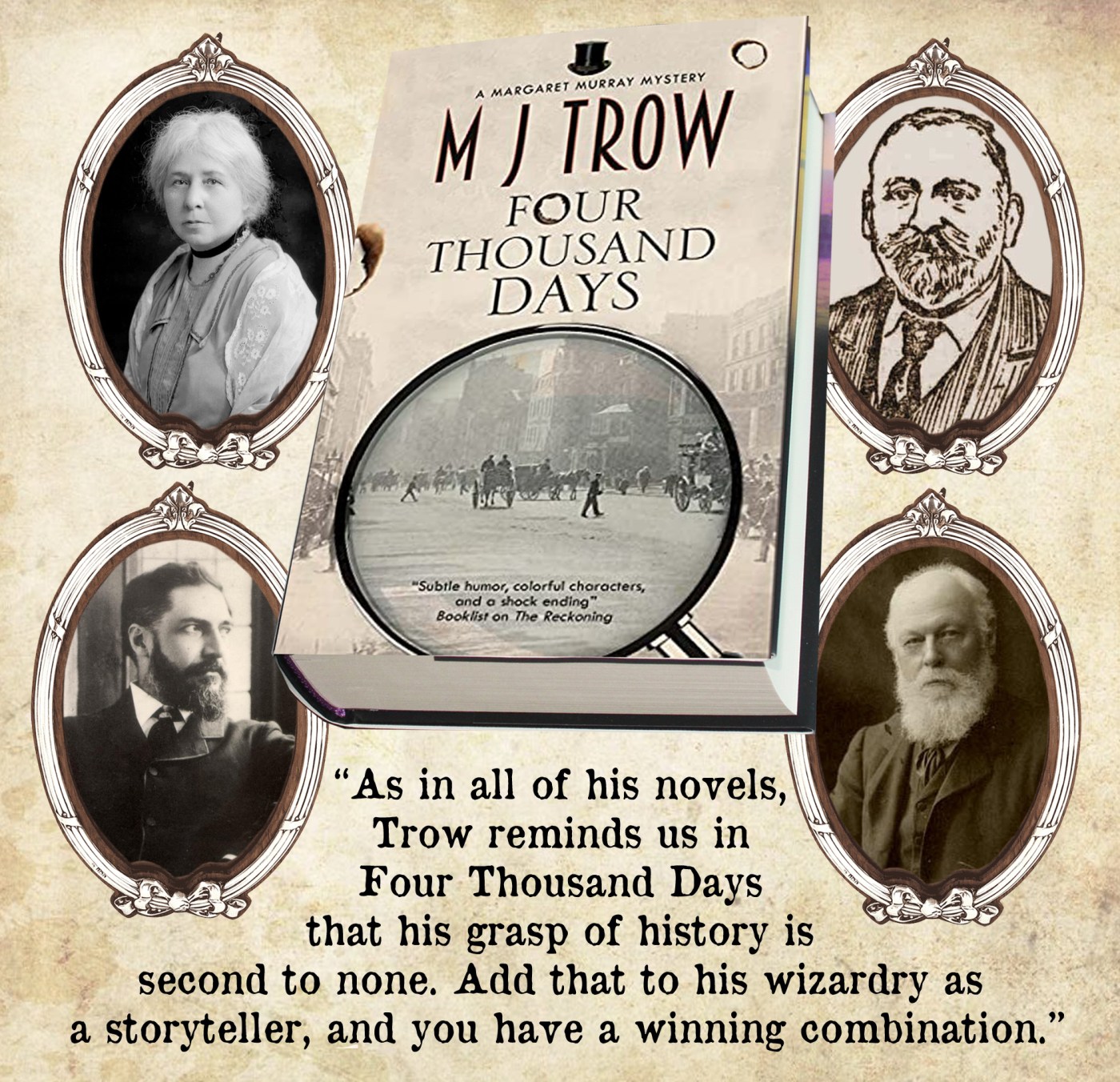

MJ Trow introduced us to the principle characters in this novel in the autumn of 2022 in Four Thousand Days (click to read the review) That was set in 1900, and had real-life archaeologist Margaret Murray solving a series of murders, helped by a young London copper, Constable Andrew Crawford. Now, it is May 1905, Andrew Crawford is now a Sergeant, has married into a rich family, and Margaret Murray is still lecturing at University College.

When a spiritualist medium is found dead at her dinner table, slumped face down in a bowl of mulligatawny soup, the police can find nothing to suggest criminality. It is only later, when a black feather appears, having been lodged in the woman’s throat, that Andrew Crawford suspects foul play. His boss, however is having none of it.

Two more mediums go to join the actual dead whose presence they ingeniously try to recreate for their clients, and the hunt is on for a serial killer. Crawford enlists the help of Margaret Murray, and under a pseudonym, she joins the spiritualist group to which the first murder victim has belonged. After an intervention by former Detective Inspector Edmund Reid who, amazingly, manages to convince people attending a seance that he is one of Europe’s most renowned spiritualists, we have a breathtaking finale in Margaret Murray’s dusty little office in University College.

Without giving too much away, I will tease you a little, and say that the killer is trying to find something, but isn’t sure who has it. There is a pleasing circularity here, by way of Jack the Ripper. Edmund Reid was one of the senior coppers who tried to bring the Whitechapel killer to justice, and MJ Trow has written one of the better studies of that case. One of the (many) theories about the motivation of JTR was that he was seeking revenge on the woman who gave him – or someone close to him – a fatal dose of syphilis, and he was simply working his way down a list.

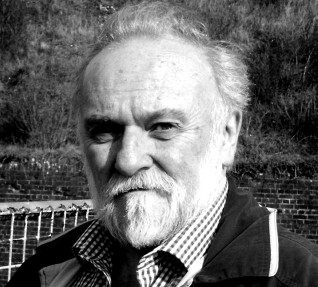

Trow was for many, many years a senior history teacher at a school on the Isle of Wight, and he appeared as his thinly disguised ‘self’ in the long running series of books featuring Peter ‘Mad Max’ Maxwell. I can’t think of another writer whose encyclopaedic knowledge of the past has been the steel backbone of his books. Don’t, however, make the mistake of thinking there is an overload of fact to the detriment of entertainment. Trow is a brilliantly gifted storyteller and, as far as I am concerned, Victorian and Edwardian London belong to him. Breaking The Circle is published by Severn House, and is out now. For our mutual entertainment, I have including a graphic which shows some of the real life individuals who appear in the story.

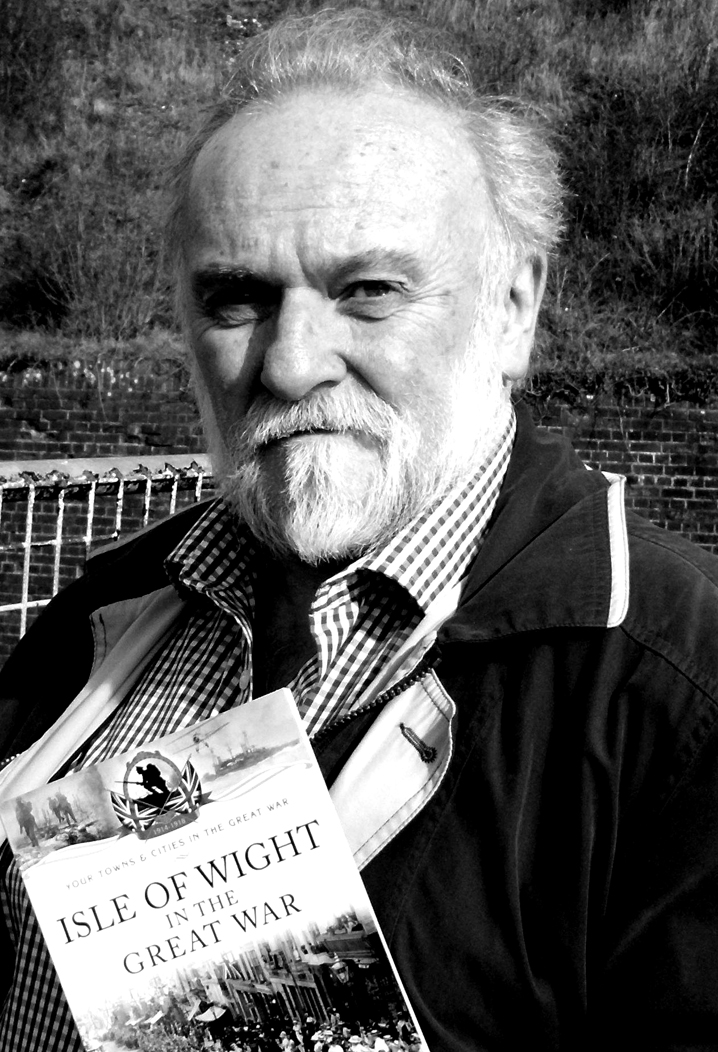

For more on MJ Trow and his books, click on the author image below.

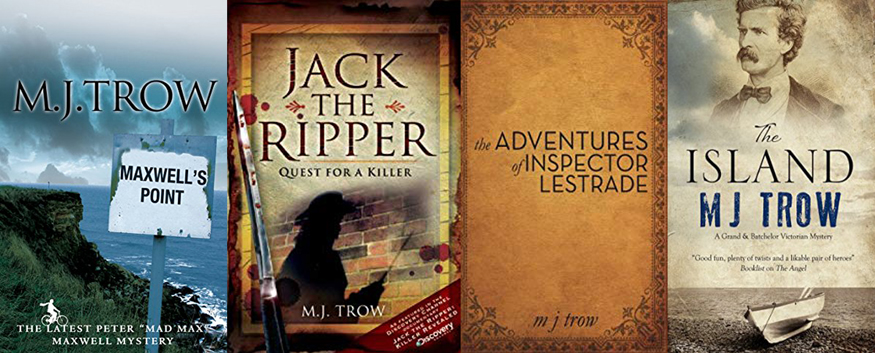

MJ is alive and well, and still writing, and Peter Maxwell appeared as recently as 2020 with Maxwell’s Summer. The series started in 1994 with Maxwell’s House, a title which (if you were around in the 1960s) will give you some idea of MJ’s wonderful sense of English domestic history – and his inability to resist a pun. The books are highly enjoyable, but never cosy. There is a streak of melancholy never far from the surface, and we are reminded that Maxwell’s first wife died when the car they were in was involved in a fatal collision. Max has never driven since, and his trusty bicycle is a regular prop in the stories. Max eventually marries his policewoman girlfriend Jackie Carpenter, which is only right and fair, since she is the plot device that has given him a very convenient ‘in’ with local murder investigations. MJ Trow has several other CriFi series to his name, and I list them below.

MJ is alive and well, and still writing, and Peter Maxwell appeared as recently as 2020 with Maxwell’s Summer. The series started in 1994 with Maxwell’s House, a title which (if you were around in the 1960s) will give you some idea of MJ’s wonderful sense of English domestic history – and his inability to resist a pun. The books are highly enjoyable, but never cosy. There is a streak of melancholy never far from the surface, and we are reminded that Maxwell’s first wife died when the car they were in was involved in a fatal collision. Max has never driven since, and his trusty bicycle is a regular prop in the stories. Max eventually marries his policewoman girlfriend Jackie Carpenter, which is only right and fair, since she is the plot device that has given him a very convenient ‘in’ with local murder investigations. MJ Trow has several other CriFi series to his name, and I list them below.

Inspector Lestrade – in which Trow ‘rehabilitates’ the much maligned copper in the Sherlock Holmes stories. 17 novels, beginning in 1985.

Inspector Lestrade – in which Trow ‘rehabilitates’ the much maligned copper in the Sherlock Holmes stories. 17 novels, beginning in 1985.

Grand & Batchelor are private investigators based in 1870s London and – much to the relief of James Batchelor, who is a terrible traveller – Last Nocturne has its feet securely on home soil. Grand is from a wealthy New England family, and fought bravely for the Union in The War Between The States, while Batchelor is a journalist by trade. Murder – what else? – is the name of the game in this book, and the victims are, you might say ‘on the game’. Cremorne Gardens were popular pleasure gardens beside the River Thames in Chelsea, but after dark, the ‘pleasure’ sought by its denizens was not of the innocent kind. ‘Ladies of the Night’ are being murdered – poisoned with arsenic – but the killer doesn’t interfere with them, as the saying goes, but instead leaves books by their dead bodies.

Grand & Batchelor are private investigators based in 1870s London and – much to the relief of James Batchelor, who is a terrible traveller – Last Nocturne has its feet securely on home soil. Grand is from a wealthy New England family, and fought bravely for the Union in The War Between The States, while Batchelor is a journalist by trade. Murder – what else? – is the name of the game in this book, and the victims are, you might say ‘on the game’. Cremorne Gardens were popular pleasure gardens beside the River Thames in Chelsea, but after dark, the ‘pleasure’ sought by its denizens was not of the innocent kind. ‘Ladies of the Night’ are being murdered – poisoned with arsenic – but the killer doesn’t interfere with them, as the saying goes, but instead leaves books by their dead bodies.

e may not have been the first to do so, but George MacDonald Fraser entertained many of us with the idea of writing novels where we get to meet actual key players from history. His archetypal bounder Harry Flashman, himself nicked from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, rubbed shoulders and crossed swords with a variety of celebrities, including Otto von Bismarck, Abraham Lincoln, and Emperor Franz Joseph. The late Philip Kerr narrowed things down as he introduced us to Heinrich Himmler, Reinhardt Heydrich and Joseph Goebbels in his Bernie Gunther novels.

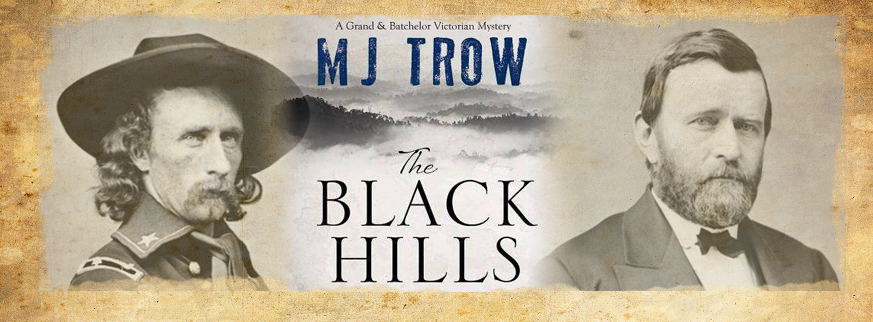

e may not have been the first to do so, but George MacDonald Fraser entertained many of us with the idea of writing novels where we get to meet actual key players from history. His archetypal bounder Harry Flashman, himself nicked from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, rubbed shoulders and crossed swords with a variety of celebrities, including Otto von Bismarck, Abraham Lincoln, and Emperor Franz Joseph. The late Philip Kerr narrowed things down as he introduced us to Heinrich Himmler, Reinhardt Heydrich and Joseph Goebbels in his Bernie Gunther novels. One of the enjoyable conceits of the series is the comparison of how the two men behave when out of their cultural comfort zone. Grand is no gnarled backwoodsman, as his parents are wealthy New Hampshire patricians, but there is generally more fun to be had when Batchelor is trying to navigate the social niceties – or lack of them – in America. Trow, like MacDonald Fraser and Kerr, is a shameless name-dropper and we are not many pages into The Black Hills before we have bumped into George Armstrong Custer and broken into The White House to have a conversation with its current occupant, Ulysses Simpson Grant.

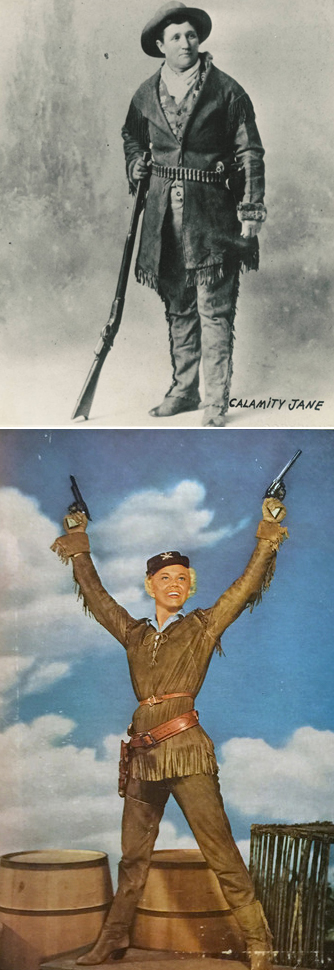

One of the enjoyable conceits of the series is the comparison of how the two men behave when out of their cultural comfort zone. Grand is no gnarled backwoodsman, as his parents are wealthy New Hampshire patricians, but there is generally more fun to be had when Batchelor is trying to navigate the social niceties – or lack of them – in America. Trow, like MacDonald Fraser and Kerr, is a shameless name-dropper and we are not many pages into The Black Hills before we have bumped into George Armstrong Custer and broken into The White House to have a conversation with its current occupant, Ulysses Simpson Grant. I readily put my hand up. When I read the words The Black Hills, the first image that flashed before my eyes was that of Doris Day in her buckskins and with her blonde bob under a troopers’ hat. Yes, my age is showing, but the 1953 film Calamity Jane starring Doris Day in the title role featured great songs like The Deadwood Stage, Secret Love and The Black Hills of Dakota. Trow is pretty much of my generation. He was a couple of years behind me at a minor public school (but don’t hold that against either of us). Never one to miss a trick, he features Calamity Jane in The Black Hills but, my oh my, Doris Day she ain’t. Short, pug-ugly and a stranger to personal hygiene, Jane Cannery is a fixture at Fort Abraham Lincoln. She is rarely sober and earns her living by washing the long johns of the Seventh Cavalry men who guard the frontier. She is notoriously quick on the draw with her Navy Colt, and the soldiers take care to give her a wide berth when she is in one of her moods.

I readily put my hand up. When I read the words The Black Hills, the first image that flashed before my eyes was that of Doris Day in her buckskins and with her blonde bob under a troopers’ hat. Yes, my age is showing, but the 1953 film Calamity Jane starring Doris Day in the title role featured great songs like The Deadwood Stage, Secret Love and The Black Hills of Dakota. Trow is pretty much of my generation. He was a couple of years behind me at a minor public school (but don’t hold that against either of us). Never one to miss a trick, he features Calamity Jane in The Black Hills but, my oh my, Doris Day she ain’t. Short, pug-ugly and a stranger to personal hygiene, Jane Cannery is a fixture at Fort Abraham Lincoln. She is rarely sober and earns her living by washing the long johns of the Seventh Cavalry men who guard the frontier. She is notoriously quick on the draw with her Navy Colt, and the soldiers take care to give her a wide berth when she is in one of her moods.

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery:

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery: MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

The Island is the latest episode in the eventful partnership between two gentleman detectives in Victorian London. James Batchelor is a former journalist, a ‘gentleman’ in manners and intelligence, if not by upbringing, while his colleague Matthew Grand is an American former soldier, and scion of a very wealthy patrician New Hampshire family. We first met them in

The Island is the latest episode in the eventful partnership between two gentleman detectives in Victorian London. James Batchelor is a former journalist, a ‘gentleman’ in manners and intelligence, if not by upbringing, while his colleague Matthew Grand is an American former soldier, and scion of a very wealthy patrician New Hampshire family. We first met them in  A few words in praise of the author. Meiron Trow (right) is one of the most erudite and entertaining writers in the land. Over thirty years ago he began his tongue in cheek series rehabilitating the much-put-upon Inspector Lestrade, and I loved every word. I then became hooked on his Maxwell series, featuring a very astute crime-solving history teacher who, while eschewing most things modern, manages to be hugely respected by the sixth-formers (Year 12 and 13 students in new money) in his charge, while managing to terrify and alarm the younger ‘teaching professionals’ who run his school. I was well into the Maxwell series before I realised that MJ Trow and I had two things (at least) in common. Firstly, he went to the same school as I did, although I have to confess he was a couple of years ‘below’ me and would have been dismissed at the time as a pesky ‘newbug’. Secondly, and much more relevant to my love of his Maxwell books, I discovered that we were both senior teachers in state secondary schools, and shared a disgust and contempt for the tick-box mentality characterising the so-called ‘leadership’ of high schools.

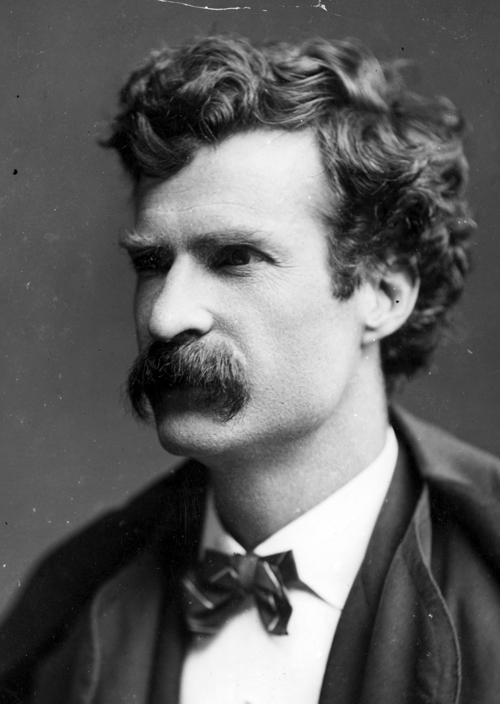

A few words in praise of the author. Meiron Trow (right) is one of the most erudite and entertaining writers in the land. Over thirty years ago he began his tongue in cheek series rehabilitating the much-put-upon Inspector Lestrade, and I loved every word. I then became hooked on his Maxwell series, featuring a very astute crime-solving history teacher who, while eschewing most things modern, manages to be hugely respected by the sixth-formers (Year 12 and 13 students in new money) in his charge, while managing to terrify and alarm the younger ‘teaching professionals’ who run his school. I was well into the Maxwell series before I realised that MJ Trow and I had two things (at least) in common. Firstly, he went to the same school as I did, although I have to confess he was a couple of years ‘below’ me and would have been dismissed at the time as a pesky ‘newbug’. Secondly, and much more relevant to my love of his Maxwell books, I discovered that we were both senior teachers in state secondary schools, and shared a disgust and contempt for the tick-box mentality characterising the so-called ‘leadership’ of high schools. I digress, so back to New Hampshire in the early spring of 1873. The guests begin to arrive, and the ‘downstairs’ staff under the stern eye of the enigmatic butler, Waldo Hart, are emulating the proverbial blue-arsed fly. Trow, at this point, gleefully takes the template of the traditional country house mystery, and has his evil way with it. Despite the title of the book, we are not quite in Soldier Island (And Then There Were None) territory, but Rye is far enough from Boston to make sure that when the first murder happens, the real policemen are too far away and too engrossed with their city crime to pay much attention, even when when of the possible suspects is a certain Mr Samuel Langhorne Clemens. (left)

I digress, so back to New Hampshire in the early spring of 1873. The guests begin to arrive, and the ‘downstairs’ staff under the stern eye of the enigmatic butler, Waldo Hart, are emulating the proverbial blue-arsed fly. Trow, at this point, gleefully takes the template of the traditional country house mystery, and has his evil way with it. Despite the title of the book, we are not quite in Soldier Island (And Then There Were None) territory, but Rye is far enough from Boston to make sure that when the first murder happens, the real policemen are too far away and too engrossed with their city crime to pay much attention, even when when of the possible suspects is a certain Mr Samuel Langhorne Clemens. (left)