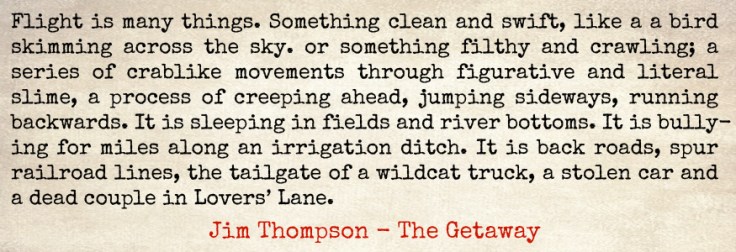

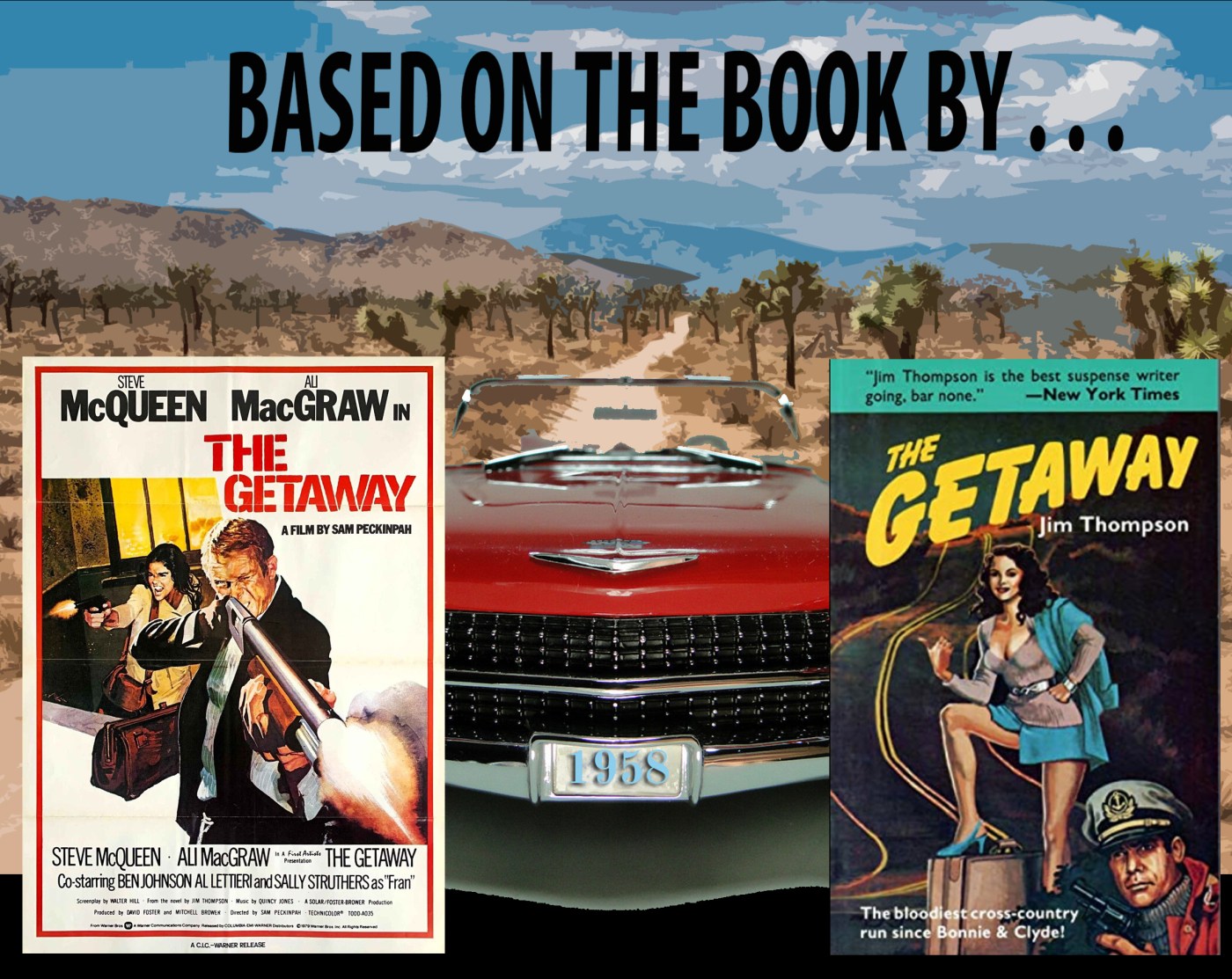

Jim Thompson’s thriller was published in 1958, and it was first filmed in 1972. The story centres on a career criminal Carter ‘Doc’ McCoy, his wife Carol and a psychotic accomplice called Rudy Torrento. They execute a bank heist in Beacon City, getting away with a cool quarter of a million dollars. Each man plans on killing the other afterwards but McCoy strikes first, leaving Torrento for dead in a dried up stream bed. As the McCoys take to the highway news of the Beacon City heist (and the corpses left as collateral damage) is all over the airwaves. The fugitives’ next port of call is the isolated home of a man named Beynon, the boss of the State Parole Board. For a large bribe delivered by Carol McCoy, it was Beynon who got McCoy out of the penitentiary well ahead of the time he was serving for his previous conviction.

McCoy still owes Beynon the largest part of the bribe, and as the two men talk, the drunken official implies that there had been more than just a financial transaction between himself and Carol while McCoy had been locked up. Carol, who had been waiting outside in the car, comes into the room and shoots Beynon dead. Then the McCoys abandon the highway in Kansas City and decide to head by rail to Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, the story is about to get even more bloody. McCoy’s bullet had not killed Torrento, but been deflected by the buckle on his shoulder holster. Still badly wounded, Torrento gets himself patched up by veterinarian Harold Clinton, but then takes the vet and his wife hostage as he vows to find the McCoys and take his revenge. As they hop from one cheap motel to another Torrento beds Fran and forces Harold to watch:

‘Mrs Clinton smirked lewdly. Rudy winked at her husband.

“It’s okay with you, ain’t it, Clint? You’ve got no objections?”

“ Why, no. No, of course not”, Clinton said hastily, “It’s, very sensible.”

And he winced as his wife laughed openly. He did not know how to object. In his inherent delicacy and decency, he could not admit that there was anything to object to. He heard them that night-and subsequent nights of the leisurely journey westwards. But he kept his back turned and his eyes closed, feeling no shame or anger but only an increasing sickness of soul.’

In keeping with the ongoing carnage, Harold Clinton – soul first sickened, and then dead, commits suicide, while Doc manages to keep ahead of the game – just – by gunning down Rudy and Mrs Clinton.

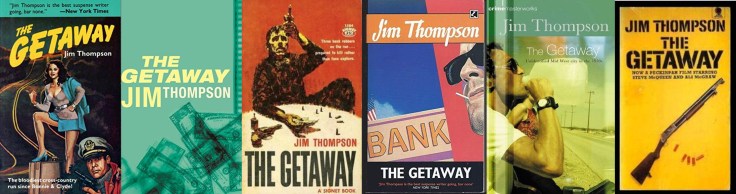

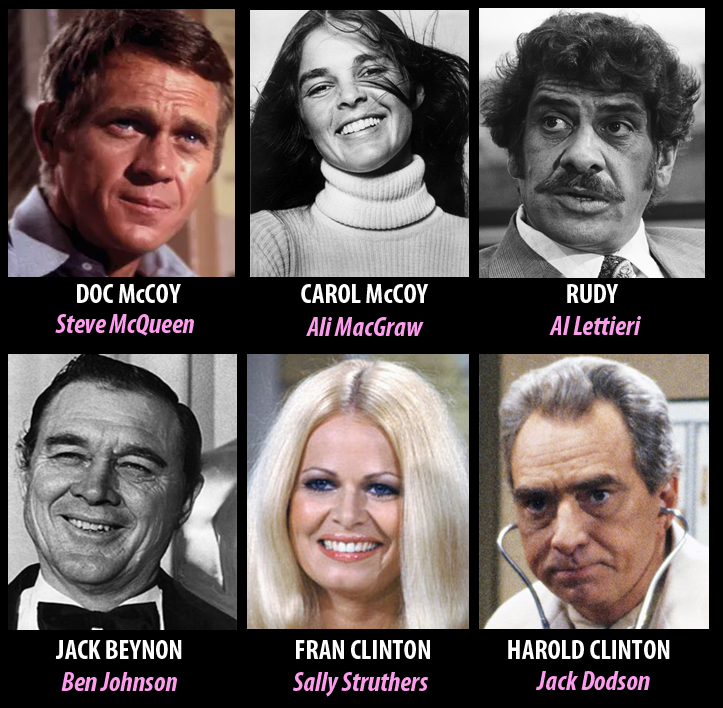

The 1972 film, (trailer above) directed by Sam Peckinpah with a screenplay (eventually) by Walter Hill was ‘wrong’ from the word go, at least in terms of the book. It is hardly surprising that Jim Thompson (right) hired to write the screenplay, didn’t last long on the project and was sacked. Star man was Hollywood golden boy Steve McQueen. With box office hits like The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963) Bullitt (1968) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) on his resumé, he wasn’t ever going to be right for the homicidal and totally amoral Doc McCoy. The producers were probably of the mindset that they had the star, so to hell with the book. The film Doc McCoy is a criminal for sure, but he doesn’t murder people. He’s a Robin Hood or a (film version) Clyde Barrow. Beynon is the villain of the piece, and Rudy is working for him. This was the cast:

The 1972 film, (trailer above) directed by Sam Peckinpah with a screenplay (eventually) by Walter Hill was ‘wrong’ from the word go, at least in terms of the book. It is hardly surprising that Jim Thompson (right) hired to write the screenplay, didn’t last long on the project and was sacked. Star man was Hollywood golden boy Steve McQueen. With box office hits like The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963) Bullitt (1968) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) on his resumé, he wasn’t ever going to be right for the homicidal and totally amoral Doc McCoy. The producers were probably of the mindset that they had the star, so to hell with the book. The film Doc McCoy is a criminal for sure, but he doesn’t murder people. He’s a Robin Hood or a (film version) Clyde Barrow. Beynon is the villain of the piece, and Rudy is working for him. This was the cast:

I’d better mention the 1994 version of the story. Starring Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger in the lead roles, it took even more liberties with the original story, in spite of (or perhaps because of) Walter Hill being on screenwriting duties. Wkipedia states, succinctly:

“The film flopped at the box office, but it enjoyed lucrative success in the home video market.”

As a critic once wrote of a record that flopped:

“It wasn’t released – it escaped.”

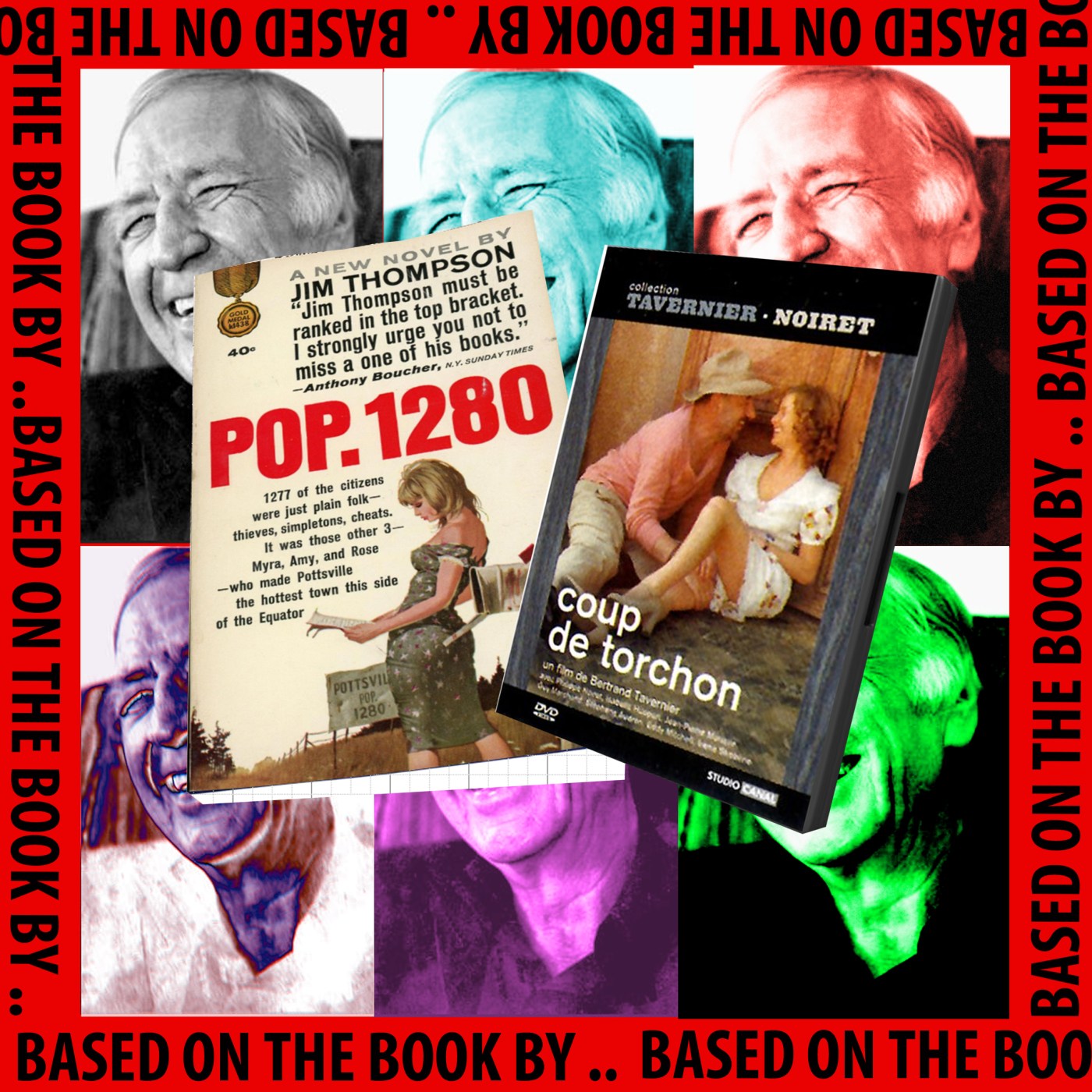

Back to the comparison between the Steve McQueen version of Doc McCoy and the original. Like the dreadful lawmen in two other Thompson classics (click the links for more information) The Killer Inside Me and Pop.1280, McCoy has a public persona:

“He was Doc McCoy, and Doc McCoy was born to the obligation of being one hell of a guy. Persuasive, impelling of personality; insidiously likable and good-humoured and imperturbable one of the nicest guys you’d ever meet, that was Doc McCoy.”

We soon learn, however, in the novel, that McCoy is a ruthless and stone cold killer. Rudy Tarrento is a monster, but he has something of an excuse. He is insane. Doc, though, is – by all interpretations – perfectly rational and in good mental health. In the film, after much ammunition is expended in various shoot-outs, Doc and Carol buy an old truck from a cowboy (played by the legendary Slim Pickens – left) and – almost literally – drive off into the Mexican sunset, full of life and love, with most of the loot intact. The ending of the novel is – to put it mildly – enigmatic. It has the feel of an hallucination. According to Steven King:

We soon learn, however, in the novel, that McCoy is a ruthless and stone cold killer. Rudy Tarrento is a monster, but he has something of an excuse. He is insane. Doc, though, is – by all interpretations – perfectly rational and in good mental health. In the film, after much ammunition is expended in various shoot-outs, Doc and Carol buy an old truck from a cowboy (played by the legendary Slim Pickens – left) and – almost literally – drive off into the Mexican sunset, full of life and love, with most of the loot intact. The ending of the novel is – to put it mildly – enigmatic. It has the feel of an hallucination. According to Steven King:

“If you have seen only the film version of The Getaway, you have no idea of the existential horrors awaiting Doc and Carol McCoy at the point where Sam Peckinpah ended the story.”

Doc and Carol, after avoiding the land border into Mexico via a fishing boat, end up in a mountain enclave ruled by a man known as El Rey. The last few pages read like something from a surreal nightmare, a kind of Twin Peaks world where nothing makes sense. Our less-than-starstruck lovers meet Dr. Vonderschied, a friend of the late Rudy. Each has asked the doctor to perform surgery on the other, and make sure that the medical intervention proves fatal. The doctor refuses both requests, and the book ends with Doc and Carol clinking glasses to celebrate their ‘successful getaway.”

Thompson’s first major success came in 1952 with The Killer Inside Me and it remains grimly innovative. Psychopathic killers have become pretty much mainstream in contemporary crime fiction, but there can be few who chill the blood in quite the same way as Thompson’s West Texas Deputy Sheriff Lou Ford. His menace is all the more compelling because he is the narrator of the novel, and a few hundred words in we are left in no doubt that the dull but amiable law officer, who bores local people stupid with his homespun cod-philosophical clichés, is actually a creature from the darkest reaches of hell.

Thompson’s first major success came in 1952 with The Killer Inside Me and it remains grimly innovative. Psychopathic killers have become pretty much mainstream in contemporary crime fiction, but there can be few who chill the blood in quite the same way as Thompson’s West Texas Deputy Sheriff Lou Ford. His menace is all the more compelling because he is the narrator of the novel, and a few hundred words in we are left in no doubt that the dull but amiable law officer, who bores local people stupid with his homespun cod-philosophical clichés, is actually a creature from the darkest reaches of hell. Joyce is savvy, and world-weary, but when Ford’s “pardon me, Ma’am,” charm strikes the wrong note, she slaps him. He slaps her back and the encounter takes a dark turn when Ford takes off his belt and gives Joyce what used to be known as “a leathering.” She responds to the beating with obvious arousal, and the pair begin a violent sado-sexual affair.

Joyce is savvy, and world-weary, but when Ford’s “pardon me, Ma’am,” charm strikes the wrong note, she slaps him. He slaps her back and the encounter takes a dark turn when Ford takes off his belt and gives Joyce what used to be known as “a leathering.” She responds to the beating with obvious arousal, and the pair begin a violent sado-sexual affair. A key figure in Ford’s life is Amy, his long-time girlfriend. Thompson paints her as physically attractive, but socially constrained. She is a primary school teacher from a good local family who, despite responding to Ford’s violent sexual ways, is determined to marry him. As the dark clouds of suspicion begin to shut the daylight out of Lou Ford’s life, she is the next to die, and Ford’s clumsy attempt to frame someone else for her death is the tipping point. Thereafter his downfall is rapid, and his final moments are as brutal and savage as anything he has inflicted on other people.

A key figure in Ford’s life is Amy, his long-time girlfriend. Thompson paints her as physically attractive, but socially constrained. She is a primary school teacher from a good local family who, despite responding to Ford’s violent sexual ways, is determined to marry him. As the dark clouds of suspicion begin to shut the daylight out of Lou Ford’s life, she is the next to die, and Ford’s clumsy attempt to frame someone else for her death is the tipping point. Thereafter his downfall is rapid, and his final moments are as brutal and savage as anything he has inflicted on other people.

n opening word or three about the taxonomy of some of the crime fiction genres I am investigating in these features. Noir has an urban and cinematic origin – shadows, stark contrasts, neon lights blinking above shadowy streets and, in people terms, the darker reaches of the human psyche. Authors and film makers have always believed that grim thoughts, words and deeds can also lurk beneath quaint thatched roofs, so we then have Rural Noir, but this must exclude the kind of cruelty carried out by a couple of bad apples amid a generally benign village atmosphere. So, no Cosy Crime, even if it is set in the Southern states, such as

n opening word or three about the taxonomy of some of the crime fiction genres I am investigating in these features. Noir has an urban and cinematic origin – shadows, stark contrasts, neon lights blinking above shadowy streets and, in people terms, the darker reaches of the human psyche. Authors and film makers have always believed that grim thoughts, words and deeds can also lurk beneath quaint thatched roofs, so we then have Rural Noir, but this must exclude the kind of cruelty carried out by a couple of bad apples amid a generally benign village atmosphere. So, no Cosy Crime, even if it is set in the Southern states, such as  eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or

eal-life rural poverty in the South was by no means confined to former slaves and their descendants. In historical fact, poor white farmers in the Carolinas, for example, were often caught up in a vicious spiral of borrowing from traders and banks against the outcome of their crop; when time came for payback, they were often simply back to zero, or  thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant

thrown off the land due to debt. The rich seam of dirt poor and embittered whites who turn to crime in their anger and resentment has been very successfully mined by novelists. Add a touch of fundamentalist Christianity into the pot and we have a truly toxic stew, such as in Wiley Cash’s brilliant  Her best known novel,

Her best known novel,