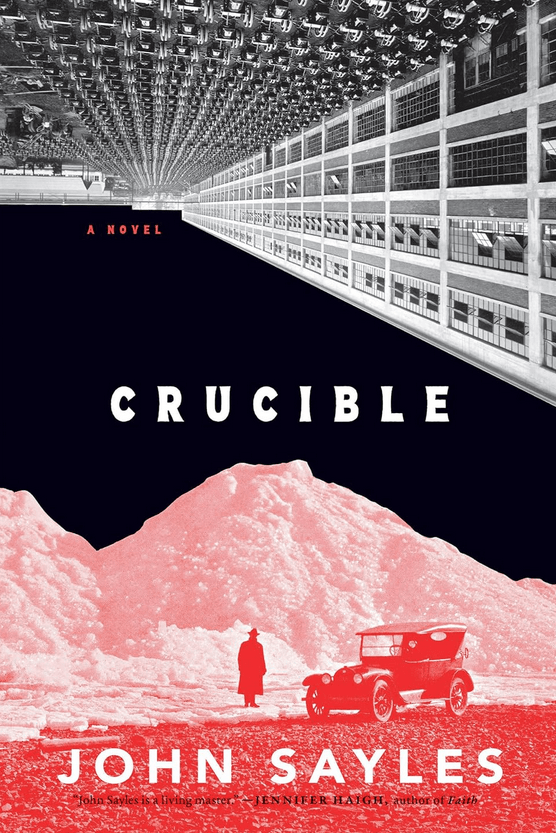

John Sayles sets out with a huge canvas to fill, and it is the fortunes of the Ford motor company from the end of the Great War to the uncertain times of a post-war world where both Hitler and Hirohito have been humbled, but Stalin remains the one world leader with unassailable power.

The key points of the early pages are the stock market crash of 1929 and Henry Ford’s bizarre attempt to buy up swathes of Amazonian rain forest to produce his own rubber. The Americans sent out there are overwhelmed by a number of factors, including the human problems that hundreds of indigenous peasants are unable to adapt to Henry Ford’s production line work ethic, and the purely botanical fact that rubber trees are not a quickly growing commodity yielding instant rewards. Ford has despatched his minions to the Brazilian jungle to produce cheap rubber. He has no concept of the place. This is not a treasure trove of natural wonder described in a whispered David Attenborough voice-over. It is – for the Americans – a hell slithering with giant ants, poisonous spiders, caimans that will rip the arm off an unwary dabbler, ferocious heat, endless rain, decay, and the sense that humans are, at best, merely clinging on to life by their fingernails.

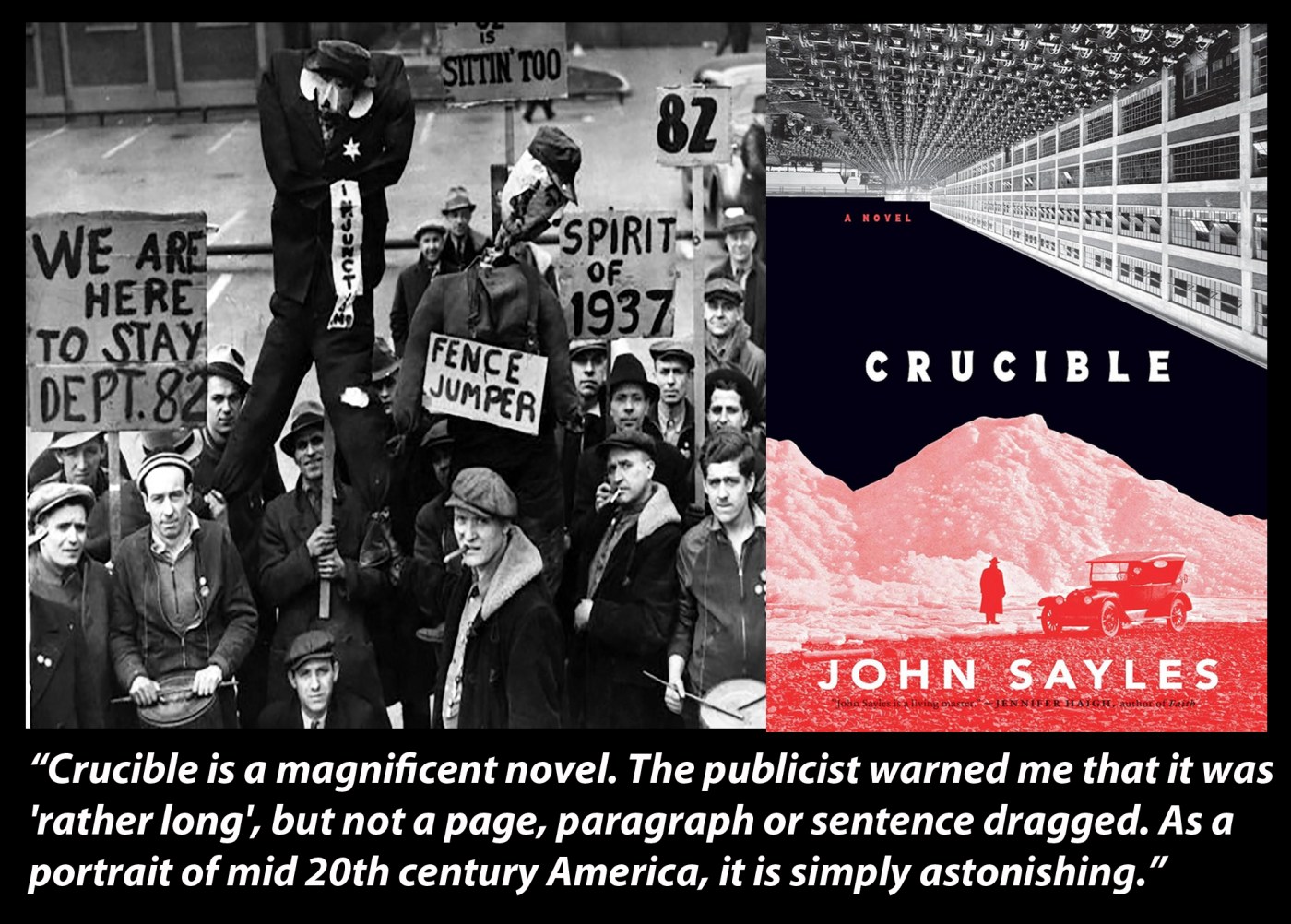

John Sayles has painted a picture of Henry Ford, warts and all, which both appalls and captivates.Does Sayles take sides? Yes, of course he does, given his CV, but his partiality does not diminish the power of his prose. There is a deep irony, however, when we read of the funeral procession for the left wing activists killed in an anti Ford protest march. Simultaneously, thousands of miles away, Stalin was systematically starving millions of Ukrainians with one hand, while butchering political opponents with the other, all in the name of the Great Socialist Ideal which the idealistic American marches seem to be calling for. Sayles’ narrative points up this and many other many ironies and moral dilemmas for historians. The chief example, for me, was that of the human brutality of the industrial process which, for us Brits, began in the remorseless cotton mills and iron foundries centuries ago.

Here, in 1930s Detroit, the assembly line is unrelenting and unforgiving: a momentary lapse of concentration can destroy a man’s leg, his hands, or his sight. There was no such thing as Health and Safety in the middle years of the 20th century. And yet, and yet. Were things any better in Stalin’s Soviet Union? Were his political commissars and better than Harry Bennett’s thugs? The novel will be on the shelves labeled ‘fiction’, but is peopled by real life characters almost too outrageous to have been invented by a mere author. We have Ford himself, a strange mix of psychopath and philanthropist; Harry Bennett, his unscrupulous enforcer who would have been at home working for Reynhardt Heydrich; Jerry Buckley, the charismatic radio host assassinated in 1930.

Crucible is a reminder that, amidst all the formulaic production line American fiction that sells by the million on supermarket shelves, there are still good writers out there.’sprawling’and ‘epic’ were adjectives once used to describe novels or films with huge breadth and compass. In this sense, Crucible certainly ‘sprawls, but along the way Sayles pens a kind of love letter to the racial and cultural blend of ordinary people who were striving to become Americans by taking Henry Ford’s dollar, the Sicilians, the dirt-poor Blacks forced to emigrate north, the ex-European Jews, the resilient Poles, the flint-hard Scots and their Irish cousins. In his afterword, however Sayles eschews sentimentality, particularly in view of the savage Detroit race riots of 1943:

“..enormous social and economic forces rushed together in that city, making it more a high-pressure crucible than a genteel American melting pot.”

For all that Henry Ford is not one of history’s most lovable characters, we should not forget his pragmatism. Criticised by many then and now for his apparent Nazi sympathies, we must not forget that it was his factories which produced the B24 Liberator bombers, the thousands of jeeps and Sherman tanks which helped bring about the fall of the Third Reich.

Crucible is a magnificent novel. The publicist warned me that it was ‘rather long’, but not a page, paragraph or sentence dragged. As a portrait of mid 20th century America, it is simply astonishing. Published by Melville House, it is available now.

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as

Widdershins, by the way is a strange word. Some say it was German, others say it originated in Scotland. It translates as