Some critics have compared Anthony Rhodes (1916-2004) with his more illustrious near contemporary, Evelyn Waugh. They were both Roman Catholics, although Rhodes converted late in life. Both wrote novels, biographies and travel books. Both – and this is most relevant here – wrote fictionalised accounts of their service in WW2. Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy – Men at Arms, Officers and Gentlemen & Unconditional Surrender – was a much more substantial achievement, but both wrote from the view of public school educated men who had gone on to higher education, in Waugh’s case Oxford, and in Rhodes’s case Royal Military College Sandhurst. The latter, of course, makes Rhodes a professional soldier, but they both wrote with a certain sardonic detachment about the war and the soldiers who served in it.

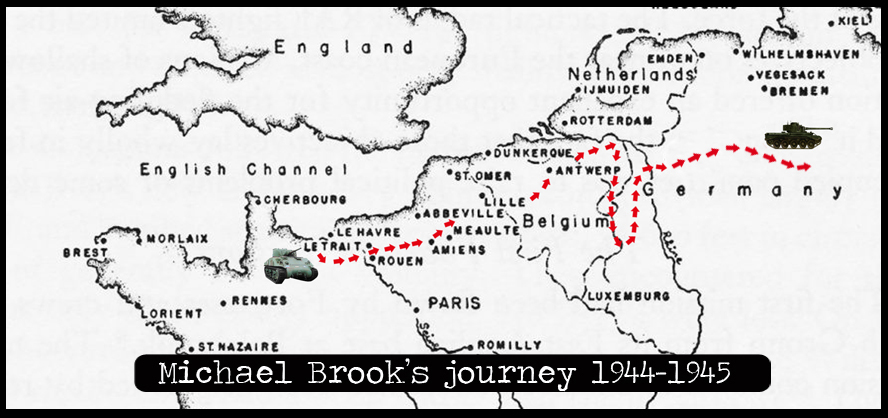

Sword of Bone begins in the early autumn of 1939 when Rhodes becomes a liaison officer for his army division. He is a gifted linguist, and he is a member of the advance party sent to France. They assemble in Southampton, then:

“At three o’clock that afternoon we embarked on a miserable grimy little cross-channel boat called The Duchess of Atholl, which had been painted a dirty grey and which, except for what appeared to be an inexplicable pair of blue knickers drying on the bridge, had little enough connection with her eponymous aristocrat.”

His party work their way at a leisurely pace from Brittany up to the grim and grey slag heaps and factory chimneys in the region of Lille, Lens and La Bassée. His role eventually settles into that of commissioning supplies of engineering materials – principally those needed to meet a sudden demand for concrete pill boxes.

His party work their way at a leisurely pace from Brittany up to the grim and grey slag heaps and factory chimneys in the region of Lille, Lens and La Bassée. His role eventually settles into that of commissioning supplies of engineering materials – principally those needed to meet a sudden demand for concrete pill boxes.

It is worth spelling out at this stage what exactly was going on in the war in Western Europe. On 3rd September 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany as a result of Hitler’s invasion of Poland. All through that autumn, until the winter became spring, there was little or no military action on the ground. In December, British warships had engaged the German Battleship Graf von Spee, and forced it to seek refuge in the neutral port of Montivideo, where it was eventually scuttled. Back in France, the French had the largest army in Europe, the best tanks, and were convinced that the complex of fortifications known as The Maginot Line made its eastern border with Germany impregnable.

Not so secure, as Rhodes finds when he is billeted near Lille, is the border with Belgium – little more than a few strands of barbed wire and sentry boxes manned by a handful of bored soldiers. The first half of the book is a series of entertaining encounters with village Mayors, profiteering restaurateurs, blimpish Colonels and the complex hierarchies that exist between different parts of the British Army. In Rhodes’s entourage are other officers, of contrasting temperament and character. There is Stimpson, intellectual, effete, almost, and politically rather ‘unsound’.

“When the last politician has been strangled with the entrails of the last general, then, and only then, shall we have peace“, he says one evening in the Mess.

The Padre is emphatically different. He is “a man whose views on the treatment of Indians did more credit to Kipling than to his cloth.“

Rhodes catches sight of his first German (through binoculars) when he and other officers visit a Maginot fort near Veckering, in the Moselle region. Rhodes’s Major wants action:

“Quick, ” said Major Cairns, turning to a Guardsman with a rifle, “Pick him off. Quickly, man.”

“Please, ” said the subaltern, without moving, “do no such thing. Our business is to obtain information. We want prisoners, not dead men. Besides, if we fire from here, it will only give our own position away. I am afraid I must ask you not to think of firing, sir. It will only mean an immediate reply from the Boche with mortar fire.”

Major Cairns sadly put down the rifle which he had taken from the Guardsman, and we all stood by the trees looking out over the valley.”

Of course, the fun has to end sometime, and after a foray into Norway, Hitler’s forces invade Holland Belgium and France on 10th May. The citizens of Louvain and Brussels, remembering the heroics of two decades earlier, are convinced that the ‘Tommies’ will, once again, give the Boche a bloody nose. As we all know, it was not to be. The Germans have ignored the Maginot Line and are storming down through Belgium. Arras falls, and the French army – on paper, numerically and technically superior – are in headlong retreat along with their British allies. It is very much a case of “our revels now are ended” for Rhodes and his colleagues.

Sword of Bone is a little masterpiece. As it follows the fortunes of a small group of British Army officers in the early days of WW2, it records their journey from champagne and lobster lunches and a seemingly absent enemy, to the terrifying and bloodstained beaches of Dunkirk. Rhodes writes with great charm, gentle satire, pinpoint observation but with total authenticity. The book is published by the Imperial War Museum and is out now.

You can read my reviews of the other books in this excellent series by clicking the image below.

TO ALL THE LIVING . . . Between the covers

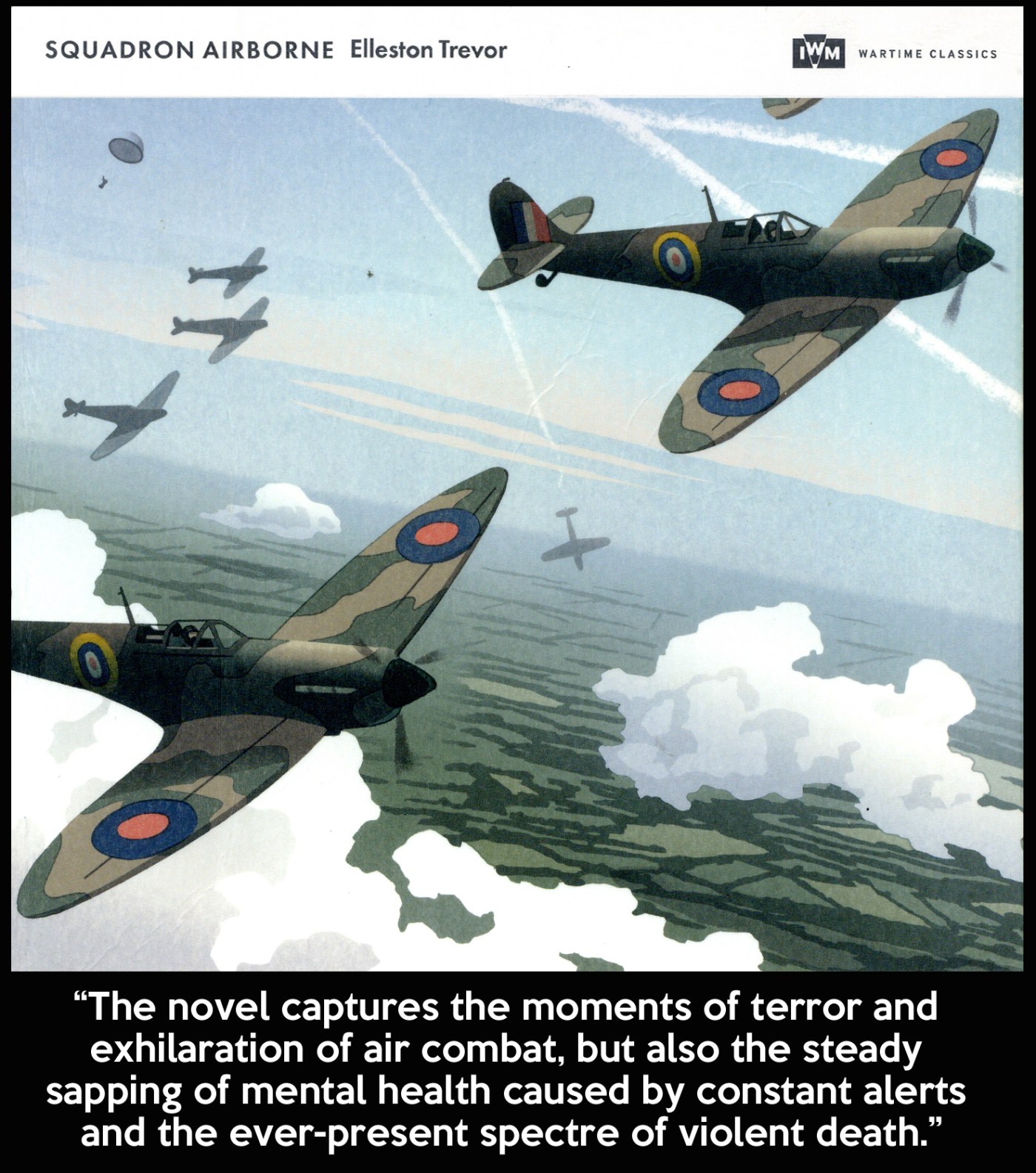

This is the latest in the series of excellent reprints from the Imperial War Museum. They have ‘rediscovered’ novels written about WW2, mostly by people who experienced the conflict either home or away. Previous books can be referenced by clicking this link.

We are, then, immediately into the dangerous territory of judging creative artists because of their politics, which never ends well, whether it involves the Nazis ‘cancelling’ Mahler because he was Jewish or more recent critics shying away from Wagner because he was anti-semitic and, allegedly, admired by senior figures in the Third Reich. The longer debate is for another time and another place, but it is an inescapable fact that many great creative people, if not downright bastards, were deeply unpleasant and misguided. To name but a few, I don’t think I would have wanted to list Caravaggio, Paul Gauguin, Evelyn Waugh, Eric Gill or Patricia Highsmith among my best friends, but I would be mortified not to be able to experience the art they made.

So, could Monica Felton write a good story, away from hymning the praises of KIm Il Sung and his murderous regime? To All The Living (1945) is a lengthy account of life in a British munitions factory during WW2, and is principally centred around Griselda Green, a well educated young woman who has decided to do her bit for the country. To quickly answer my own question, the answer is a simple, “Yes, she could.”

Another question could be, “Does she preach?“ That, to my mind, is the unforgivable sin of any novelist with strong political convictions. Writers such as Dickens and Hardy had an agenda, certainly, but they subtly inserted this between the lines of great story-telling. Felton is no Dickens or Hardy, but she casts a wry glance at the preposterous bureaucracy that ran through the British war effort like the veins in blue cheese. She highlights the endless paperwork, the countless minions who supervised the completion of the bumf, and the men and women – usually elevated from being section heads in the equivalent of a provincial department store – who ruled over the whole thing in a ruthlessly delineated hierarchy.

Amid the satire and exaggerated portraits of provincial ‘jobsworths’ there are darker moments, such as the descriptions of rampant misogyny, genuine poverty among the working classes, and the very real chance that the women who filled shells and crafted munitions – day in, day out – were in danger of being poisoned by the substances they handled. The determination of the factory managers to keep these problems hidden is chillingly described. These were rotten times for many people in Britain, but if Monica Felton believed that things were being done differently in North Korea or the USSR, then I am afraid she was sadly deluded.

The social observation and political polemic is shot through with several touches or romance, some tragedy, and the mystery of who Griselda Green really is. What is a poised, educated and well-spoken young woman doing among the down-to-earth working class girls filling shells and priming fuzes?

My only major criticism of this book is that it’s perhaps 100 pages too long. The many acerbic, perceptive and quotable passages – mostly Felton’s views on the more nonsensical aspects of British society – tend to fizz around like shooting stars in an otherwise dull grey sky.

Is it worth reading? Yes, of course, but you must be prepared for many pages of Ms Felton being on communist party message interspersed with passages of genuinely fine writing. To All The Living is published by the Imperial War Museum, and is out now.