The new Aector McAvoy novel by David Mark begins with a bloodbath. A man is being literally ripped to pieces with the savagery torturers used to flay saints in medieval times. Just as it seems the victim is done for, someone comes to his rescue, in the shape of a small but fierce woman. We soon learn that the tortured man is Decland Parfitt who would, after he made an almost miraculous recovery, be jailed for child sexual abuse. His rescuer? Aector McAvoy’s long time boss, the formidable Chief Detective Superintendent Trish Pharaoh.

The story actually begins with a man driving in the pouring rain along a remote minor road in East Yorkshire. The driver, a man named Joe, is getting an ear-bashing from his ex-wife – who is on speaker phone – over the way he has let their daughter down. Distracted by her tirade and with the windscreen misting up, he feels a large bang, and knows he has hit something. When he gets out of the car he sees what appears to be a large black bag lying in the road. Rapidly calculating that there will be no cameras nearby, he gets back in the car and drives off. The bag is later found to contain a body – that of John Dennic, jailed for a savage assault on a police officer, and an acquaintance of Parfitt in prison. Dennic had been on day release when he went missing.

Parfitt was an arch-deceiver. He brought fun and laughter to countless youngsters across the region as a children’s entertainer. Dressed rather like Lofty in It Ain’t Half Hot Mum, he was everyone’s favourite uncle, with his jokes, his performing animals and his sunny disposition. He was a single man, but that rang no alarm bells with the local authorities when he applied to be a foster parent to two damaged sisters. Incredibly, his request was granted. One of the girls, Gaynor, suffered such abuse at his hands, that she later committed suicide. Younger sister Ruby, however, adored her foster dad and swore on oath that Gaynor was in a state of drug induced delusion.

Trish Pharaoh has two major problems to deal with and, by definition, they become McAvoy’s too. It seems that the prison authorities are determined to release Parfitt from prison, and Pharaoh needs to stop this. Second, she needs to disturb Ruby’s deep conviction that her foster father is a decent man who was wrongly convicted. Pharaoh is also convinced that Parfitt was also responsible for the abduction and murder of at least two girls, whose bodies have never been found.

The cast of villains in many of David Mark’s novels resemble the creations of the great Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch. Bosch was obsessed with the darker side of humanity, and if you take a magnifying glass to his paintings, you can see tormented individuals, scurrying this way and that in the hellish landscape in which the painter has placed them. Bosch painted a figurative mouth of Hell, a gaping maw into which humans are sucked. Mark’s villains, such as Parfitt and Dennic are consumed by a metaphorical hell created from their own misdeeds. This is dark stuff, and not for the cosy crime community. Past Redemption is, however a fierce and gripping tale of evil deeds committed against the grey and dreary background of a city once vibrant with the noise and smells of its fishing industry, but now reduced to a backwater trying to celebrate what it once was.

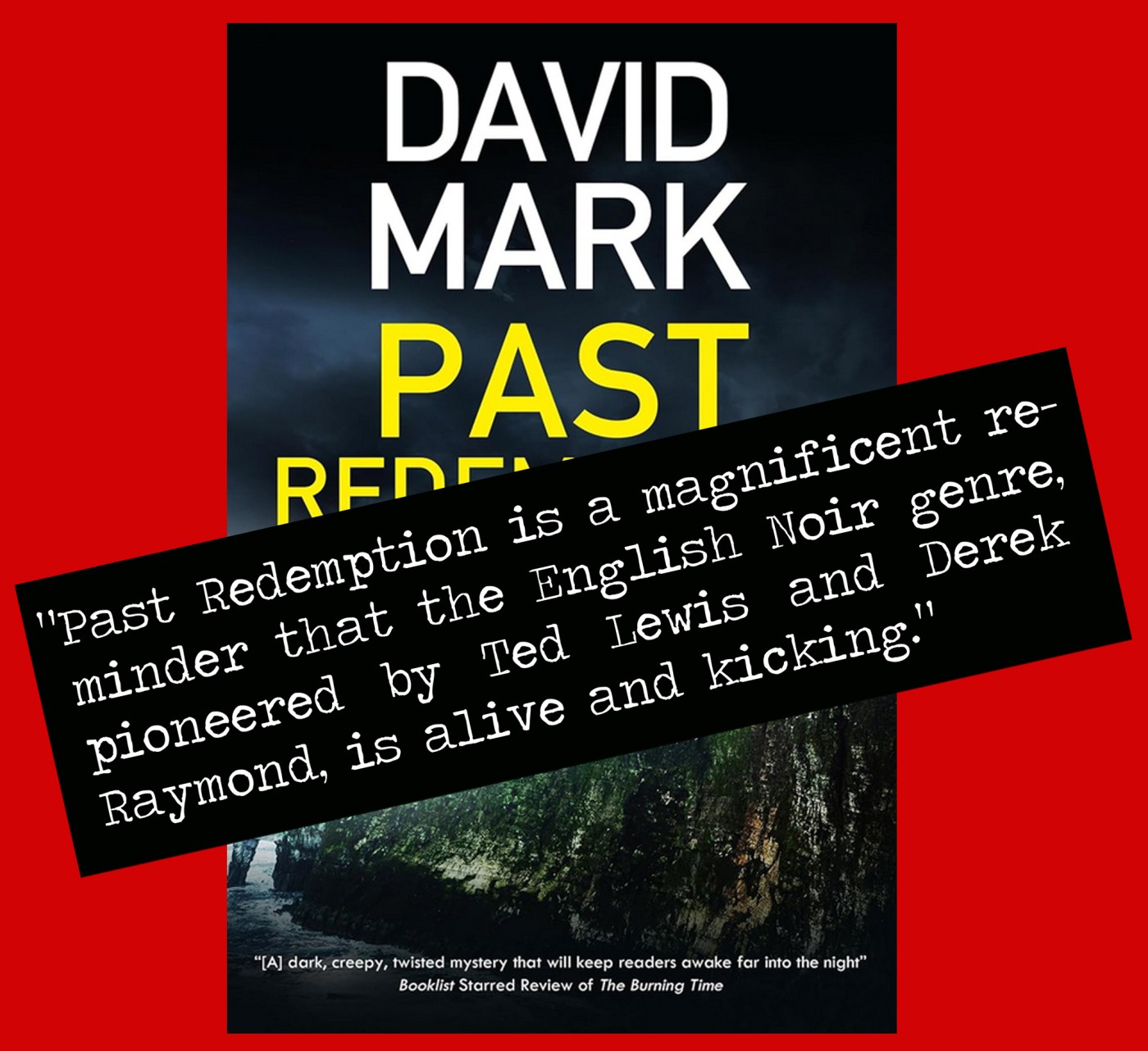

The novel plays out with dramatic revelations of people who have pretended to be one thing, but were something else entirely. It is no coincidence that the man who nearly killed Parfitt, and may have killed Dennic has the nickname Virgil. David Mark himself plays Dante’s Virgil, as he leads us through Purgatory and Hell, contrasting his monstrous villains with McAvoy who, although, a physical giant, is gentle, endearingly clumsy, but fiercely brave. Past Redemption is a magnificent reminder that the English Noir genre, pioneered by Ted Lewis and Derek Raymond, is alive and kicking. The novel is published by Severn House and will be available on 3rd December.

The book begins with a flashback to an attempt by young men to carry out what seems to be a robbery in an isolated rural property. It ends in horrific violence, matched only by the destructive storm that rages over the heads of the ill-advised and ill-prepared group. Cut to the present day, and another storm has lashed Humberside, bringing down power lines, flooding homes, and uprooting trees. One such tree, an ancient ash, reveals something truly awful – a human body, mostly decayed, entwined within its roots in a macabre embrace.

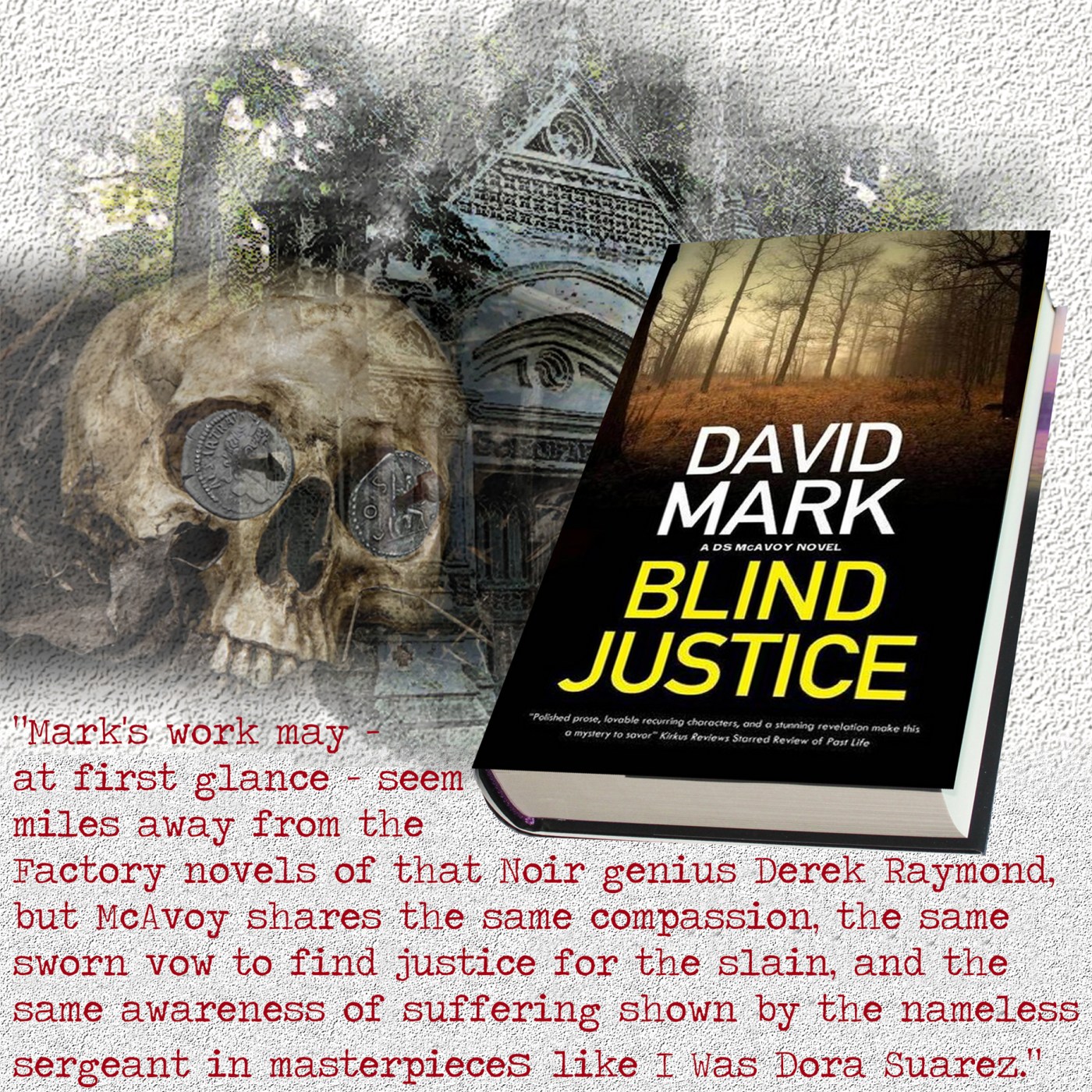

The book begins with a flashback to an attempt by young men to carry out what seems to be a robbery in an isolated rural property. It ends in horrific violence, matched only by the destructive storm that rages over the heads of the ill-advised and ill-prepared group. Cut to the present day, and another storm has lashed Humberside, bringing down power lines, flooding homes, and uprooting trees. One such tree, an ancient ash, reveals something truly awful – a human body, mostly decayed, entwined within its roots in a macabre embrace. David Mark (right) writes with a sometimes frightening intensity as dark events swirl around Aector McAvoy. The big man, gentle and hesitant though he may seem, is, however, like a rock. He is one of the most original creations in a very crowded field of fictional British coppers, and his capacity to bear pain for others – particularly in this episode his son Fin and Trish Pharoah – is movingly described. Mark’s work may – at first glance – seem miles away from the Factory novels of that Noir genius Derek Raymond, but McAvoy shares the same compassion, the same sworn vow to find justice for the slain, and the same awareness of suffering shown by the nameless sergeant in masterpieces like I Was Dora Suarez.

David Mark (right) writes with a sometimes frightening intensity as dark events swirl around Aector McAvoy. The big man, gentle and hesitant though he may seem, is, however, like a rock. He is one of the most original creations in a very crowded field of fictional British coppers, and his capacity to bear pain for others – particularly in this episode his son Fin and Trish Pharoah – is movingly described. Mark’s work may – at first glance – seem miles away from the Factory novels of that Noir genius Derek Raymond, but McAvoy shares the same compassion, the same sworn vow to find justice for the slain, and the same awareness of suffering shown by the nameless sergeant in masterpieces like I Was Dora Suarez.

The story begins with a murder, graphically described and, at this point in the review, it is probably pertinent to warn squeamish readers to return to the world of painless and tidy murders in Cotswold manor houses and drawing rooms, because death in this book is ugly, ragged, slow and visceral. The victim is a middle-aged woman who makes a living out of reading Tarot cards, tea leaves, crystal balls and other trinkets of the clairvoyance trade. She lives in an isolated cottage on the bleak shore of the Humber and, one evening, with a cold wind scouring in off the river, she tells one fortune too many.

The story begins with a murder, graphically described and, at this point in the review, it is probably pertinent to warn squeamish readers to return to the world of painless and tidy murders in Cotswold manor houses and drawing rooms, because death in this book is ugly, ragged, slow and visceral. The victim is a middle-aged woman who makes a living out of reading Tarot cards, tea leaves, crystal balls and other trinkets of the clairvoyance trade. She lives in an isolated cottage on the bleak shore of the Humber and, one evening, with a cold wind scouring in off the river, she tells one fortune too many. “She has found herself some mornings with little horseshoe grooves dug into the soft flesh of her palms. Sometimes her wrists and elbows ache until lunchtime. She sleeps like a toppled pugilist: a Pompeian tragedy. She sees such terrible things in the few snatched moments of unconsciousness.”

“She has found herself some mornings with little horseshoe grooves dug into the soft flesh of her palms. Sometimes her wrists and elbows ache until lunchtime. She sleeps like a toppled pugilist: a Pompeian tragedy. She sees such terrible things in the few snatched moments of unconsciousness.”