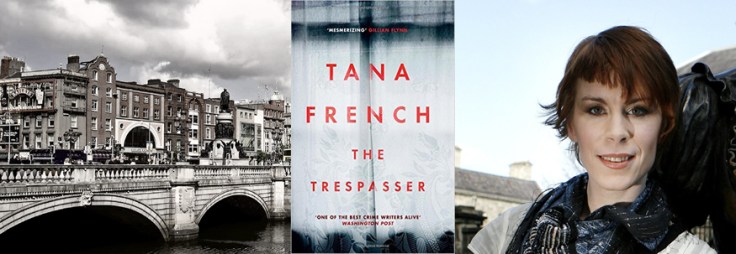

AUTHOR TANA FRENCH beams us down into an endlessly wet, chill and foggy Dublin. The old working class district of Stoneybatter has become, so we are told elsewhere, the epitome of ‘cool’ with all the trappings which that entails – craft ales, artisan bakeries and community spaces. There’s little of that on display when DI Antoinette Conway and her partner Steve Moran are called to a terrace house to view the body of a dead woman. Aislinn Murray is on the floor by her fake rustic fireplace with severe head injuries. Conway says;

“Her face is covered by blond hair, straightened and sprayed so ferociously that even murder hasn’t managed to mess it up. She looks like Dead Barbie.”

Two things puzzle Conway and Moran. Firstly, who was the man who made the ‘phone call alerting the authorities to Aislinn’s demise, and why did he call direct to Stoneybatter police station, rather than using the emergency number? Secondly who was the dead woman’s intended dinner guest that evening? The table was laid for two, with candles lit and a bottle of decent red wine quietly breathing.

As Conway puts her team of ‘D’s’ – murder detectives – together, we learn that she has a prickly relationship with her fellow officers. Yes, she is a woman and, yes, the men’s laddish behaviour – nothing new to readers of novels featuring women detectives – is nastier than simple banter, but the dystopian atmosphere in the squad room is more complex. To be blunt, Conway is something of a pain in the arse at times. She has more chips on her shoulder than a bag of McCains (other brands are available), and the endless baiting and crass pranks from her male colleagues simply stoke the fires of bitterness. Having said that, she is an absolutely pin bright and razor sharp copper, but her fragile equanimity is not helped when her boss forces her to work alongside DI Breslin, a man she loathes. Breslin is glib, sharp-suited and much admired by the other D’s. In short, he is everything that Conway is not.

The consensus among the Gardaí is that the killer of Aislinn Murray is her latest boyfriend, an apparently mild-mannered bookshop owner called Rory Fallon, and he was the intended beneficiary of the candle-lit dinner in the Stoneybatter cottage. From the moment Conway clapped eyes on the Aislinn’s ruined face, however, she is tantalised by a feeling that she has seen the girl before. When that memory clicks into place, the investigation takes a different turn entirely, and it turns over a large rock which has many nasty creatures scuttling around underneath it.

To say that The Trespasser is a police procedural is, strictly speaking, accurate. But the description does the book justice in the same way that simply describing Luciano Pavarotti as a singer fails to illuminate the central truth. Tana French knows her Dublin, and she knows her An Garda Síochána, but those dabs of authenticity are just that – mere paint spots on a subtle, complex and magnificent canvas.

I suppose I must have drawn breath during the five or six minutes it took to read the gripping climax of this book, but I don’t remember doing so. The final pages contain no action to speak of, just four people sitting in an office, but the psychological intensity is quite terrifying. The quality of the writing is such that French does not allow Conway to luxuriate in her victory, such as it is. There is just a terrible sense of pity, of shattered lives, and human frailty. Conway walks away from the police station:

“The cobblestones feel wrong under my feet, thin skins of stone over bottomless fog. The squad I’ve spent the last two years hating, the sniggering fucktards backstabbing the solo warrior while she fought her doomed battle; that’s gone, peeled away like a smeared film that was stuck down hard over the real thing.”

This is a brilliant, savage and uncomfortable read. Don’t pick it up unless you want your emotions scoured and your sense of empathy and compassion put through the mangle.

Tana French has her own website, and you can follow the link to check buying choices for The Trespasser, which is available now.

There are few grander places in Dublin’s fair city than Leinster House, even though its style and grandeur might hark back to the days when the Irish aristocracy – with its links to England – were a power in the land. Whether the current inhabitants of the ducal mansion do its stately rooms and grand corridors proud is not for me to judge, for it houses Oireachtas Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic. There must have been a whole lexicon of killing words uttered between political opponents over the decades, but few – if any – actual murders have despoiled the Georgian grandeur. Jo Spain puts this right within the first few pages of Beneath The Surface.

There are few grander places in Dublin’s fair city than Leinster House, even though its style and grandeur might hark back to the days when the Irish aristocracy – with its links to England – were a power in the land. Whether the current inhabitants of the ducal mansion do its stately rooms and grand corridors proud is not for me to judge, for it houses Oireachtas Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic. There must have been a whole lexicon of killing words uttered between political opponents over the decades, but few – if any – actual murders have despoiled the Georgian grandeur. Jo Spain puts this right within the first few pages of Beneath The Surface. IRISH CRIME FICTION seems to be on a roll at the moment. With writers like Anthony Quinn, Stuart Neville, Ken Bruen, John McAllister and Sinead Crowley making headlines, it’s not too fanciful to see Ireland – North and South – rivaling its neighbour across the sea, Scotland, as everyone’s favourite setting for moody and intense crime tales. Is there room for one more at the top table of Irish crime? There certainly is, when it’s Jo Spain asking for a seat. Her debut novel

IRISH CRIME FICTION seems to be on a roll at the moment. With writers like Anthony Quinn, Stuart Neville, Ken Bruen, John McAllister and Sinead Crowley making headlines, it’s not too fanciful to see Ireland – North and South – rivaling its neighbour across the sea, Scotland, as everyone’s favourite setting for moody and intense crime tales. Is there room for one more at the top table of Irish crime? There certainly is, when it’s Jo Spain asking for a seat. Her debut novel

Stuart Neville (left) returns with another hard-bitten and edgy tale of life and crimes in Northern Ireland. Set in a fictional village on the edge of Belfast, we are reunited with DCI Serena Flanagan, who first appeared in Those We Left Behind. Like much of life in Ulster, fictional and real, religion and the stresses and strains it places on secular life is never far from the surface. The sacred influence in this case is provided by the Reverend Peter McKay. The clergyman is a widower, but we find that he has been taking his parochial duties above and beyond what is normally expected. The recipient of his pastoral care is Roberta, the attractive wife of Henry Garrick.

Stuart Neville (left) returns with another hard-bitten and edgy tale of life and crimes in Northern Ireland. Set in a fictional village on the edge of Belfast, we are reunited with DCI Serena Flanagan, who first appeared in Those We Left Behind. Like much of life in Ulster, fictional and real, religion and the stresses and strains it places on secular life is never far from the surface. The sacred influence in this case is provided by the Reverend Peter McKay. The clergyman is a widower, but we find that he has been taking his parochial duties above and beyond what is normally expected. The recipient of his pastoral care is Roberta, the attractive wife of Henry Garrick.