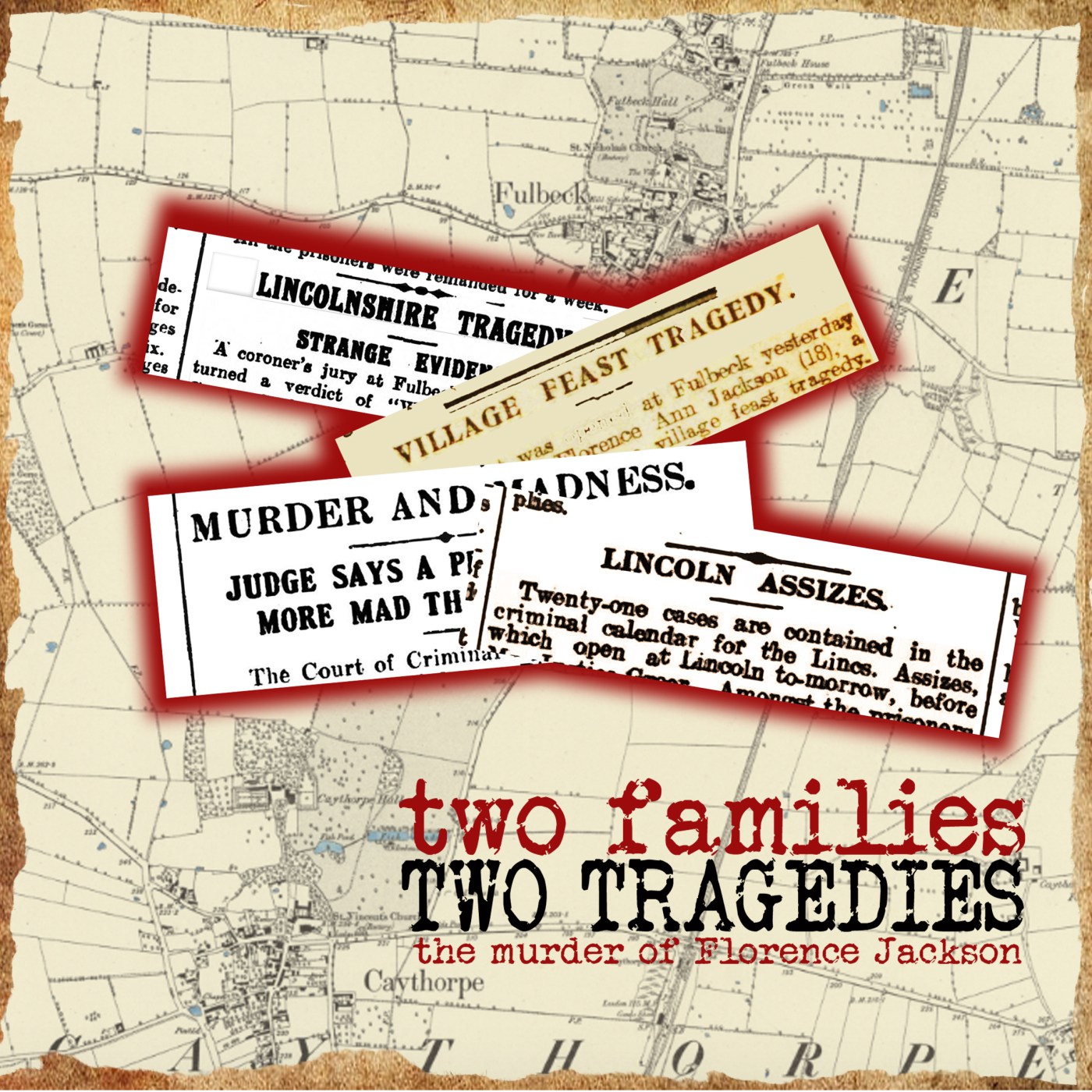

Fulbeck sits amid the hills and hollows of what is known as The Southern Lincolnshire Edge whose most obvious geological feature is the cliff-like ridge which is easy to see when driving along the A17 from Newark. Nearby Leadenham seems to perch on the very edge of this cliff. Fulbeck could almost be mistaken for a Cotswold village, with its abundance of limestone buildings, but most of that stone came from the quarries around Ancaster, just a few miles away. In 1919 the railway ran nearby and there was a station at Caythorpe. These days, the village is bisected by a very busy main road, the A607, which links Leicester and Lincoln. It was just beside this road that the tragedy of the title took place, but our story starts a few years earlier in Grantham, just over ten miles to the south.

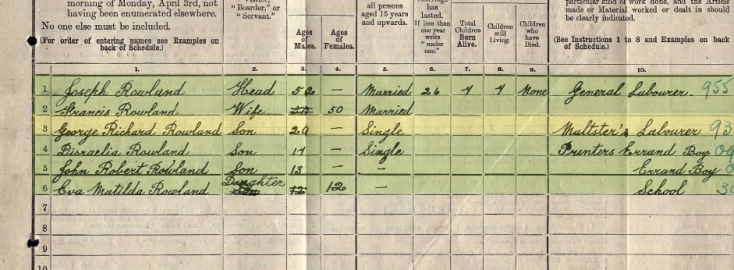

The 1911 census shows that at 50 New Street, a tiny terraced house which still stands, lived the Rowland family.

There was another brother, Joseph William Rowland, but he had left to join the army, and in 1911 was overseas with 1st Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment. By the time war broke out, he had married and was living in Portsmouth. The Rowland family was to pay a heavy price during that war. Both George Richard – known always as Dick – and brother John answered the call of King and Country. Dick joined the Lincolnshire Regiment but John, although he enlisted in Grantham, would go on to serve with The Seaforth Highlanders.

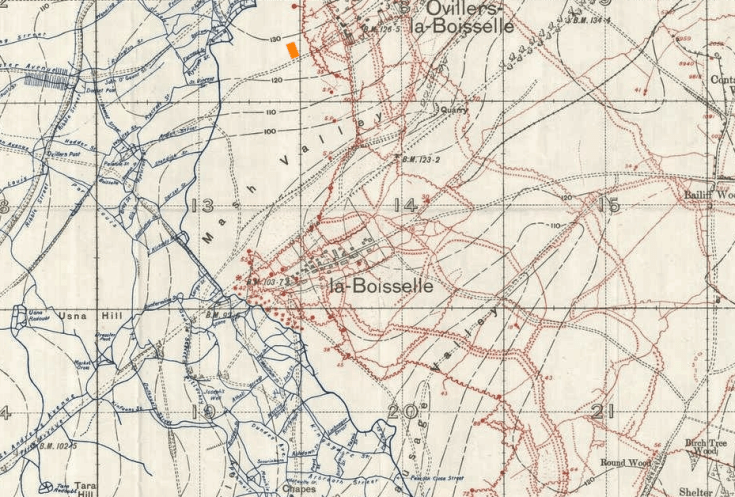

On 1st July 1916, Joseph Rowland was with the 2nd Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment facing the German front lines at Ovillers.

The story of that dreadful day is well known, and not strictly relevant to this story, but suffice it say that Joseph Rowland was one of the 20000 British men killed on that day. A letter would have been delivered to 50 New Street, Grantham, initially saying that Joseph was ‘missing’. Another letter would have followed saying that he was ‘missing, presumed dead’. His body was never found, and his name is one of the 72000 engraved on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

Worse was to follow. Ever anxious to deliver the final crushing blow to the enemy, the British High Command devised yet another huge offensive to punch a hole in German lines. This was to be east of the city of Arras, 20 miles or so north of the Somme killing grounds. The offensive, more properly known as The First Battle of The Scarpe, began at Easter 1917, in a snow storm. Once again, a death notice would find its way to Grantham. This time, although it would have been of little consolation, a body was found and given a decent burial.

Dick returned to Grantham in late 1918, apparently unscathed, at least physically, but we know he had been in action since 1915, and had been both gassed and wounded. Once the euphoria at ‘beating the Hun’ had died away, there was little awaiting men like Dick Rowland in a country that should have been – but wasn’t – grateful. He managed to get work at Rustons in Grantham. On a side note, it is worth remembering that it was at the Ruston works in Lincoln that the first tanks were developed, as well as the iconic aircraft known as the Sopworth Camel.

Now, though, we must return to Fulbeck. Only a grainy newspaper image of Florence Jackson remains, but it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to picture a pretty, round-faced girl with a confident gaze for the camera. Once again, the 1911 census is of service. She lived in Fulbeck with her family. Florence would not live to be noted in the 1921 survey. Opportunities for young women of humble birth in rural communities in those days were limited to farm work, or domestic service. There are suggestions that Florence has been in service at Barkston, or had returned to Fulstow in anticipation of a similar post. At some point she met Dick Rowland, and he was smitten, considering himself deeply in love. He was now 29, with a lifetime of horrors condensed into four years of hell on the Western Front, Florence was just 19, pretty, vibrant and untouched by the death and misery of The Great War.

Now, though, we must return to Fulbeck. Only a grainy newspaper image of Florence Jackson remains, but it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to picture a pretty, round-faced girl with a confident gaze for the camera. Once again, the 1911 census is of service. She lived in Fulbeck with her family. Florence would not live to be noted in the 1921 survey. Opportunities for young women of humble birth in rural communities in those days were limited to farm work, or domestic service. There are suggestions that Florence has been in service at Barkston, or had returned to Fulstow in anticipation of a similar post. At some point she met Dick Rowland, and he was smitten, considering himself deeply in love. He was now 29, with a lifetime of horrors condensed into four years of hell on the Western Front, Florence was just 19, pretty, vibrant and untouched by the death and misery of The Great War.

IN PART TWO

A courtship

A fatal ride on the swing-boats

Gascoigne’s Gate

The Lincoln Assizes

After a few days

After a few days