![]()

Crime fiction and comedy can sometimes make strange bedfellows, but in the right hands it can be beguiling. Back in time, The Big Bow Mystery by Israel Zangwill shared the same kind of subtle social comedy employed by George and Weedon Grossmith, while the Bryant and May novels by the late Christopher Fowler were full of excellent gags. So, how does One Man Down by Alex Pearl measure up?

For starters, this has to be tagged as historical crime fiction, as it is set in a 1984 London, in the strange (to me) world of advertising copywriters and their attempts to secure contracts to sell various products. It may only be forty years ago, but we are in the world of Filofaxes, Psion personal organisers and IBM golfball typewriters. The main thread of the plot involves two lads who are connoisseurs of the catch phrase and sorcerers of the strap-line. Brian and Angus become involved in a complex affair which includes a depressive photographer who is arrested for exposing himself to an elderly former GP on the seafront at Margate, and the attempt to blackmail a gay vicar. Incidentally, the Margate reference is interesting because in recent times the seaside town has been somewhat rehabilitated thanks to the patronage of Tracey Emin, but at the time when the book is set, it was certainly a very seedy place. Along with other decaying resorts like Deal, this part of the Kent coast was prominently featured in David Seabrook’s All The Devils Are Here.

When Brian and Angus find the photographer – Ben Bartlett – involved in blackmailing the vicar, dead in his studio, things take a macabre turn. This thread runs parallel to events that have a distinctly Evelyn Waugh flavour. The two ad-men are speculating about just how dire some of the industry’s efforts are, and Angus takes just four and a half minutes to dash off a spoof commercial for a chocolate bar campaign they know the agency has been booked to handle. Angus makes it as dreadful as he can. The pair go out for a drink, leaving the parody on the desk, forgetting they were due to meet one of the firm’s top men to talk about the real campaign. Annoyed to find them absent, the manager finds the sheet of A4, thinks it wonderful, and promptly takes it to the Cadbury top brass, who share his enthusiasm.

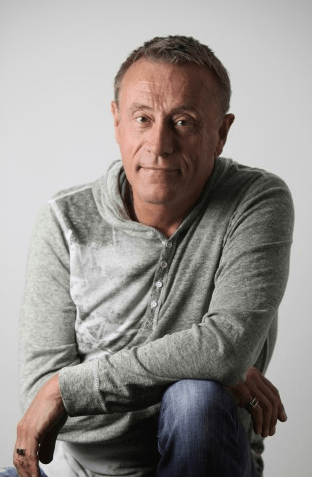

Alex Pearl (left) isn’t a reluctant name-dropper, and walk on parts for Julian Clary and Kenneth Clarke (in Ronnie Scott’s, naturally) set the period tone nicely. 1984 was certainly a memorable year. I remember driving through the August night to be at my dying dad’s bedside, and hearing on the radio that Richard Burton had died. Just a few weeks earlier we had been blown away by Farrokh Bulsara at Wembley, while Clive Lloyd and his men were doing something rather similar to the English cricket team.

Alex Pearl (left) isn’t a reluctant name-dropper, and walk on parts for Julian Clary and Kenneth Clarke (in Ronnie Scott’s, naturally) set the period tone nicely. 1984 was certainly a memorable year. I remember driving through the August night to be at my dying dad’s bedside, and hearing on the radio that Richard Burton had died. Just a few weeks earlier we had been blown away by Farrokh Bulsara at Wembley, while Clive Lloyd and his men were doing something rather similar to the English cricket team.

Back to One Man Down. All’s well that ends well, and we have another murder, but one that saves the career and reputation of the blackmailed vicar. This is not a long book – just 183 pages – but I thoroughly enjoyed it. I am a sucker for anything that mentions cricket, and here the story more or less begins and ends on the cricket pitch. The solution to the murder(s) is elegant and subtle. The book is published by Roundfire Books and is available now.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

We are in Sicily, and it is the long hot summer of 1966. Brighton crime reporter Colin Crampton has taken his Aussie girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith abroad for a holiday. While the sun beats down, and gentle breezes blow in from the Mediterranean, Colin hopes to choose a romantic location – perhaps the ruin of a Greek temple – where he will go down on one knee and propose marriage to the beautiful Shirl. He has an expensive diamond ring in his pocket to help boost his case, but it is not to be.

We are in Sicily, and it is the long hot summer of 1966. Brighton crime reporter Colin Crampton has taken his Aussie girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith abroad for a holiday. While the sun beats down, and gentle breezes blow in from the Mediterranean, Colin hopes to choose a romantic location – perhaps the ruin of a Greek temple – where he will go down on one knee and propose marriage to the beautiful Shirl. He has an expensive diamond ring in his pocket to help boost his case, but it is not to be.

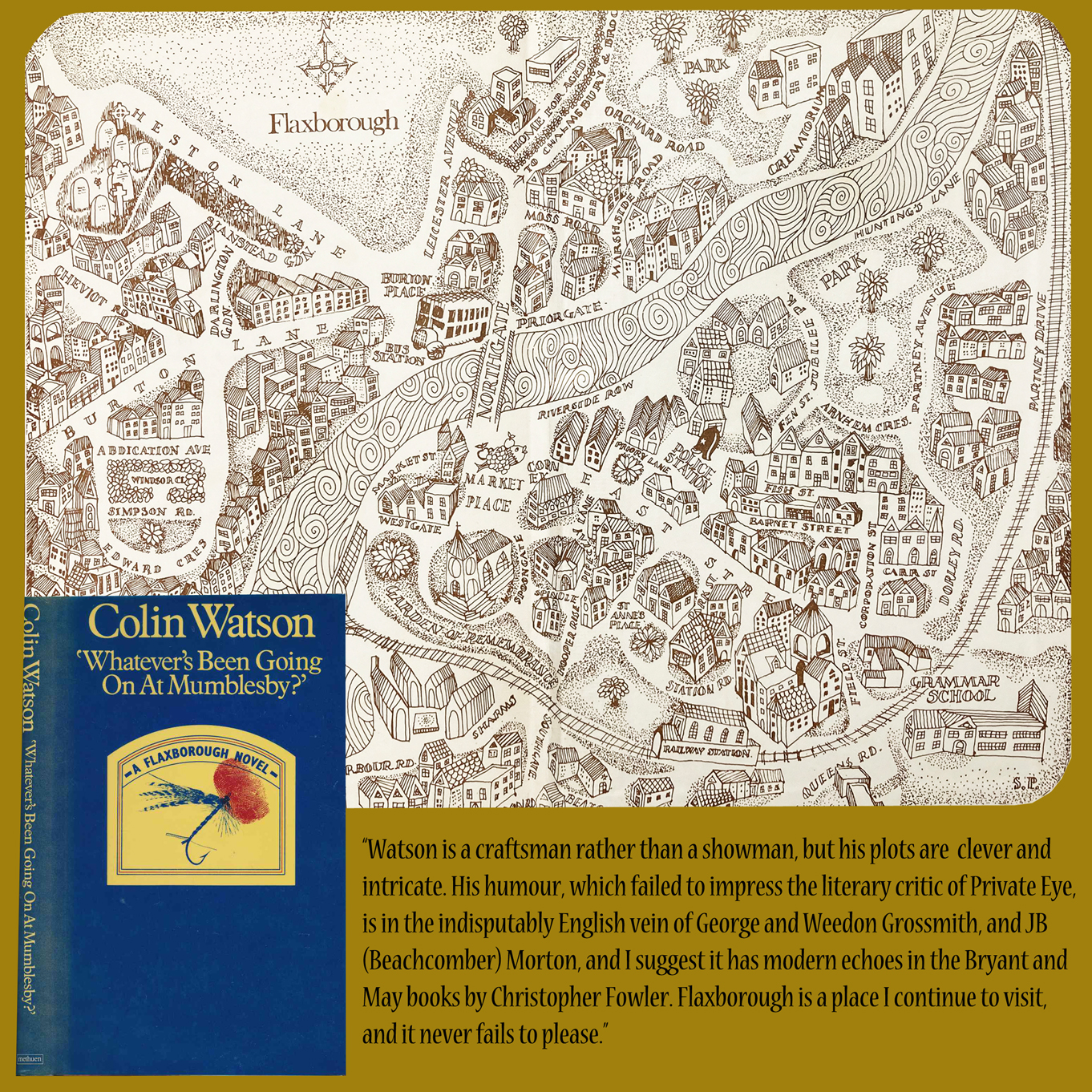

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

The true provenance of this is only revealed when Purbright investigates an apparent suicide which happened in the village church. Bernadette Croll, the wife of a local farmer was, in life, “no better than she ought to be”, and in death little mourned by the several men who shared her charms. Purbright eventually sees the connection between Mrs Croll’s death and Mr Loughbury’s collection of valuables, when he discovers that the wood came from somewhere far less exotic than Golgotha.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle. One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master.

One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master. hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her.

hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her. ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly.

ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly. Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

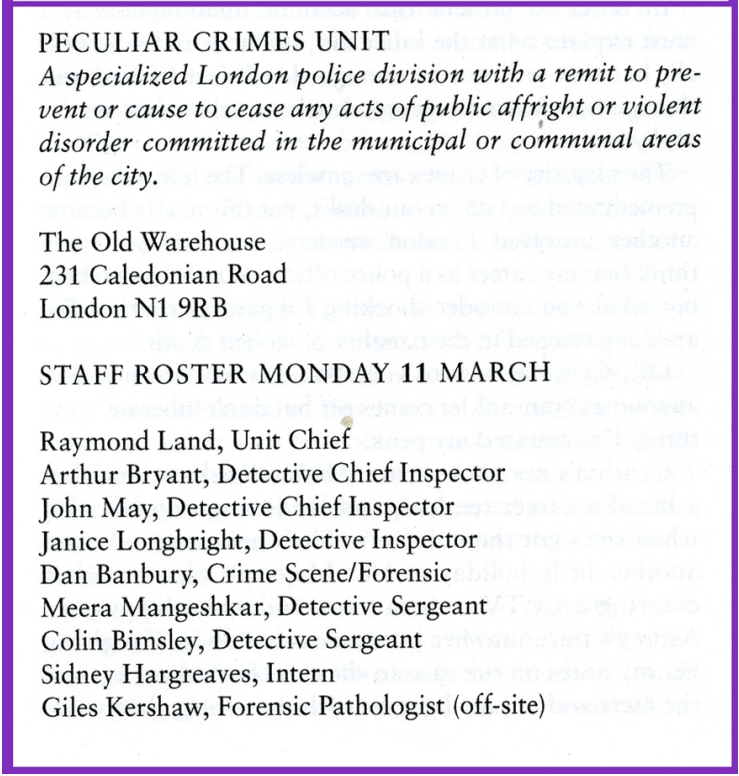

or newcomers to the sublime world of Arthur Bryant and John May, the new collection of short stories written by their biographer, Christopher Fowler, contains a handy pull-out-and-keep guide to the personnel doings of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit. OK, I lie – don’t try and pull it out because it will wreck a beautiful book, but the other bits are true.

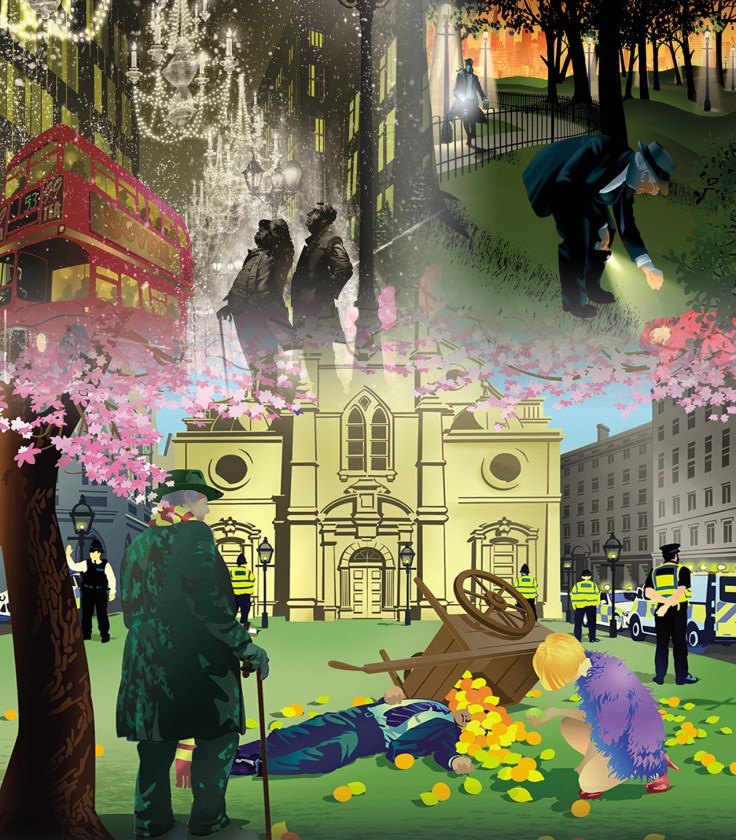

or newcomers to the sublime world of Arthur Bryant and John May, the new collection of short stories written by their biographer, Christopher Fowler, contains a handy pull-out-and-keep guide to the personnel doings of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit. OK, I lie – don’t try and pull it out because it will wreck a beautiful book, but the other bits are true. Leaving aside the pen pictures, introductions and postscripts, there are twelve stories. They are, for the most part, enjoyably formulaic in a Sherlockian way in that something inexplicable happens, May furrows his brow and Arthur comes up with a dazzling solution. Think of a dozen elegant variations of The Red Headed League, but with one or two being much darker in tone. Bryant & May and the Antichrist, for example, is a sombre tale of an elderly woman driven to suicide by the greed of a religious charlatan, while Bryant & May and the Invisible Woman reflects on the devastating effects of clinical depression. The stories are, of course set in London, apart from the delightfully improbable one where Arthur and John solve a murder within the blood-soaked walls of Bran Castle, once the des-res of Vlad Dracul III. Bryant & May and the Consul’s Son revisits Fowler’s fascination with the lost rivers of London, while Janice Longbright and the Best of Friends lets the redoubtable Ms L take centre stage.

Leaving aside the pen pictures, introductions and postscripts, there are twelve stories. They are, for the most part, enjoyably formulaic in a Sherlockian way in that something inexplicable happens, May furrows his brow and Arthur comes up with a dazzling solution. Think of a dozen elegant variations of The Red Headed League, but with one or two being much darker in tone. Bryant & May and the Antichrist, for example, is a sombre tale of an elderly woman driven to suicide by the greed of a religious charlatan, while Bryant & May and the Invisible Woman reflects on the devastating effects of clinical depression. The stories are, of course set in London, apart from the delightfully improbable one where Arthur and John solve a murder within the blood-soaked walls of Bran Castle, once the des-res of Vlad Dracul III. Bryant & May and the Consul’s Son revisits Fowler’s fascination with the lost rivers of London, while Janice Longbright and the Best of Friends lets the redoubtable Ms L take centre stage. he gags are as good as ever. While investigating a crime in a tattoo parlour, Arthur is mistaken for a customer and asked if he has a design in mind:

he gags are as good as ever. While investigating a crime in a tattoo parlour, Arthur is mistaken for a customer and asked if he has a design in mind: