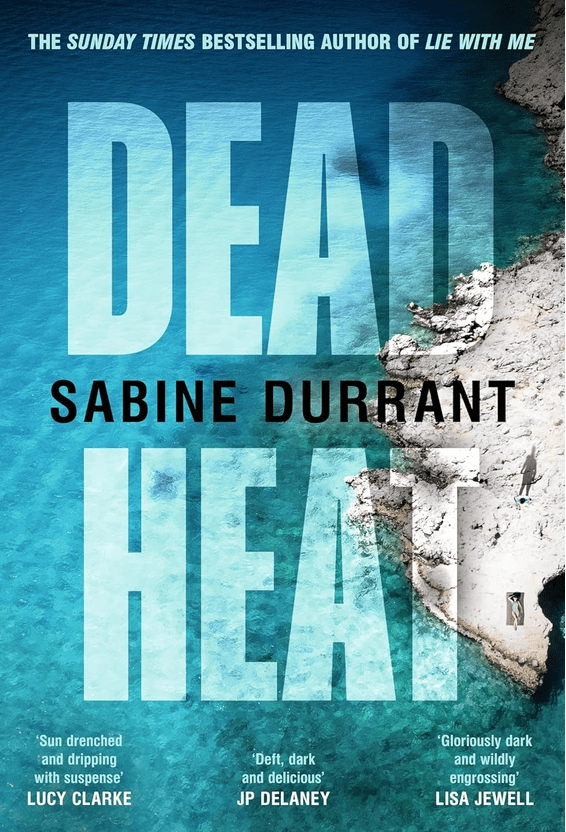

For Matt Grimshaw, everything has suddenly become rather ‘former’. Thanks to being sacked by his long-term employer, he is now a former journalist, and Takara is now his former lover, he having discovered her cavorting with a colleague in his London flat. Adam and Celia, a well-off media couple, are still his friends, however, and they have given him the key to the cottage next to their villa on the Mani Peninsula, part of the ancient kingdom of Sparta.

Matt spends a few days on his own there before Adam, Celia, their teenage daughter Lydia and her friend Jasmine arrive. Adam is disconcerted that across the bay a former abandoned folly, Arcadia, has been converted into a luxury compound by a tech billionaire called Reynash de Souza. The problem is that Adam and de Souza have, as they say, history. When de Souza throws a party for all the neighbourhood, what Dylan called ‘a simple twist of fate’ intervenes and turns the azure Aegean into something far, far darker.

In the background is a missing person, a man called Marc Ashley, a guest at de Souza’s Arcadia. One morning, he set out for a run and never came back. His sister Sarah is desperately trying to find him by a leafleting campaign and organising volunteer search parties.At the heart of the story is the relationship between Matt and Adam. Matt is a talented writer, but insecure and, perhaps, too sensitive to the needs of others. His emotional antennae are fine-wired, but to his own detrimental. Adam is, to use the old word, a cad. Charming, persuasive, charismatic even, he uses people. One such is a young woman called Amira, a former intern at Adam’s production company. He seduced her and is subsequently horrified when she turns up at de Souza’s mansion. She blackmails him, and Matt, ever loyal, agrees to be part of the deception involving a pay-off that will deceive Celia.

The book begins with one of those enigmatic prologues, date stamped well after the events of the main story. A man sits in a Greek court, watching a prisoner being sentenced. Sabine Durrant drops a fairly hefty hint that the observer is Matt Grimshaw, but who is the convicted man? Sabine Durrant not only deftly recreates the enervating physical climate, but makes us sweat in the oppressive emotional climate created by infidelity, old sins returning to haunt the perpetrator, and dangerous atmosphere caused by money mixed with power. Dead Heat is an immersive mystery beautifully woven with the threads of cruelty, revenge and deceit. It will be published by Century on 12th March.