Fergus Hume’s 1886 novel is rightly regarded as one of the building blocks of crime fiction.To put it into some kind of chronological context. Emile Gaboriau published Monsieur Lecoq in 1867, The Moonstone appeared in 1868, while A Study In Scarlet came out in 1887.

The story begins simply enough. It is the small hours of the morning in 1880s Melbourne. A cab driver sees two men, dressed in evening clothes. One appears to be very drunk. The sober man puts his drunken companion into the cab and walks away. The drunk is trying to explain to the cabbie that he needs to go to St Kilda, a suburb near the sea. Just then the sober man returns, and tells the driver to take them to St Kilda. About half way there, the sober man tells the cabbie to stop. He says that he will walk back into the city, but that his drunken friend will let the driver know where to drop him off. The cabbie continues for a while but, hearing nothing from the passenger, stops to check. The man is dead, a handkerchief soaked in chloroform across his face. The cabbie turns around and heads for the city police station.

Mr Gorby, the police detective investigating the crime, soon has the case cracked. The dead man is Oliver Whyte. His companion in the cab was, apparently, Brian Fitzgerald. The men were rivals in love, the lady in question being Madge Frettlby, the daughter of a rich businessman. Fitzgerald appears to be the only possible suspect, and he is arrested.

Awaiting trial, Fitzgerald frustrates his expensive lawyer by stating yes, he did meet Whyte and put him in the cab, then walked away but, crucially, did not return. We then have perhaps the earliest use of what has become a tried and trusted crime fiction trope – that of the suspect who has a genuine alibi, but dare not reveal it because of the dishonour it would bring down on someone else. Perhaps we could call this The Gentleman’s Dilemma.

Fitzgerald claims that a woman delivered a written message to him at his club, after he had left Whyte with the cabbie. The message implored him to visit a dying woman in a gin den in an alley off Little Bourke Street. The messenger was one Sal Rawlins who has since disappeared, being last heard of traveling to Sydney with a Chinaman. After a hefty reward is offered Sal is found and testifies, thus establishing Fitzgerald’s alibi. But who was the dying woman, and why did she need to use her final moments to talk to Fitzgerald? Hume’s solution is both neat and daring.

The book is certainly ‘of its time’ in some ways. One of the conventions of the day was that words spoken by ‘the menials’ – working class or peasant characters – were heavily phoneticised, so that no missing final ‘g’ in words ending in ‘ing’ or any missing ‘h’ at the beginning of ‘he’, ‘has’ or ‘home’ goes unpunished.

Imagined as a screenplay, TMOAHC is magnificently melodramatic, with enough betrayal, dark secrets, swooning, hands clasped to fevered brows and tarnished virtue to set Victorian (in both senses of the word) pulses racing. It is cleverly done, however, and the true identity of the killer is only revealed in the last few pages. Hume, towards the end, devotes several pages to the theme that we mortals are little more than chess pieces being moved about the board for their own amusement by the ‘Immortals’ of Greek myth. Just five years later, in 1891, Thomas Hardy was to end Tess of the d’Urbervilles with the same bitter thoughts.

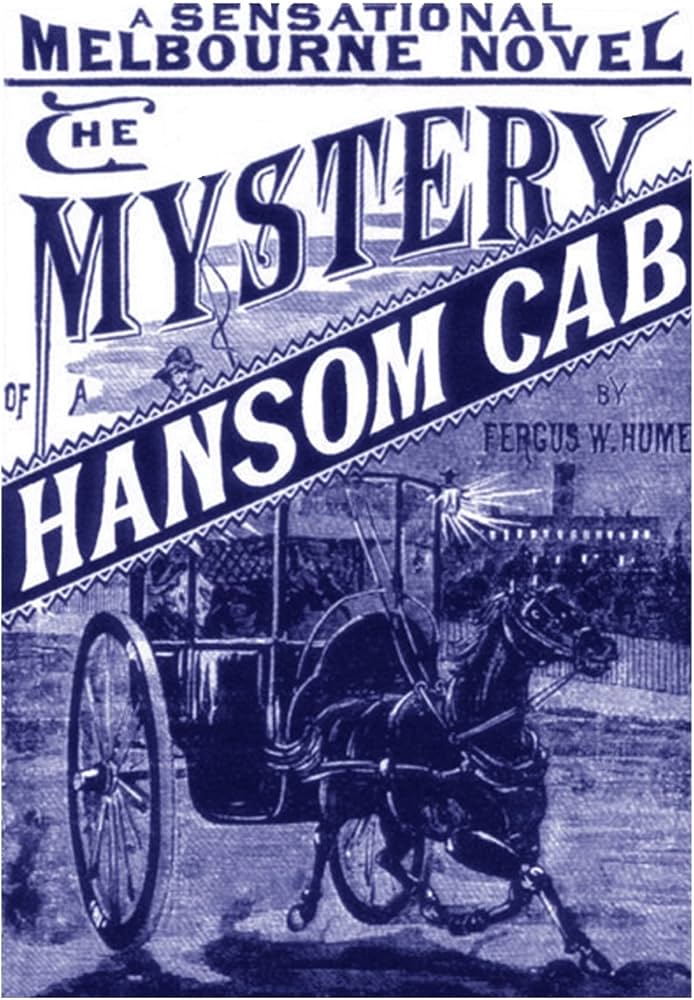

Hume was forced to self – publish the first edition of this novel, but sales gathered pace thereafter, and it has been endlessly reprinted. In his preface to this edition Hume reveals that prior to publication he made several changes, including the identity of the killer. He also tells us that he sold the rights to the novel to a group of speculators, no doubt for a tidy sum, but in doing so cut himself off from later profits. He regarded himself as, first and foremost, a New Zealander. His parents moved from England to New Zealand when he was very young, and it was there that he was educated and graduated as a barrister. He then moved to Australia for a few years, but eventually returned to England, where he died in 1932 at the age of 73. If you click the image below, it will take you to Project Gutenberg where you can download a free digital copy.