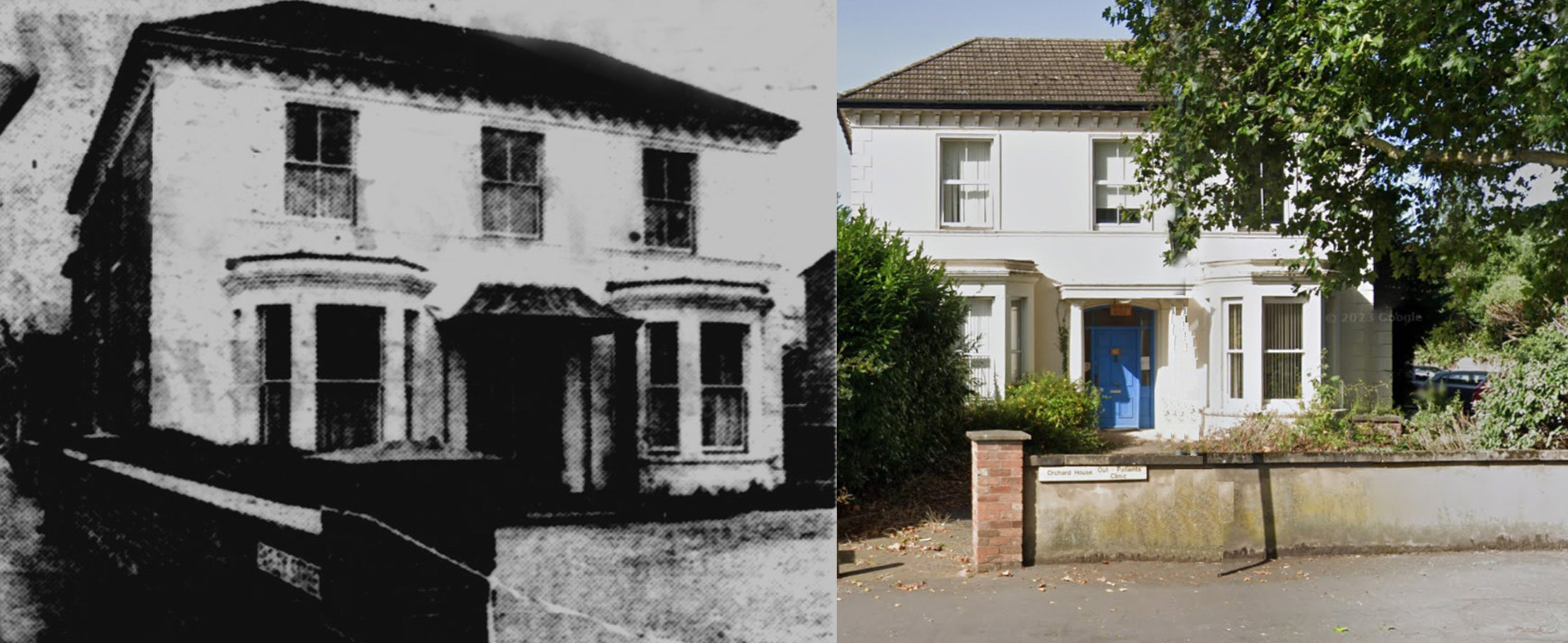

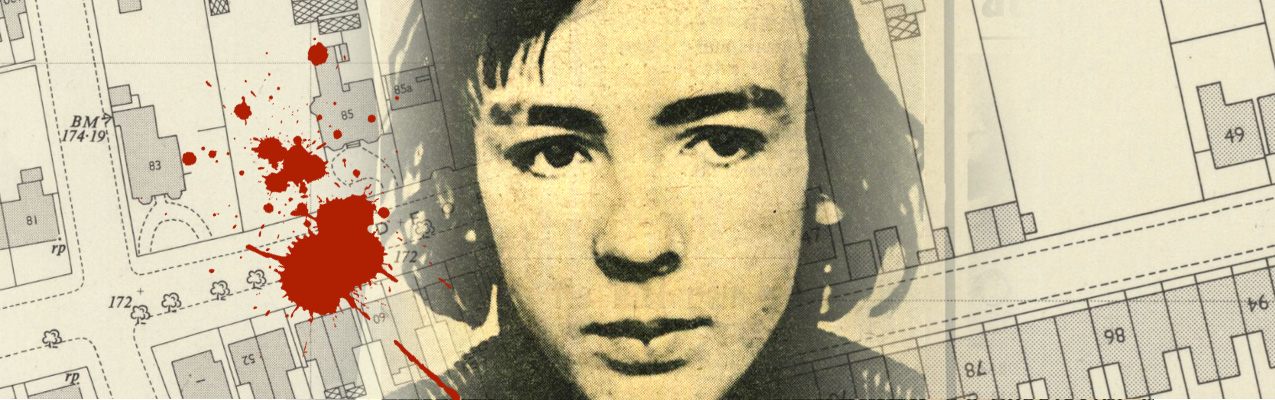

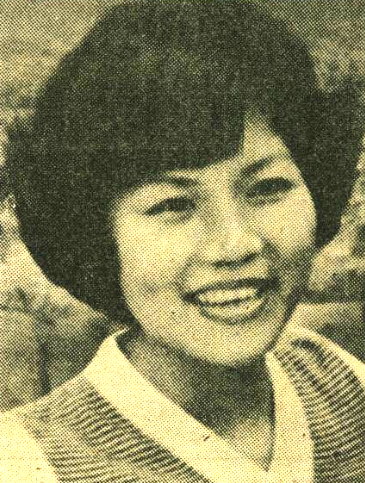

SO FAR: In the early hours of Monday 2nd February 1976, the butchered body of Chinese nurse Tze Yung Tong (left) was found in her room in a nurses’ hostel at 83 Redford Road, Leamington Spa. Other young women had heard noises in the night, but had been too terrified to venture beyond their locked doors. We can talk about ships passing in the night, in the sense of two people meeting once, but never again. Tze Yung Tong was to meet her killer just the one fatal time.

SO FAR: In the early hours of Monday 2nd February 1976, the butchered body of Chinese nurse Tze Yung Tong (left) was found in her room in a nurses’ hostel at 83 Redford Road, Leamington Spa. Other young women had heard noises in the night, but had been too terrified to venture beyond their locked doors. We can talk about ships passing in the night, in the sense of two people meeting once, but never again. Tze Yung Tong was to meet her killer just the one fatal time.

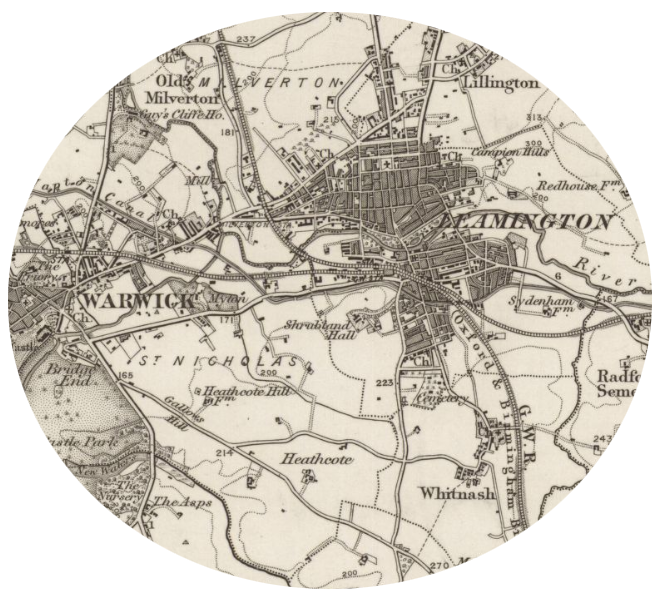

Gerald Michael Reilly was born in Birmingham in 1957, but he and his family moved to Leamington. After primary school, he went to Dormer School, which then had its main building on Myton Road. He was described as quiet and pleasant, but not one of life’s high achievers. In 1974 he had a brief spell in the Merchant Navy before returning to Leamington to live with his parents at 49 Plymouth Place and work as a builders’ labourer. He was engaged to be married to Julie, a young woman from the north of England he had met during his Merchant Navy days.

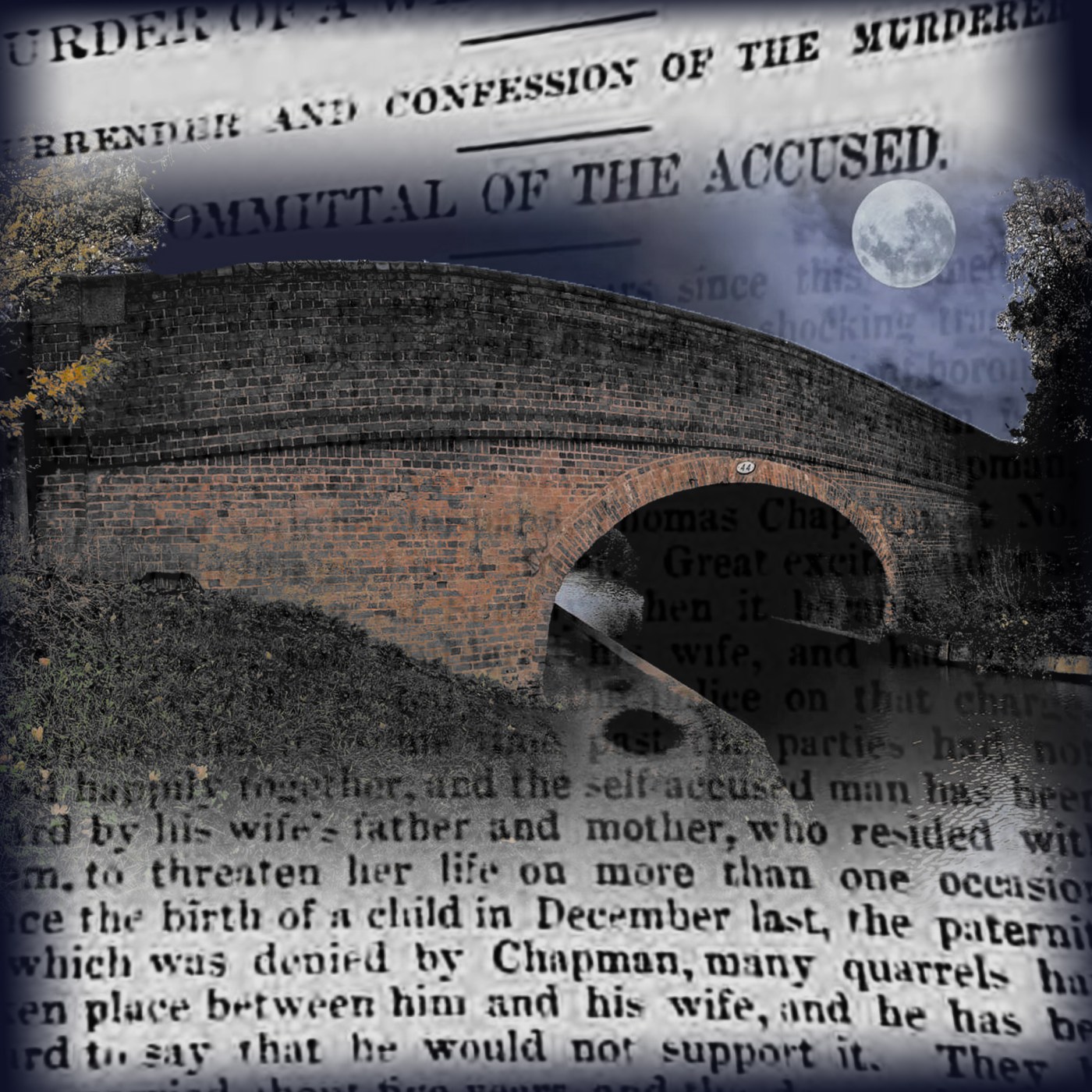

On the evening of 1st February 1976, he was observing the moral code of the time by sleeping downstairs, while Julie was chastely abed upstairs. At some point, he decided he needed sex. It was never going to happen at home, so he let himself out of the house, and walked the 200 yards or so along snow-covered pavements to the nurses’ hostel on Redford Road. There, he shinned up a drain-pipe, and padded along the corridors hoping for an unlocked door. He found one. It was Tze Yung Tong’s room.

This is where the story goes into “you couldn’t make it up” territory. It was estimated that Reilly spent 90 minutes going about his dreadful work on the young nurse. Then, still clutching the sheath knife with which he had disembowelled Tze Yung Tong, he retraced his steps to Plymouth Place and went back to sleep.Just twelve days later, with hundreds of police banging their heads against a brick wall, Gerald and Julie were married with all the traditional trappings at St Peter’s church on Dormer Place. In those days honeymoons were rather prosaic by modern standards, so the star-crossed lovers set off for the West Country. Julie had her “going away” outfit, but Gerald brought with him something more significant – the knife with which he gutted Tze Yung Tong. In a bizarre attempt at concealment, he hid the blade in a toilet cistern at a Bath hotel.

Below, Gerald and Julie on their wedding day

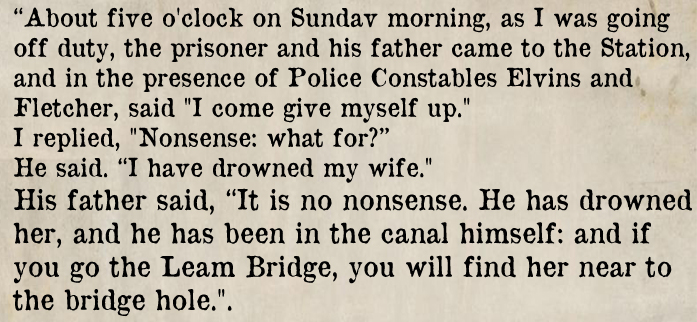

By this time, whatever passed for logical thought in Reilly’s mind had gone AWOL. Upon returning to Leamington, and hearing about the intense fingerprinting initiative, he decided that the game was up and, with his uncle for company, turned himself in. The irony is that the police, in desperation, had announced that there was one set of prints they had not been able to eliminate. Assuming they were his, Reilly offered his wrists for the handcuffs. The prints were not his.

Despite his palpable guilt, Reilly was endlessly remanded, made numerous appearances before local magistrates, but eventually had brief moment in a higher court. At Birmingham Crown Court in December, Mr Justice Donaldson (right) found him guilty of murder, and sentenced him to life, with a minimum tariff of 20 years.In 1997, a regional newspaper did a retrospective feature on the case. By then, the police admitted that he had already been released. Do the sums. Reilly, the Baby-Faced Butcher may still be out there. He will only be in his late 60s. Ten years younger than me. One of the stranger aspects of this story is that, as far as I can tell, at no time did solicitors and barristers working to defend Reilly ever suggest that his actions were that of someone not in his right mind. By contrast, in an earlier shocking Leamington case in 1949, The Sten Gun Killer (click the link to read it) the ‘insanity card’ was played with great success. Perhaps must face the fact that sometimes, sheer evil can exist in human beings who are perfectly sane and rational.

Despite his palpable guilt, Reilly was endlessly remanded, made numerous appearances before local magistrates, but eventually had brief moment in a higher court. At Birmingham Crown Court in December, Mr Justice Donaldson (right) found him guilty of murder, and sentenced him to life, with a minimum tariff of 20 years.In 1997, a regional newspaper did a retrospective feature on the case. By then, the police admitted that he had already been released. Do the sums. Reilly, the Baby-Faced Butcher may still be out there. He will only be in his late 60s. Ten years younger than me. One of the stranger aspects of this story is that, as far as I can tell, at no time did solicitors and barristers working to defend Reilly ever suggest that his actions were that of someone not in his right mind. By contrast, in an earlier shocking Leamington case in 1949, The Sten Gun Killer (click the link to read it) the ‘insanity card’ was played with great success. Perhaps must face the fact that sometimes, sheer evil can exist in human beings who are perfectly sane and rational.

FOR OTHER LEAMINGTON & WARWICK MURDER CASES

CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW