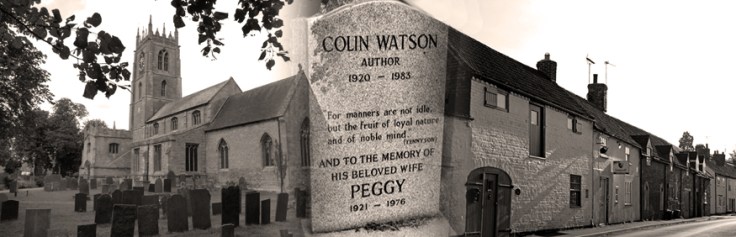

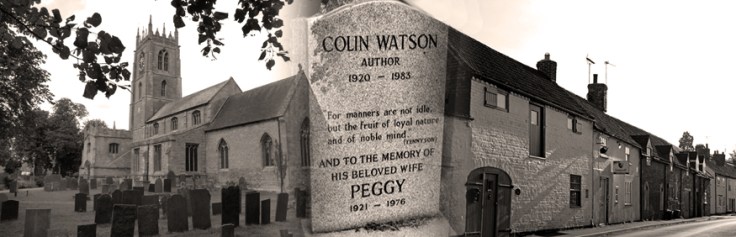

The introduction to this feature on Colin Watson,

including a biographical timeline, is here.

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked.

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked.

The permanent central character of Inspector Walter Purbright is beautifully named. ‘Purbright’ gives us a sense of sparky intelligence gleaming out from a solid, quintessentially English, impermeable foundation. He is described as a heavy man, with corn coloured hair. He has a deceptively reverential manner when dealing with the aldermen and worthies of Flaxborough, but he is no-one’s fool.

The sheer joy of this book in particular, and the Flaxborough novels in general, is the language. Perhaps it looks back rather than forward, but there are many modern writers who would happily pay homage to the unobtrusive Lincolnshire journalist. Of Mr Chubb, the Chief Constable, Watson observes:

“Not for the first time, he was visited with the suspicion that Chubb had donned the uniform of head of the Borough police force in a moment of municipal confusion when someone had overlooked the fact that he was really a candidate for the curatorship of the Fish Street Museum.”

Of the detecting skills of Sergeant Love, Purbright’s long-suffering subordinate, we learn:

“The sergeant was no adept of self effacing observation. When he wished to see without being seen, he adopted an air of nonchalance so extravagant that people followed him in expectation of his throwing handfuls of pound notes in the air.”

With such an ability to turn a phrase, it is almost irrelevant how the book pans out, but Watson does not let us down. Purbright uncovers a conspiracy involving loose women, a psychotic doctor and a distinctly underhand undertaker – hence the title. Watson himself remains mostly unknown to today’s reading public, but is rightly revered by connoisseurs of crime fiction. He was politically incorrect before the phrase was even invented and, although his pen pictures of self important provincial dignitaries are sharply perceptive, they also portray a fondness for the mundane and the ordinary lives lived beneath the layers of pretension.

There were to be be eleven more Flaxborough novels, and the final episode was Whatever’s Been Going On At Mumblesby? It again features Mr Bradlaw, the shamed undertaker from the very first novel. He has served his time for his part in those earlier misdeeds, however, and has returned to Flaxborough, thus giving the series a sense of things having come full circle. In 2011, Faber republished the series digitally, but the Kindle versions are not cheap and you might be better off seeking a secondhand paperback.

In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

He is particularly unimpressed by the efforts of writers such as H C McNeile (Sapper), Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward (Sax Rohmer) and E W Hornung. Whereas modern commentators might smile indulgently at the activities of Bulldog Drummond, Denis Nayland Smith and Arthur J Raffles, and view them as being ‘of their time’, Watson has none of it. He finds them racist bullies, insuperably snobbish and created purely to pander to the xenophobic and blinkered readership of what we would now call Middle England.

Watson’s apparent contempt for the Public School ethos prevalent in these writers of the first part of the twentieth century seems, at first glance, strange. He was educated at Whitgift School in Croydon, but in his day the school was a direct grant school, meaning that its charter stipulated that it provide scholarships for what its founder, Archbishop John Whitgift, termed,”poor, needy and impotent people” from the parishes of Croydon and Lambeth. The school has been fully independent for many years, but in Watson’s time there may have been an uneasy mix of scholarship boys and those whose wealthy parents paid full fees. Despite Watson and other local lads having gained their places by virtue of their brains, it is quite possible that they were looked down on by the ‘toffs’ who were there courtesy of their parents’ wealth.

As Watson trawls the deep for crime writers, even Dorothy L Sayers doesn’t escape his censure, as he is irritated by Lord Peter Wimsey’s foppishness and tendency to make snide remarks at the expense of the lower classes. Edgar Wallace and E Phillips Oppenheim who, between them, sold millions of novels, are dismissed as mere hacks, but he does show begrudging admiration for the works of the woman he calls ‘Mrs Christie’, despite rubbishing her archetypal English village crime scene, which he scorns as Mayhem Parva. Watson admires Conan Doyle’s clever product placement, Margery Allingham’s inventiveness and ends the book with a reasonably affectionate study of James Bond, although he is less than sanguine about 007’s prowess as a womaniser:

‘The sexual encounters in the Bond books are as regular and predictable as bouts of fisticuffs in the ‘Saint’ adventures or end-of-chapter red herrings in the detective novels of Gladys Mitchell, and not much more erotic.”

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote

“Gaunt, sharp-featured, a little wary of the stranger on the step, Watson interrupted his work as a silversmith. Eyeglass. Tools in hand. He couldn’t understand where it had all gone wrong. His novels were well-received and they’d even had a few moments of television time, with Anton Rodgers as the detective. The problem was that Watson, lèse-majesté , had trashed Agatha Christie in an essay called ‘The Little World of Mayhem Parva’.

Watson put away his instruments, took me upstairs to the living room. He signed my books, we parted. He was astonished that all his early first editions were a desirable commodity while his current publications, the boxes of Book Club editions, filled his shelves. He would have to let the writing game go, it didn’t pay. Concentrate on silver rings and decorative trinkets.” (Iain Sinclair “Edge of the Orison” Hamish Hamilton 2005.)

The dust jackets of the Bryant & May novels are a work of art in themselves, but between the covers is where the true genius lies. Arthur Bryant and John May are detectives working for the Peculiar Crimes Unit, an imaginary department of London’s Metropolitan Police. Their adventures take them mostly to curious and forgotten corners of London where the past is just below the modern surface. Fowler has many talents as a writer, not least of which is his comedic talent. He is a direct descendant of English humourists such as George and Weedon Grossmith and HV Morton, and the jokes come thick and fast amid the serious business of solving murders or strange crimes.

The dust jackets of the Bryant & May novels are a work of art in themselves, but between the covers is where the true genius lies. Arthur Bryant and John May are detectives working for the Peculiar Crimes Unit, an imaginary department of London’s Metropolitan Police. Their adventures take them mostly to curious and forgotten corners of London where the past is just below the modern surface. Fowler has many talents as a writer, not least of which is his comedic talent. He is a direct descendant of English humourists such as George and Weedon Grossmith and HV Morton, and the jokes come thick and fast amid the serious business of solving murders or strange crimes.

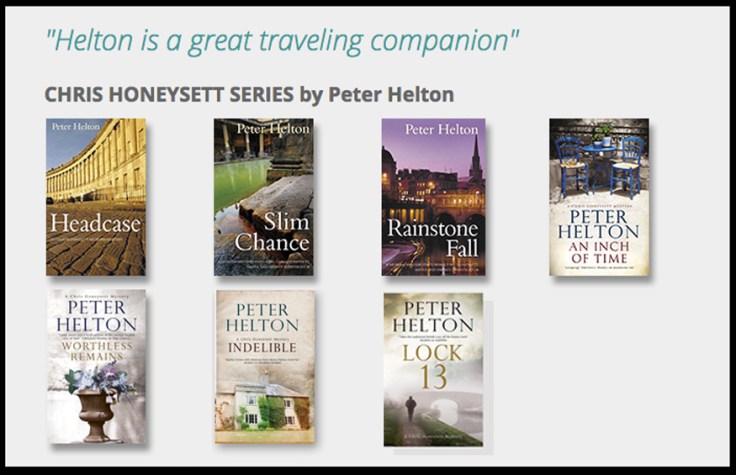

Lock 13 features Chris Honeysett, a private detective whose cases I had never read before, despite this being the sixth in what is clearly a popular series. The previous episodes are Headcase (2005), Slim Chance (2006) Rainstone Fall (2008) An Inch of Time (2012) Worthless Remains (2013) and Indelible (2014). Honeysett, like his creator Peter Helton (more on Helton’s website

Lock 13 features Chris Honeysett, a private detective whose cases I had never read before, despite this being the sixth in what is clearly a popular series. The previous episodes are Headcase (2005), Slim Chance (2006) Rainstone Fall (2008) An Inch of Time (2012) Worthless Remains (2013) and Indelible (2014). Honeysett, like his creator Peter Helton (more on Helton’s website  Sometimes a novel is so delightfully written that a reader can reach the last page with a smile and sense of contentment, despite the fact that nothing very dramatic or shocking, at least by the standards of some modern thrillers, has happened during the 200 pages or so which have made up the narrative. Lock 13 is one such book. Peter Helton (right) tells the story through the eyes of Chris Honeysett, and the style is fluent, conversational, occasionally erudite, often witty – but always very, very, readable. Established fans of the Honeysett series can feel duly smug that the amiable painter-sleuth has found another convert, and they can rest assured that I shall be working my way through the file of Honeysett’s previous cases. Lock 13 is published by

Sometimes a novel is so delightfully written that a reader can reach the last page with a smile and sense of contentment, despite the fact that nothing very dramatic or shocking, at least by the standards of some modern thrillers, has happened during the 200 pages or so which have made up the narrative. Lock 13 is one such book. Peter Helton (right) tells the story through the eyes of Chris Honeysett, and the style is fluent, conversational, occasionally erudite, often witty – but always very, very, readable. Established fans of the Honeysett series can feel duly smug that the amiable painter-sleuth has found another convert, and they can rest assured that I shall be working my way through the file of Honeysett’s previous cases. Lock 13 is published by

The Island is the latest episode in the eventful partnership between two gentleman detectives in Victorian London. James Batchelor is a former journalist, a ‘gentleman’ in manners and intelligence, if not by upbringing, while his colleague Matthew Grand is an American former soldier, and scion of a very wealthy patrician New Hampshire family. We first met them in

The Island is the latest episode in the eventful partnership between two gentleman detectives in Victorian London. James Batchelor is a former journalist, a ‘gentleman’ in manners and intelligence, if not by upbringing, while his colleague Matthew Grand is an American former soldier, and scion of a very wealthy patrician New Hampshire family. We first met them in  A few words in praise of the author. Meiron Trow (right) is one of the most erudite and entertaining writers in the land. Over thirty years ago he began his tongue in cheek series rehabilitating the much-put-upon Inspector Lestrade, and I loved every word. I then became hooked on his Maxwell series, featuring a very astute crime-solving history teacher who, while eschewing most things modern, manages to be hugely respected by the sixth-formers (Year 12 and 13 students in new money) in his charge, while managing to terrify and alarm the younger ‘teaching professionals’ who run his school. I was well into the Maxwell series before I realised that MJ Trow and I had two things (at least) in common. Firstly, he went to the same school as I did, although I have to confess he was a couple of years ‘below’ me and would have been dismissed at the time as a pesky ‘newbug’. Secondly, and much more relevant to my love of his Maxwell books, I discovered that we were both senior teachers in state secondary schools, and shared a disgust and contempt for the tick-box mentality characterising the so-called ‘leadership’ of high schools.

A few words in praise of the author. Meiron Trow (right) is one of the most erudite and entertaining writers in the land. Over thirty years ago he began his tongue in cheek series rehabilitating the much-put-upon Inspector Lestrade, and I loved every word. I then became hooked on his Maxwell series, featuring a very astute crime-solving history teacher who, while eschewing most things modern, manages to be hugely respected by the sixth-formers (Year 12 and 13 students in new money) in his charge, while managing to terrify and alarm the younger ‘teaching professionals’ who run his school. I was well into the Maxwell series before I realised that MJ Trow and I had two things (at least) in common. Firstly, he went to the same school as I did, although I have to confess he was a couple of years ‘below’ me and would have been dismissed at the time as a pesky ‘newbug’. Secondly, and much more relevant to my love of his Maxwell books, I discovered that we were both senior teachers in state secondary schools, and shared a disgust and contempt for the tick-box mentality characterising the so-called ‘leadership’ of high schools. I digress, so back to New Hampshire in the early spring of 1873. The guests begin to arrive, and the ‘downstairs’ staff under the stern eye of the enigmatic butler, Waldo Hart, are emulating the proverbial blue-arsed fly. Trow, at this point, gleefully takes the template of the traditional country house mystery, and has his evil way with it. Despite the title of the book, we are not quite in Soldier Island (And Then There Were None) territory, but Rye is far enough from Boston to make sure that when the first murder happens, the real policemen are too far away and too engrossed with their city crime to pay much attention, even when when of the possible suspects is a certain Mr Samuel Langhorne Clemens. (left)

I digress, so back to New Hampshire in the early spring of 1873. The guests begin to arrive, and the ‘downstairs’ staff under the stern eye of the enigmatic butler, Waldo Hart, are emulating the proverbial blue-arsed fly. Trow, at this point, gleefully takes the template of the traditional country house mystery, and has his evil way with it. Despite the title of the book, we are not quite in Soldier Island (And Then There Were None) territory, but Rye is far enough from Boston to make sure that when the first murder happens, the real policemen are too far away and too engrossed with their city crime to pay much attention, even when when of the possible suspects is a certain Mr Samuel Langhorne Clemens. (left)

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked.

Coffin Scarcely Used – the first of The Flaxborough Chronicles – begins with the owner of the local newspaper dead in his carpet slippers, beneath an electricity pylon, on a winter’s night. Throw into the mix an over-sexed undertaker, a credulous housekeeper, the strangely shaped burns on the hands of the deceased, a chief constable who cannot believe that any of his golf chums could be up to no good, and a coffin containing only ballast, and we have a mystery which might be a Golden Age classic, were it not for the fact that Watson was, at heart, a satirist, and a writer who left no balloon of self importance unpricked. In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

In addition to such delightful titles as Broomsticks Over Flaxborough and Six Nuns And A Shotgun (in which Flaxborough is visited by a New York hitman) Watson also wrote an account of the English crime novel in its social context. In Snobbery With Violence (1971), he sought to explore the attitudes that are reflected in the detective story and the thriller. Readers expecting to find Watson reflecting warmly on his contemporaries and predecessors will be disappointed. The general tone of the book is almost universally waspish and, on some occasions, downright scathing.

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote

In the end, it seems that Watson had supped full of crime fiction writing. Iain Sinclair sought him out in his later years at Folkingham, and wrote

Other murders follow, and each has been committed in one of the parks and gardens – the Wild Chambers – which are scattered throughout central London. Are the gardens linked, like some erratically plotted ley line? Why are the murders connected to a tragic freak accident in a road tunnel near London Bridge? Why are the murder sites speckled with tiny balls of lead?

Other murders follow, and each has been committed in one of the parks and gardens – the Wild Chambers – which are scattered throughout central London. Are the gardens linked, like some erratically plotted ley line? Why are the murders connected to a tragic freak accident in a road tunnel near London Bridge? Why are the murder sites speckled with tiny balls of lead? Along the way, Fowler (right) has the eagle eye of John Betjeman in the way that he recognises the potency of ostensibly insignificant brand names and the way that they can instantly recreate a period of history, or a passing social mood. At one point, Bryant tries to pay for a round of drinks in a pub:

Along the way, Fowler (right) has the eagle eye of John Betjeman in the way that he recognises the potency of ostensibly insignificant brand names and the way that they can instantly recreate a period of history, or a passing social mood. At one point, Bryant tries to pay for a round of drinks in a pub: