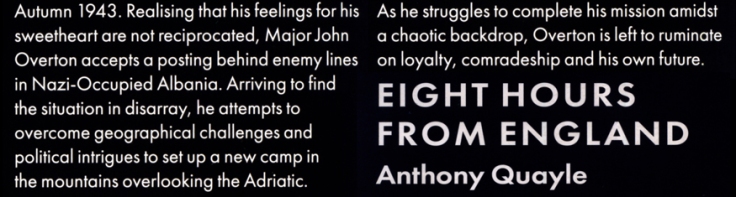

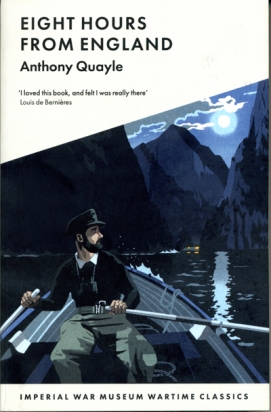

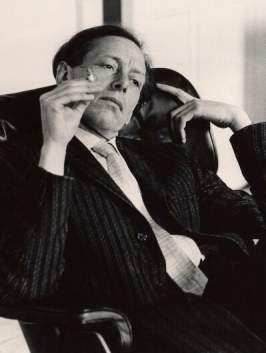

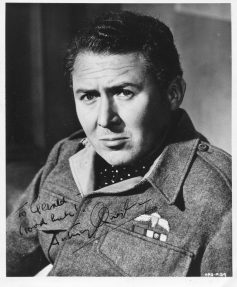

To many of us who grew up in the 1950s Anthony Quayle was to become one of a celebrated group of theatrical knights, along with Olivier, Gielgud, Richardson and Redgrave. Until recently I had no idea that he was also wrote two novels based on his experiences in WW2. The first of these, Eight Hours From England was first published in 1945 and is the fourth and final reprint in the impressive series from the Imperial War Museum.

To many of us who grew up in the 1950s Anthony Quayle was to become one of a celebrated group of theatrical knights, along with Olivier, Gielgud, Richardson and Redgrave. Until recently I had no idea that he was also wrote two novels based on his experiences in WW2. The first of these, Eight Hours From England was first published in 1945 and is the fourth and final reprint in the impressive series from the Imperial War Museum.

Major John Overton, stoically unlucky in love, combines a rather self-sacrificial gesture with a genuine desire to be at ‘the sharp end’ of the war. He chases up casual acquaintances working in the chaotic bureaucracy of London military administration and, rather randomly, finds himself sent out to Albania in the final days of December 1943. The chaotic country – ruled until 1939 by the improbably-named King Zog – had then been annexed by Mussolini’s Italy but after Italy’s surrender to the Allies in the autumn of 1943, German forces had moved in and had a tenuous grip of the country.

The brief of Britain’s SOE – the Special Operations Executive – was to fan the flames of behind-the-lines resistance in occupied countries. Admirer’s of Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy will recall that in Unconditional Surrender Guy Crouchback is sent to co-ordinate similar activities in nearby Yugoslavia but, like Crouchback, Overton finds that the situation on the ground is far from straightforward. On the one hand are the Communist partisans, but on the other are the Balli Kombëtar, a fiercely nationalist group who hate the Communists just as much as they hate the Nazis.

New Year’s day 1944 brings little physical comfort to Overton, but he is determined to make a difference and, above all, wants to take the war to the Germans. In the following weeks and months he meets unexpected obstacles, chief among them being the Albanians themselves. Their character baffles him. He remarks, ruefully.

“The misfortunes of others were the only jokes at which Albanians laughed, the height of comedy being when another man was killed.”

His courage, tenacity and sheer physical resilience are immense, but are sorely tried. Overton’s private thoughts are never far from England:

“I stayed a while longer looking out over the grey Adriatic where in the distance, the island of Corfu was dimly visible between the rain squalls. It was an afternoon on which to recall the hissing of logs in the hearth of an English home and the sound of the muffin-man’s bell in the street outside.”

Of the three classic reprints which feature overseas action Eight Hours From England is the bleakest by far. The books by Alexander Baron and David Piper bear solemn witness to the deaths of brave men, sometimes heroic but often simply tragic: the irony is that Overton and his men do not, as far as I can recall, actually fire a shot in anger. No Germans are killed as a result of their efforts; the Allied cause is not advanced by the tiniest fraction; their heartbreaking struggle is not against the swastika and all it stands for, but against a brutally inhospitable terrain, bitter weather and, above all, the distrust, treachery and embedded criminality of many of the Albanians they encounter.

Of the three classic reprints which feature overseas action Eight Hours From England is the bleakest by far. The books by Alexander Baron and David Piper bear solemn witness to the deaths of brave men, sometimes heroic but often simply tragic: the irony is that Overton and his men do not, as far as I can recall, actually fire a shot in anger. No Germans are killed as a result of their efforts; the Allied cause is not advanced by the tiniest fraction; their heartbreaking struggle is not against the swastika and all it stands for, but against a brutally inhospitable terrain, bitter weather and, above all, the distrust, treachery and embedded criminality of many of the Albanians they encounter.

Overton survives, after a fashion, but is close to physical and spiritual breakdown. The heartache which prompted his original gesture is not eased, and the method of his dismissal by the young woman provides a cruel final metaphor:

“I put my hand into my pocket and pulled out what I thought was my handkerchief. But it was not: it was Ann’s letter. The blue writing paper had gone pulpy; the writing had smeared and wriggled across the page. Not a word was now legible.”

Quite early in the book, when Overton reaches Albania to replace the badly wounded former senior officer, the sick man makes a prophetic statement as he is stretchered aboard the boat to take him to safety:

“For a moment Keith did not speak and I thought he had not heard me, then the lips moved and he said slowly, and very clearly:

‘I wish you joy of the damned place.’”

Click on the covers below to read my reviews of the other three IWM classic reprints.

his 1943 novel by Kathleen Hewitt is the third in the excellent series of Imperial War Museum reprints of wartime classics, but couldn’t be more different from the first two,

his 1943 novel by Kathleen Hewitt is the third in the excellent series of Imperial War Museum reprints of wartime classics, but couldn’t be more different from the first two,  A jolly murder? Well, of course. Fictional murders can be range from brutal to comic depending on the genre, and although the corpse found in the back garden of Mrs Meake’s lodging house – 15 Terrapin Road – is just as dead as any described by Val McDermid or Michael Connelly, the mood is set by the chief amateur investigator, a breezy and frightfully English RAF pilot called David Heron on recuperation leave from his squadron, and his elegantly witty lady friend Tess. He is from solid county stock:

A jolly murder? Well, of course. Fictional murders can be range from brutal to comic depending on the genre, and although the corpse found in the back garden of Mrs Meake’s lodging house – 15 Terrapin Road – is just as dead as any described by Val McDermid or Michael Connelly, the mood is set by the chief amateur investigator, a breezy and frightfully English RAF pilot called David Heron on recuperation leave from his squadron, and his elegantly witty lady friend Tess. He is from solid county stock: eaders will not need a degree in 20th century social history to recognise that the book’s title refers to the methods used by shopkeepers to circumvent the official rationing of food and fancy goods. More sinister is the presence – both in real life and in the book – of criminals who exploit the shortages to make serious money playing the black market and for whom deadly violence is just a way of life.

eaders will not need a degree in 20th century social history to recognise that the book’s title refers to the methods used by shopkeepers to circumvent the official rationing of food and fancy goods. More sinister is the presence – both in real life and in the book – of criminals who exploit the shortages to make serious money playing the black market and for whom deadly violence is just a way of life.

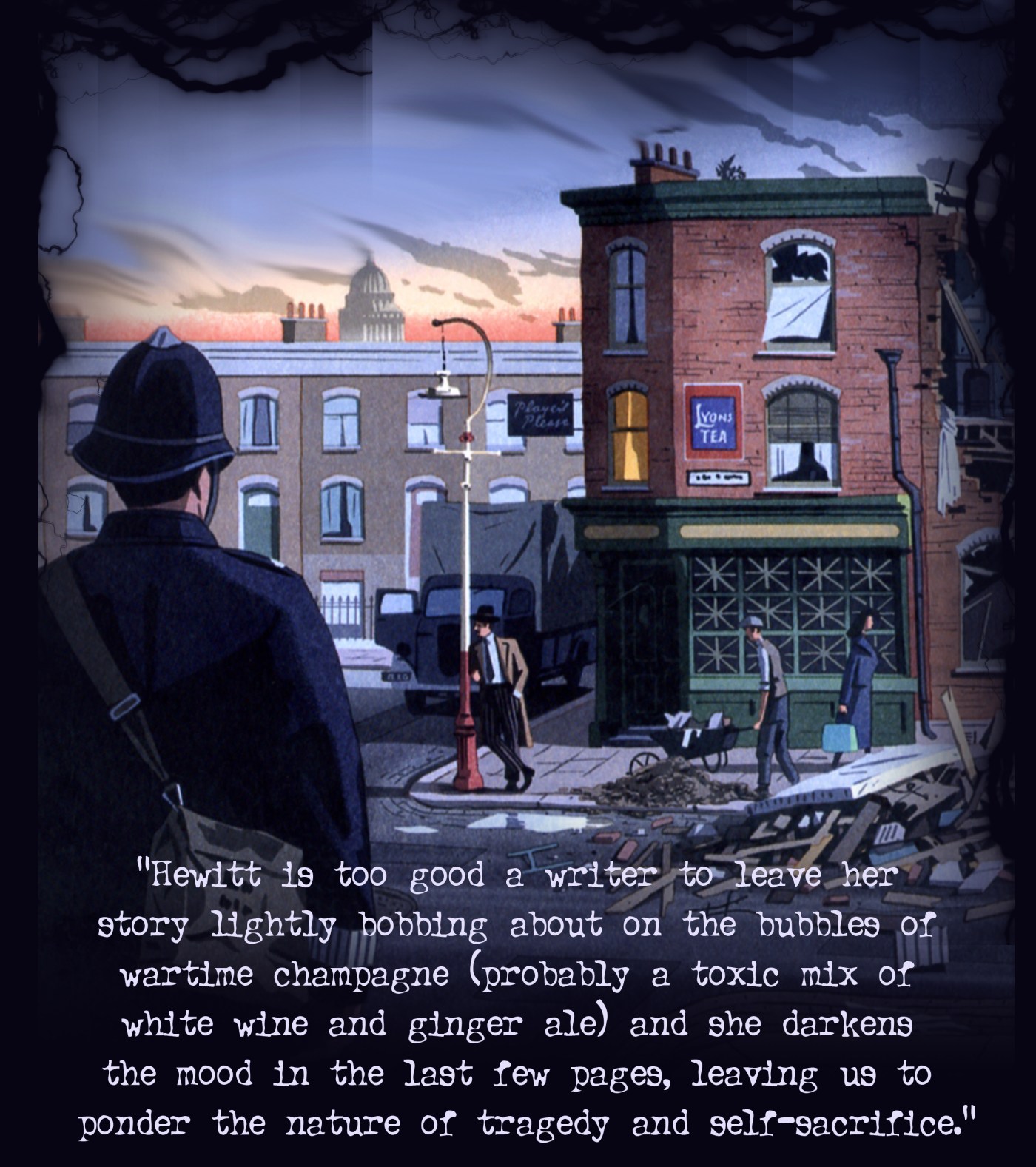

The story rattles along in fine style as the hours tick by before David has to return to the war. He has two pressing needs. One is to buy the special licence which will enable him to marry Tess, and the other is to find the Terrapin Road murderer. Hewitt (right) is too good a writer to leave her story lightly bobbing about on the bubbles of wartime champagne (probably a toxic mix of white wine and ginger ale) and she darkens the mood in the last few pages, leaving us to ponder the nature of tragedy and self-sacrifice.

The story rattles along in fine style as the hours tick by before David has to return to the war. He has two pressing needs. One is to buy the special licence which will enable him to marry Tess, and the other is to find the Terrapin Road murderer. Hewitt (right) is too good a writer to leave her story lightly bobbing about on the bubbles of wartime champagne (probably a toxic mix of white wine and ginger ale) and she darkens the mood in the last few pages, leaving us to ponder the nature of tragedy and self-sacrifice.

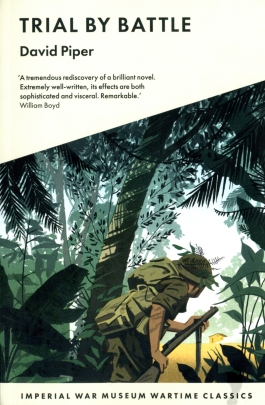

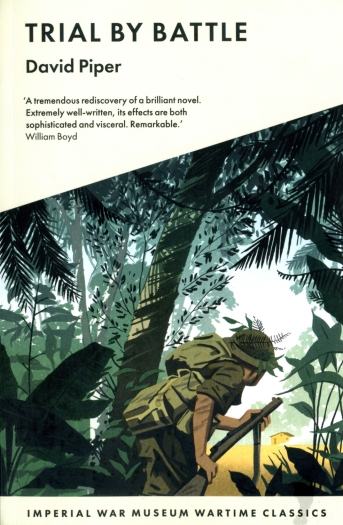

lan Mart is a bookish, completely unmiitary young man who, fresh from Cadet College, is posted as a Second Lieutenant to an Indian Army Battalion in the autumn of 1941. The Japanese army is on the move, but are still believed to be just swarms of little yellow men who will melt away when faced with troops led by decent British officers. Mart is taken under the wing of Acting Captain Sam Holl:

lan Mart is a bookish, completely unmiitary young man who, fresh from Cadet College, is posted as a Second Lieutenant to an Indian Army Battalion in the autumn of 1941. The Japanese army is on the move, but are still believed to be just swarms of little yellow men who will melt away when faced with troops led by decent British officers. Mart is taken under the wing of Acting Captain Sam Holl: The figure of Sam Holl struck an immediate chord with me, and I wondered momentarily where I had met him before. He is a more warlike version of Guy Crouchback’s brother in arms, Apthorpe. In Men At Arms (1951) and Officers And Gentlemen (1955) Evelyn Waugh gives us a pompous and priggish chap with completely bogus military and social airs and graces. He invites us to scorn Apthorpe and his pretensions while slyly revealing the pathos of Apthorpe’s real identity; probably an orphan, brought up by an elderly aunt; sent to a very minor public school, and packed of, virtually penniless, to serve in some down at heel colonial service. When Apthorpe dies in hospital as a result of Crouchback having smuggled him a bottle of whisky, the comedy turns to tragedy, and our mockery turns to shame-faced guilt.

The figure of Sam Holl struck an immediate chord with me, and I wondered momentarily where I had met him before. He is a more warlike version of Guy Crouchback’s brother in arms, Apthorpe. In Men At Arms (1951) and Officers And Gentlemen (1955) Evelyn Waugh gives us a pompous and priggish chap with completely bogus military and social airs and graces. He invites us to scorn Apthorpe and his pretensions while slyly revealing the pathos of Apthorpe’s real identity; probably an orphan, brought up by an elderly aunt; sent to a very minor public school, and packed of, virtually penniless, to serve in some down at heel colonial service. When Apthorpe dies in hospital as a result of Crouchback having smuggled him a bottle of whisky, the comedy turns to tragedy, and our mockery turns to shame-faced guilt. espite Alan Mart being our eyes and ears as the real war gets nearer and nearer to the battalion, Holl is, literally and metaphorically, a towering figure. He has the worst aspects of the blinkered British imperialist, but he displays immense physical courage. His bluster, near alcoholism and debased view of native women contrast poignantly with moments of extreme social vulnerability:

espite Alan Mart being our eyes and ears as the real war gets nearer and nearer to the battalion, Holl is, literally and metaphorically, a towering figure. He has the worst aspects of the blinkered British imperialist, but he displays immense physical courage. His bluster, near alcoholism and debased view of native women contrast poignantly with moments of extreme social vulnerability: hen Mart and Holl reach Malaya they learn many things, few if any of them to their advantage. The sparkling new radio sets abjectly refuse to work over any distance further than the line of sight and, more disturbing still, the despised little yellow men are resolutely disinclined to scatter at the bark of a British military command. Quite the reverse; they are numerous, well trained, superbly equipped, utterly remorseless and, seemingly, irresistible.

hen Mart and Holl reach Malaya they learn many things, few if any of them to their advantage. The sparkling new radio sets abjectly refuse to work over any distance further than the line of sight and, more disturbing still, the despised little yellow men are resolutely disinclined to scatter at the bark of a British military command. Quite the reverse; they are numerous, well trained, superbly equipped, utterly remorseless and, seemingly, irresistible. David Piper’s biography is covered comprehensively in the publicity for this series, so suffice it to say he writes of what he knows. I am reminded of the lines from the old hymn;

David Piper’s biography is covered comprehensively in the publicity for this series, so suffice it to say he writes of what he knows. I am reminded of the lines from the old hymn;

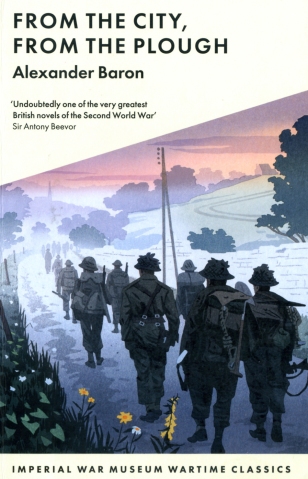

his 1948 best seller echoes Alexander Baron’s own military career as it follows a battalion of a fictional infantry brigade as they prepare for – and then take part in – D Day in the summer of 1944. The Fifth Wessex is, as the book’s title suggests, made up of a mixture of clumsy red-cheeked farm boys from the chalk uplands, well-read introverts who keep themselves to themselves, streetwise chancers and bewildered lads who are virgins in both bedroom and battlefield. They could be soldiers from earlier wars, and their ancestors might have known Agincourt, Marston Moor, Malplaquet, Talavera, Spion Kop and Arras. Baron has no time for the thinly veiled homo-eroticism of some of the Great War writers. His men can be uncouth, foul-mouthed, brutalised by their social background, yet given to moments of great compassion and charity.

his 1948 best seller echoes Alexander Baron’s own military career as it follows a battalion of a fictional infantry brigade as they prepare for – and then take part in – D Day in the summer of 1944. The Fifth Wessex is, as the book’s title suggests, made up of a mixture of clumsy red-cheeked farm boys from the chalk uplands, well-read introverts who keep themselves to themselves, streetwise chancers and bewildered lads who are virgins in both bedroom and battlefield. They could be soldiers from earlier wars, and their ancestors might have known Agincourt, Marston Moor, Malplaquet, Talavera, Spion Kop and Arras. Baron has no time for the thinly veiled homo-eroticism of some of the Great War writers. His men can be uncouth, foul-mouthed, brutalised by their social background, yet given to moments of great compassion and charity. The British officer class have been long the object of scorn in both poetry and prose, but Baron deals with them in a largely sympathetic way. Those leading the Fifth on the ground are decent fellows; people who are only too aware of the frequently uneven struggle between shards of steel and the breasts of brave men. Even the Brigadier, whose plans prove so costly, is well aware of what he asks. He is, however, resolute in the way he shuts down his personal qualms in order to maintain the integrity of the battle plan. The one exception is the odious Major Maddison, a cold and sexually troubled narcissist whose demise is as satisfying as it is inevitable.

The British officer class have been long the object of scorn in both poetry and prose, but Baron deals with them in a largely sympathetic way. Those leading the Fifth on the ground are decent fellows; people who are only too aware of the frequently uneven struggle between shards of steel and the breasts of brave men. Even the Brigadier, whose plans prove so costly, is well aware of what he asks. He is, however, resolute in the way he shuts down his personal qualms in order to maintain the integrity of the battle plan. The one exception is the odious Major Maddison, a cold and sexually troubled narcissist whose demise is as satisfying as it is inevitable. aron writes lyrically about the midsummer grace of the French countryside, its orchards and abundance of wild flowers, some of which grace the helmets and tunics of the passing soldiers, their fragility which will contrast cruelly with the total vulnerability of the crumpled and shattered bodies of the men who wore them. For the driven and exhausted men of the Fifth Wessex, unlike their fathers before them, there is always a new unspoiled hillside, a grove of trees untouched by shellfire, a fresh sunken lane lined with roses and willow herb. For the war in Normandy is a war of movement. A field reeking with the blood of dead horses and cattle is soon left behind, as the Brigadier stabs his finger at the map and finds another bridge, another crossroads and another copse that must be taken.

aron writes lyrically about the midsummer grace of the French countryside, its orchards and abundance of wild flowers, some of which grace the helmets and tunics of the passing soldiers, their fragility which will contrast cruelly with the total vulnerability of the crumpled and shattered bodies of the men who wore them. For the driven and exhausted men of the Fifth Wessex, unlike their fathers before them, there is always a new unspoiled hillside, a grove of trees untouched by shellfire, a fresh sunken lane lined with roses and willow herb. For the war in Normandy is a war of movement. A field reeking with the blood of dead horses and cattle is soon left behind, as the Brigadier stabs his finger at the map and finds another bridge, another crossroads and another copse that must be taken. The heroes in From The City, From The Plough come in all shapes and sizes, but there are no winners. Let Alexander Baron (right) have the last word.

The heroes in From The City, From The Plough come in all shapes and sizes, but there are no winners. Let Alexander Baron (right) have the last word.

This is a vivid and moving account of preparations for D- Day and the advance into Normandy. Published in the 75th anniversary year of the D-Day landings, this is based on the author’s first-hand experience of D-Day and has been described by Antony Beevor as:

This is a vivid and moving account of preparations for D- Day and the advance into Normandy. Published in the 75th anniversary year of the D-Day landings, this is based on the author’s first-hand experience of D-Day and has been described by Antony Beevor as: This quietly shattering and searingly authentic depiction of the claustrophobia of jungle warfare in Malaya was described by William Boyd as:

This quietly shattering and searingly authentic depiction of the claustrophobia of jungle warfare in Malaya was described by William Boyd as: Anthony Quayle was a renowned Shakespearean actor, director and film star and this is his candid account of SOE operations in occupied Europe. Historian and journalist Andrew Roberts said:

Anthony Quayle was a renowned Shakespearean actor, director and film star and this is his candid account of SOE operations in occupied Europe. Historian and journalist Andrew Roberts said: This murder mystery about opportunism and the black market is set against the backdrop of London during the Blitz.

This murder mystery about opportunism and the black market is set against the backdrop of London during the Blitz.