraldine makes that mistake which is a trope in so many novels and films – she goes off on her own, following a hunch, but telling no-one where she is going. Inevitably, she falls foul of the killer, and with her live-in partner Ian, a fellow copper, heavily involved, the search for the missing women brings Final Term to an exciting conclusion.

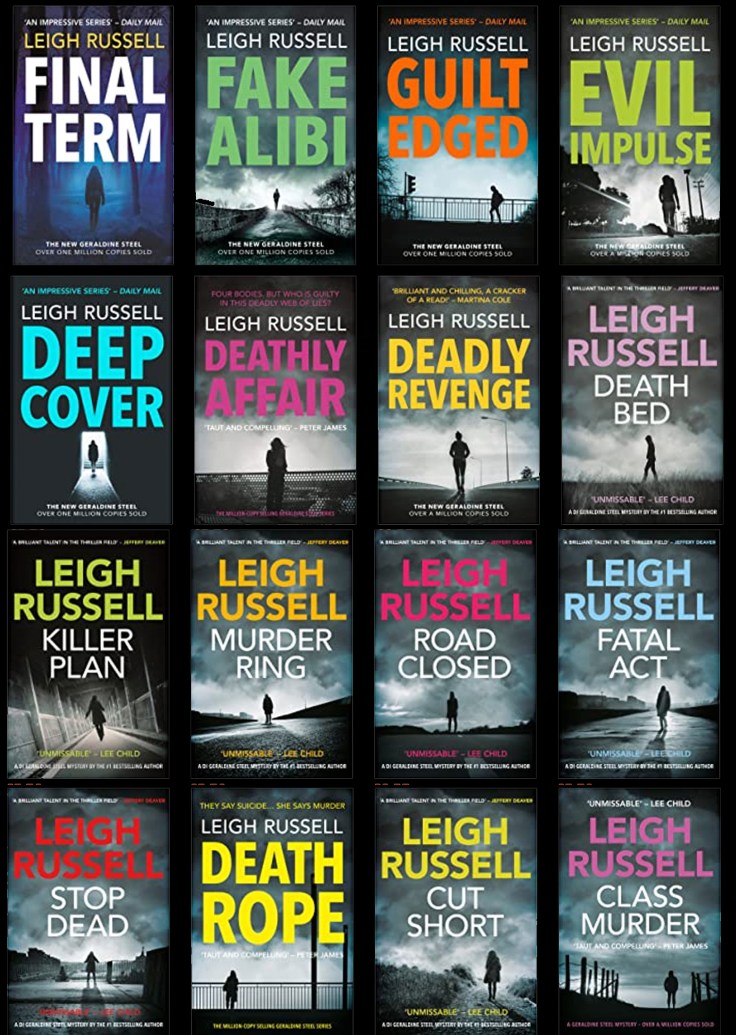

Leigh Russell (right) studied literature at university, and spent four years immersed in books. After that,she became a teacher, a career that enabled her to share her enthusiasm for books with teenagers. For years, she read other people’s books with no plans to write her own, when the idea for a story popped into her mind. Intrigued by a fictitious killer who had arrived, unbidden, to lurk in her imagination, she began to write a story. That story, Cut Short, was shortlisted for a CWA Dagger Award, and went on to become the first in a long running series. She now has three series to her name. Besides DI Geraldine Steel, her other books feature Steel’s sergeant Ian Peterson, and a civilian investigator called Lucy Hall.

Leigh Russell (right) studied literature at university, and spent four years immersed in books. After that,she became a teacher, a career that enabled her to share her enthusiasm for books with teenagers. For years, she read other people’s books with no plans to write her own, when the idea for a story popped into her mind. Intrigued by a fictitious killer who had arrived, unbidden, to lurk in her imagination, she began to write a story. That story, Cut Short, was shortlisted for a CWA Dagger Award, and went on to become the first in a long running series. She now has three series to her name. Besides DI Geraldine Steel, her other books feature Steel’s sergeant Ian Peterson, and a civilian investigator called Lucy Hall.

Just in case anyone should get sniffy and dismiss this – and other books in the series – as “formulaic”, let me ask this. Do you complain about the repetitive structure of the Sherlock Holmes stories? Is it a turn-off that the Nero Wolfe stories always begin with Archie Goodwin presenting a problem to his boss in Wolfe’s apartment?. Are the Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novels unreadable because of the ever present Steve Carella, Cotton Hawes, Bert Kling, Meyer Meyer and Pete Byrnes? I think we all know the answer. If the other eighteen books in this series are anywhere near as good as Final Term, then Leigh Russell has earned her place on the CriFi podium.

Final Term is published by No Exit Press and is on sale now.

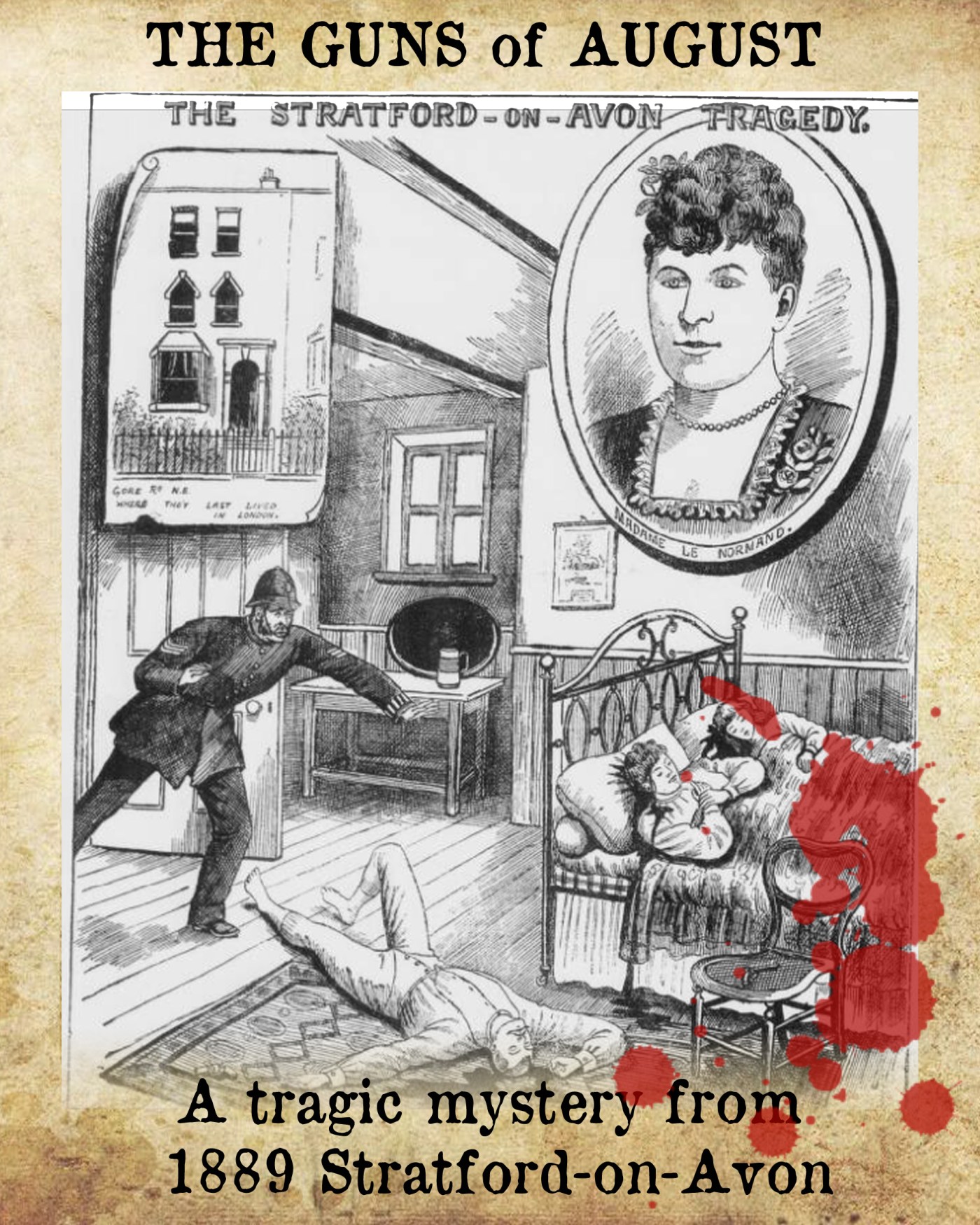

What threw the investigation on its head was the fact that the woman who died in that Stratford cottage was not von Gamsenfels wife, although the dead child was probably his. By examining the dead man’s possessions, the police discovered that his legal wife was a Mrs Rosanna Lachmann von Gamsenfels, and that their marriage was somewhat unusual. He was absent from the family home for months on end, but always gave his wife money for the upkeep of their son. Mrs Lachmann von Gamsenfels traveled up to Stratford to identify her husband’s body, but was either unable- or unwilling – to put names to the dead woman and girl. Try as they may, the authorities were unable to put names to the woman and girl who were shot dead on that fateful Monday morning. Artists’ impressions of ‘Mrs von Gamsenfels” were published (left) but she and her daughter left the world unknown, and if anyone mourned them, they kept silent.

What threw the investigation on its head was the fact that the woman who died in that Stratford cottage was not von Gamsenfels wife, although the dead child was probably his. By examining the dead man’s possessions, the police discovered that his legal wife was a Mrs Rosanna Lachmann von Gamsenfels, and that their marriage was somewhat unusual. He was absent from the family home for months on end, but always gave his wife money for the upkeep of their son. Mrs Lachmann von Gamsenfels traveled up to Stratford to identify her husband’s body, but was either unable- or unwilling – to put names to the dead woman and girl. Try as they may, the authorities were unable to put names to the woman and girl who were shot dead on that fateful Monday morning. Artists’ impressions of ‘Mrs von Gamsenfels” were published (left) but she and her daughter left the world unknown, and if anyone mourned them, they kept silent.

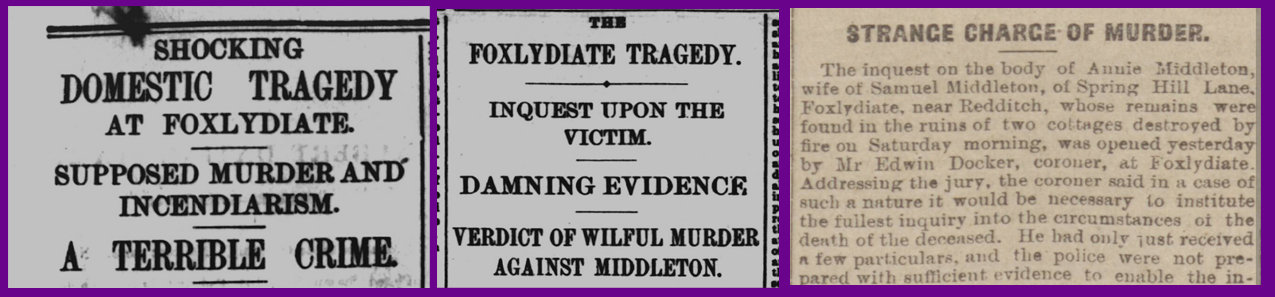

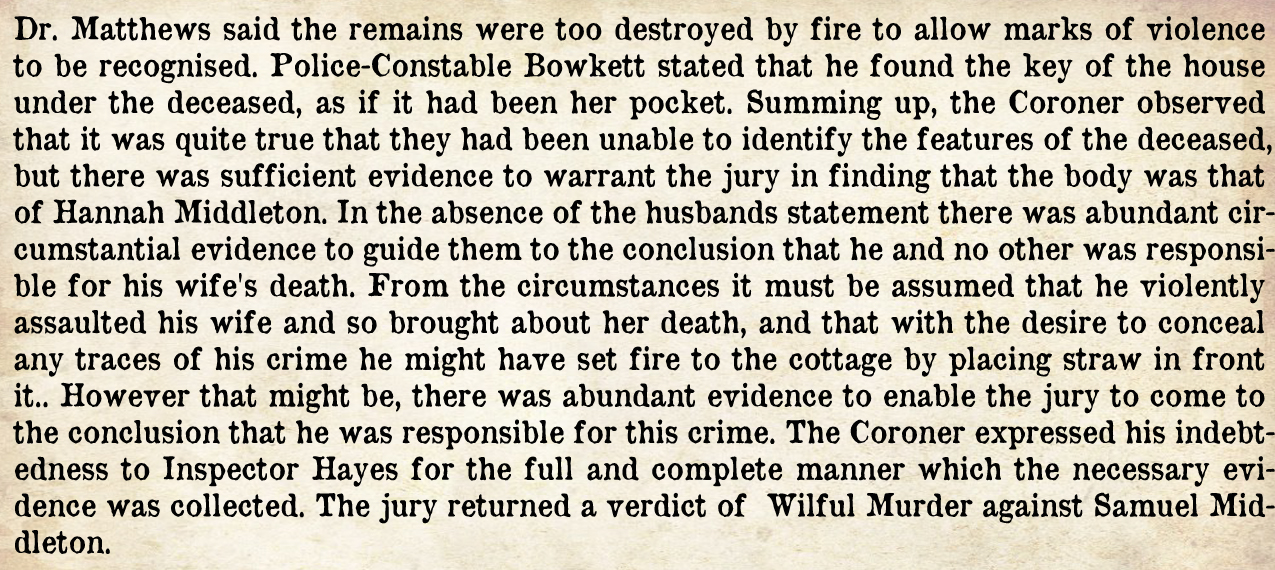

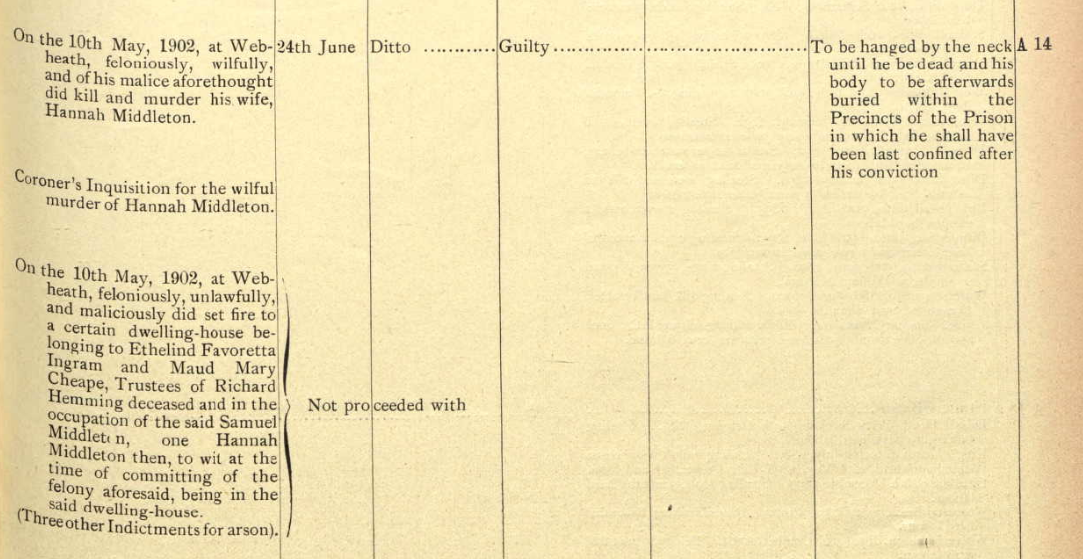

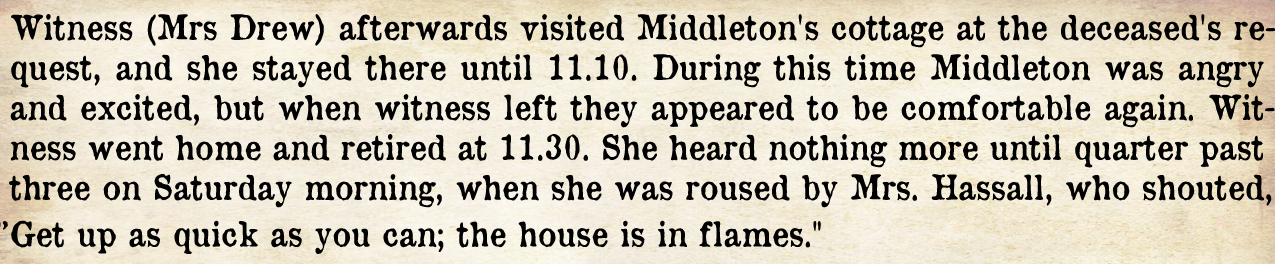

SO FAR: On the evening of 10th/11th May 1902, Foxlydiate couple Samuel and Hannah Middleton had been having a protracted and violent argument. At 3.30 am the alarm was given that their cottage was on fire. When the police were eventually able to enter what was left of the cottage there was little left of Hannah Middleton (left, in a newspaper likeness) but a charred corpse. Samuel Middleton was arrested on suspicion of murdering his wife. The coroner’s inquest heard that one of the technical problems was that Hannah Middleton’s body had been so destroyed by the fire that a proper examination was impossible.

SO FAR: On the evening of 10th/11th May 1902, Foxlydiate couple Samuel and Hannah Middleton had been having a protracted and violent argument. At 3.30 am the alarm was given that their cottage was on fire. When the police were eventually able to enter what was left of the cottage there was little left of Hannah Middleton (left, in a newspaper likeness) but a charred corpse. Samuel Middleton was arrested on suspicion of murdering his wife. The coroner’s inquest heard that one of the technical problems was that Hannah Middleton’s body had been so destroyed by the fire that a proper examination was impossible.

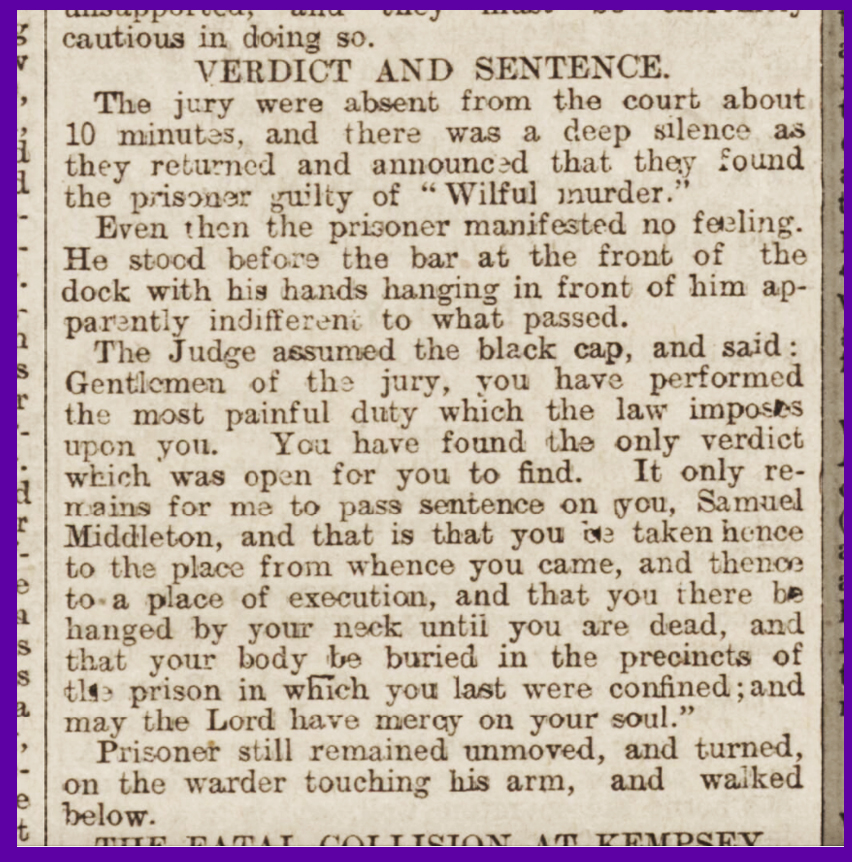

Samuel Middleton was sent for trial at the summer assizes in Worcester. Assize courts were normally held three or four times a year in the county towns around the country, and were presided over by a senior judge. These courts were were for the more serious crimes which could not be dealt with my local magistrate courts. At the end of June, Samuel Middleton stood before Mr Justice Wright (left) and the proceedings were relatively short. The only fragile straw Middleton’s defence barristers could cling to was the lesser charge of manslaughter. Middleton had repeatedly said, in various versions, that his wife had clung to him with the intention of doing him harm – “She would have bit me to pieces, so I had to finish her.” It was clear to both judge and jury, however, that Middleton had battered his wife over the head with a poker, and then set fire to the cottage in an attempt to hide the evidence. Mr Justice Wright delivered the inevitable verdict with due solemnity.

Samuel Middleton was sent for trial at the summer assizes in Worcester. Assize courts were normally held three or four times a year in the county towns around the country, and were presided over by a senior judge. These courts were were for the more serious crimes which could not be dealt with my local magistrate courts. At the end of June, Samuel Middleton stood before Mr Justice Wright (left) and the proceedings were relatively short. The only fragile straw Middleton’s defence barristers could cling to was the lesser charge of manslaughter. Middleton had repeatedly said, in various versions, that his wife had clung to him with the intention of doing him harm – “She would have bit me to pieces, so I had to finish her.” It was clear to both judge and jury, however, that Middleton had battered his wife over the head with a poker, and then set fire to the cottage in an attempt to hide the evidence. Mr Justice Wright delivered the inevitable verdict with due solemnity.

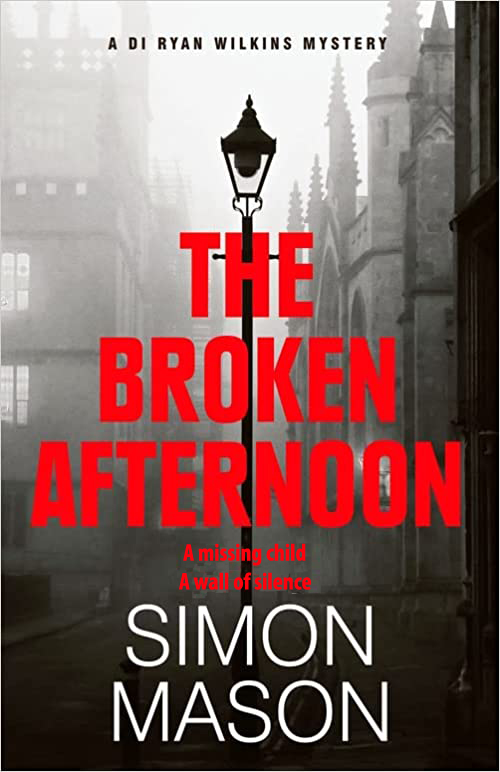

In Simon Mason’s A Killing In November we met Oxford DI Ryan Wilkins, and the book ended with his dismissal from the force for disciplinary reasons. In this book he is still in Oxford, but working as a security guard/general dogsbody at a van hire firm. His former partner, also named Wilkins, but Ray of that ilk, is now heading up the team that was once Ryan’s responsibility, and it is they who are tasked with investigating the abduction of a little girl from her nursery school.

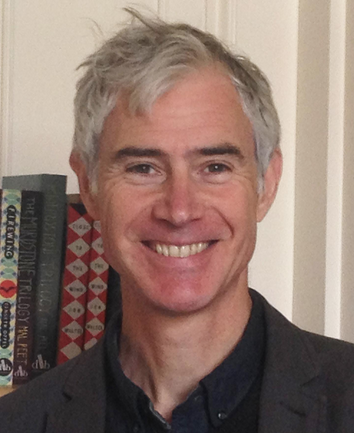

In Simon Mason’s A Killing In November we met Oxford DI Ryan Wilkins, and the book ended with his dismissal from the force for disciplinary reasons. In this book he is still in Oxford, but working as a security guard/general dogsbody at a van hire firm. His former partner, also named Wilkins, but Ray of that ilk, is now heading up the team that was once Ryan’s responsibility, and it is they who are tasked with investigating the abduction of a little girl from her nursery school. I am sorry, but that is not how I see this book. Yes, it is set in and around Oxford, but apart from The Broken Afternoon being every bit as good a read as, say, The Silence of Nicholas Quinn or The Remorseful Day, that’s where the resemblance ends. Mason’s book, while perhaps not being Noir in a Derek Raymond or Ted Lewis way, is full of dark undertones, bleak litter strewn public spaces, and the very real capacity for the police to get things badly, badly wrong. Simon Mason (right) has created coppers who certainly don’t spend melancholy evenings gazing into pints of real ale and then sit home alone listening to Mozart while sipping a decent single malt.

I am sorry, but that is not how I see this book. Yes, it is set in and around Oxford, but apart from The Broken Afternoon being every bit as good a read as, say, The Silence of Nicholas Quinn or The Remorseful Day, that’s where the resemblance ends. Mason’s book, while perhaps not being Noir in a Derek Raymond or Ted Lewis way, is full of dark undertones, bleak litter strewn public spaces, and the very real capacity for the police to get things badly, badly wrong. Simon Mason (right) has created coppers who certainly don’t spend melancholy evenings gazing into pints of real ale and then sit home alone listening to Mozart while sipping a decent single malt.