Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

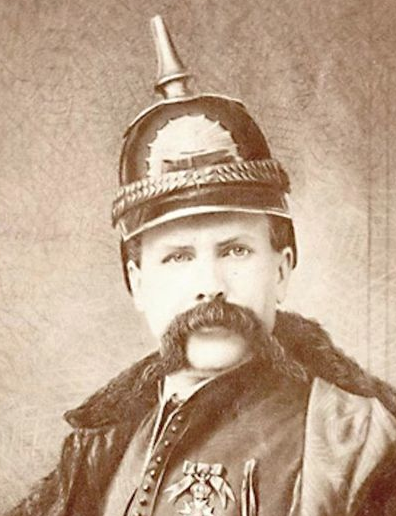

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence.

Historian and broadcaster Tony McMahon (left) sets out his stall in this book, and he is selling a provocative premise. It is that a celebrity fraudster, predatory homosexual, quack doctor and narcissist – Francis Tumblety – was instrumental in two of the greatest murder cases of the 19th century.The first was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, and the second was the murder of five women in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888 – the Jack the Ripper killings.

Tumblety was certainly larger than life. Tall and imposingly built, he favoured dressing up as a kind of Ruritanian cavalry officer, with a pickelhaub helmet, and sporting an immense handlebar moustache. He made – and lost – fortunes with amazing regularity, mostly by selling herbal potions to gullible patrons. Despite his outrageous behaviour, he does not seem to have been a violent man. Yes, he could have been accused of manslaughter after people died from ingesting his elixirs, but apart from once literally booting a disgruntled customer out of his suite, there is no record of extreme physical violence.

Lincoln’s killer John Wilkes Booth and David Herold, a rather dimwitted youth who, along with Mary Suratt and George Azerodt, was hanged for his part in the conspiracy, were certainly known to Tumblety, although there is little evidence that he shared Booth’s Confederate zealotry. Tumblety does not come across as a particularly political animal, although McMahon makes the point that he had friends in high places, who provided him with a ‘get out of jail free’ card on the many occasions when he found himself in court.

Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.

Tumblety (right( was a braggart, a charlatan, a narcissist and a predatory homosexual abuser of young men. Tony McMahon makes this abundantly clear with his exhaustive historical research. What the book doesn’t do, despite it being a thrilling read, is explain why the obnoxious Tumblety made the leap from being what we would call a bull***t artist to the person who killed five women in the autumn of 1888, culminating in the butchery that ended of the life Mary Jeanette Kelly in her Miller’s Court room on the 9th November. Her injuries were horrific, and the details are out there should you wish to look for them. As for Lincoln’s homosexuality – and his syphilis – the jury has been out for some time, with little sign that they will be returning any time soon. McMahon is absolutely correct to say that syphilis was a mass killer. My great grandfather’s death certificate states that he died, aged 48, of General Paralysis of the Insane. Also known as Paresis, this was a euphemistic term for tertiary syphilis. The disease would be contracted in relative youth, produce obvious physical symptoms, and then seem to disappear. Later in life, it would manifest itself in mental incapacity, delusions of grandeur, and physical disability. Lincoln was 56 when he was murdered and, as far as we know, in full command of his senses. I suggest that were Lincoln syphilitic, he would have been unable to maintain his public persona as it appears that he did.

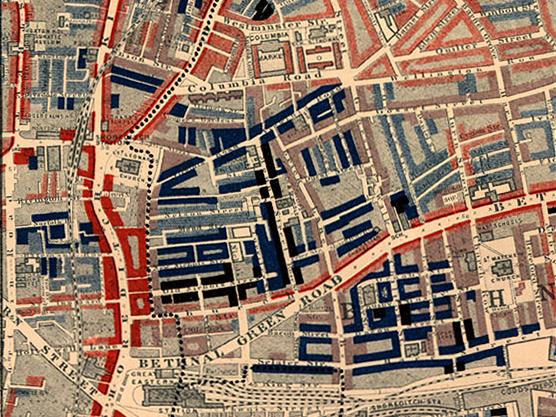

Is Tumblety a credible Ripper suspect? No more and no less than a dozen others. Yes, he was in London when the five canonical murders were committed, but so were, in no particular order, the Duke of Clarence, Neill Cream, Aaron Kosinski, Robert Stephenson, Walter Sickert and Michael Ostrog. Much is made of the fact that Tumblety left the country in some haste, catching a boat across The Channel to Le Havre, and then back to America. He certainly had been in police custody, but for acts of public indecency, and was released on bail, which suggests that the London police did not think he was a danger to the public. The fact is that we will never know. The killings during ‘ The Autumn of Terror’ will forever remain unsolved. At some point, I suppose, the murders will fade into forgetfulness, and books advocating the latest theory will no longer have a market.

The theory that Tumblety also suffered from syphilis could account for the insane rage with which Marie Jeanette Kelly was butchered, but we must bear in mind that Tumblety lived until he was 70, dying in St Louis in May 1903, apparently from a heart attack. This said, Tony McMahon has written a wonderfully entertaining book with an excellent narrative drive, and a jaw-dropping insight into the demi-monde of mid-19th century America. McMahon’s research is beyond question, and he provides extensive footnotes and very useful index. The cover blurb says, “One man links the two greatest crimes of the 19th century.” Tony McMahon establishes beyond dispute that Francis Tumblety was that man. Whether he proves that he was responsible for either is another matter altogether.

Kelly, met a bloody end in her Millers Court hovel. Of Brewer, we know very little, but his style can best be illustrated with a brief extract.

Kelly, met a bloody end in her Millers Court hovel. Of Brewer, we know very little, but his style can best be illustrated with a brief extract. Belloc-Lowndes (right) was the older sister of the prolific writer and poet Hilaire Belloc, but she avoided her brother’s antimodern polemicism, and wrote biographies, plays – and novels which were very highly thought of for their subtlety and psychological insight into crime, although she preferred not to be thought of as a crime fiction writer. In The Lodger, Mr and Mrs Bunting have staked their life savings on buying a house big enough to take in paying guests, but just as their dream is on the verge of crumbling, salvation comes in the form of the mysterious Mr Sleuth, who knocks on the door and takes a room, paying up front with many a gold sovereign. As Mr and Mrs Bunting count their money – and their blessings – London is gripped with terror as a killer nicknamed ‘The Avenger’ stalks the streets searching for blood. The Buntings’ peace of mind evaporates as they suspect that their lodger is none other than The Avenger. Such is the quality of The Lodger that it has been filmed many times, most notably by Alfred Hitchcock in 1927. It would be remiss of me not to quote the famous bloodcurdling imprecation at the end of the book, directed at the hapless landlady.

Belloc-Lowndes (right) was the older sister of the prolific writer and poet Hilaire Belloc, but she avoided her brother’s antimodern polemicism, and wrote biographies, plays – and novels which were very highly thought of for their subtlety and psychological insight into crime, although she preferred not to be thought of as a crime fiction writer. In The Lodger, Mr and Mrs Bunting have staked their life savings on buying a house big enough to take in paying guests, but just as their dream is on the verge of crumbling, salvation comes in the form of the mysterious Mr Sleuth, who knocks on the door and takes a room, paying up front with many a gold sovereign. As Mr and Mrs Bunting count their money – and their blessings – London is gripped with terror as a killer nicknamed ‘The Avenger’ stalks the streets searching for blood. The Buntings’ peace of mind evaporates as they suspect that their lodger is none other than The Avenger. Such is the quality of The Lodger that it has been filmed many times, most notably by Alfred Hitchcock in 1927. It would be remiss of me not to quote the famous bloodcurdling imprecation at the end of the book, directed at the hapless landlady.

Colin Wilson, who died in 2013, (left) was the kind of man with whom the British establishment, certainly in the 1950s and 60s, was most deeply ill at ease. He was, as much by his own proclamation as that of others, intellectually formidable. He burst on the literary scene in 1957 with The Outsider, a journey through an existential world in the company of, among others, Camus, Nietzsche, Kafka, Sartre, Hermann Hesse and Van Gogh. His novel that concerns us is Ritual In The Dark. Published, after a long gestation, in 1960, it examines how The Ripper legend transposes itself onto the London streets of the late 1950s. It must be remembered that many of the murder sites were still more or less recognisable, at that time, to Ripper afficionados. The tale involves three young men, Gerard Sorme, Oliver Glasp and Austin Nunne. Sorme goes about his life well aware of the significance of past deeds, but also knowing that a present day killer is out and about, emulating the horrors of 1888. Wilson could be said to be one of the pioneers of psychogeography, a linking of past and present much used by modern writers such as Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd. Sorme says,

Colin Wilson, who died in 2013, (left) was the kind of man with whom the British establishment, certainly in the 1950s and 60s, was most deeply ill at ease. He was, as much by his own proclamation as that of others, intellectually formidable. He burst on the literary scene in 1957 with The Outsider, a journey through an existential world in the company of, among others, Camus, Nietzsche, Kafka, Sartre, Hermann Hesse and Van Gogh. His novel that concerns us is Ritual In The Dark. Published, after a long gestation, in 1960, it examines how The Ripper legend transposes itself onto the London streets of the late 1950s. It must be remembered that many of the murder sites were still more or less recognisable, at that time, to Ripper afficionados. The tale involves three young men, Gerard Sorme, Oliver Glasp and Austin Nunne. Sorme goes about his life well aware of the significance of past deeds, but also knowing that a present day killer is out and about, emulating the horrors of 1888. Wilson could be said to be one of the pioneers of psychogeography, a linking of past and present much used by modern writers such as Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd. Sorme says, “I am lying here in the middle of London, with a population of three million people asleep around me,

“I am lying here in the middle of London, with a population of three million people asleep around me,

KINDLE ROUNDUP, JULY 25th 2016. It has to be said, for all that it’s a wonderful invention, and has revolutionised reading, The Kindle (other devices are available!) can provide a pitfall for the book reviewer. While a physical To Be Read pile is ever visible, and sits in the corner looking at you in an accusing fashion, the equivalent stack of books on the digital reader quietly goes away when the power is turned off. So, with apologies to the writers and publishers who have trusted me with their offspring, here is my first, but belated, look at some great titles.

KINDLE ROUNDUP, JULY 25th 2016. It has to be said, for all that it’s a wonderful invention, and has revolutionised reading, The Kindle (other devices are available!) can provide a pitfall for the book reviewer. While a physical To Be Read pile is ever visible, and sits in the corner looking at you in an accusing fashion, the equivalent stack of books on the digital reader quietly goes away when the power is turned off. So, with apologies to the writers and publishers who have trusted me with their offspring, here is my first, but belated, look at some great titles. Mercedes Marie by Fusty Luggs

Mercedes Marie by Fusty Luggs No Accident by Robert Crouch

No Accident by Robert Crouch Falling Suns by J.A. Corrigan

Falling Suns by J.A. Corrigan The Woman In The Woods by Louise Mullins

The Woman In The Woods by Louise Mullins Unquiet Souls by Liz Mistry

Unquiet Souls by Liz Mistry