Who was the most celebrated writer of ghost stories? The genre doesn’t lend itself particularly well to longer book form, and even classics like Henry James’s The Turn of The Screw and Susan Hill’s The Woman In Black are relatively slim volumes. The master of the shorter version and, in my view, a man who unrivalled in the art of chilling the spine, was MR James. Montague Rhodes James was born in Kent in 1862, and in his main professional life he became a renowned scholar, medievalist and academic, serving as Provost of King’s College Cambridge, and Provost of Eton. His first collection of ghost stories, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, was published in 1904 and has, as far as I am aware, never been out of print.

Who was the most celebrated writer of ghost stories? The genre doesn’t lend itself particularly well to longer book form, and even classics like Henry James’s The Turn of The Screw and Susan Hill’s The Woman In Black are relatively slim volumes. The master of the shorter version and, in my view, a man who unrivalled in the art of chilling the spine, was MR James. Montague Rhodes James was born in Kent in 1862, and in his main professional life he became a renowned scholar, medievalist and academic, serving as Provost of King’s College Cambridge, and Provost of Eton. His first collection of ghost stories, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, was published in 1904 and has, as far as I am aware, never been out of print.

From the age of three, until he was in his forties, James’s home was in Suffolk, and several of his most chilling tales were set in the county. Now, Simon Loxley, himself a Suffolk man who is a celebrated expert on typography, has written a book which examines James’s links with the county and the places which he is convinced that James had in his mind as the settings for such stories as Whistle and I’ll Come to You. Older readers of this review may remember a magnificent television adaptation of this story which was first shown in 1968, starring the great MIchael Hordern as the sceptical academic who, after rubbishing the very existence of a supernatural world, has a very nasty encounter with bed-sheets in his hotel room. A DVD is available (at a price), but as with so many other things, it’s on YouTube.

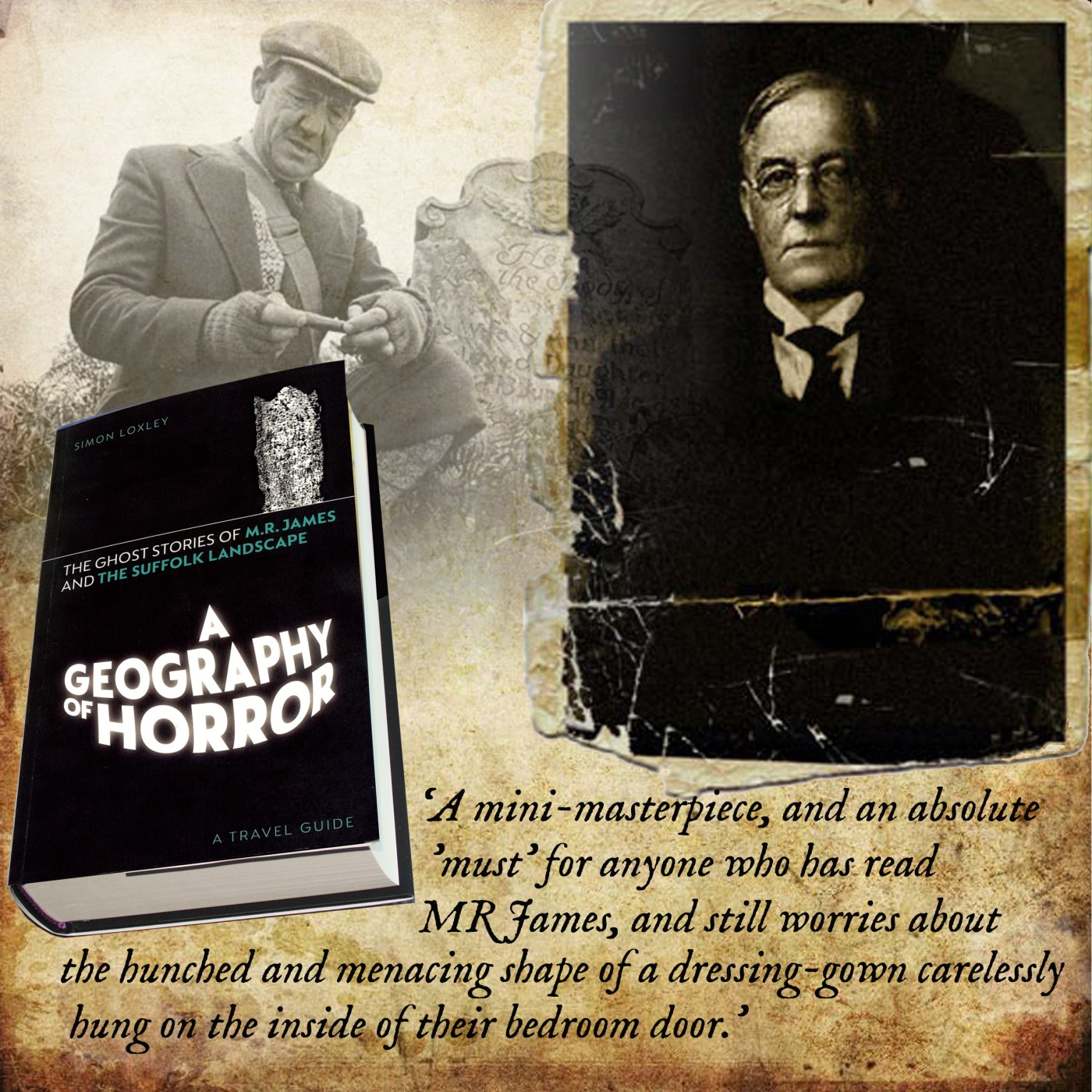

Simon Loxley’s book is, among other things, a superb piece of research. He has walked every inch of his territory, and has read every word that James wrote. He notes the distinctive Englishness of the characters and , in particular, their emotional restraint:

“They are people who would not normally foist their life story upon you at a moment’s notice. They have no-one close to confide in, so they carry the story with them, unspoken until, perhaps underv the encouragement of a social setting, they tell. That fits in with the perceived British national character of the period. The sanity and the solidarity of the characters is emphasised.”

Here, Loxley hits the button which reveals why the MR James stories are so believable. The people who experience the unpleasant, dusty, scuttling – and long since dead – entities that still terrify us today, are not gullible fools, nor are they emotionally fragile. Instead they are solid, pragmatic ‘tweedy types’ who live their lives based on evidence and things empirical.

The book is lavishly illustrated with maps and photographs, and the author examines James as a man, as a writer, and also looks at his contemporaries, predecessors in the genre, and those he influenced. Loxley is also a perceptive critic and does not shy away from identifying the stories which he believes are weaker than James at his very best. Anyone who lives in Suffolk, or plans a visit. will find particularly fascinating the examination of the eight stories that are precisely linked with locations within the county.

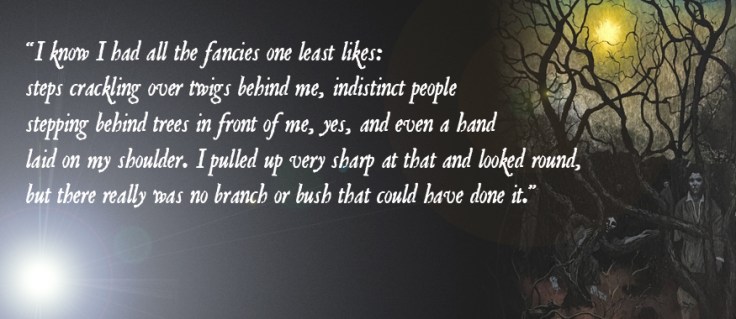

The first of these, The Ash Tree, remains embedded in the darkest corner of my imagination, and has been there ever since I first read the story in my teens. I am an incurable arachnaphobe and, despite having lived for several years in Australia, where daily acquaintance with the eight-legged devils was commonplace, the very though of hand-sized versions of the worst thing that God ever created leaping onto your face as you lie asleep still makes me sweat with terror. MR James may not have shared my visceral fear of these creatures. but he certainly knew that his words would strike terror into the minds of people who see spiders as the ultimate evil.

A Geography of Horror is a mini-masterpiece, and an absolute ‘must’ for anyone who has read MR James, and, like the unfortunate Professor Parkins. still worries about the hunched and menacing shape of a dressing-gown carelessly hung on the inside of their bedroom door. To buy a copy, the best thing is to go to Simon Loxley’s website, or contact him on sloxley@btinternet.com.

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure.

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure. The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.

The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.