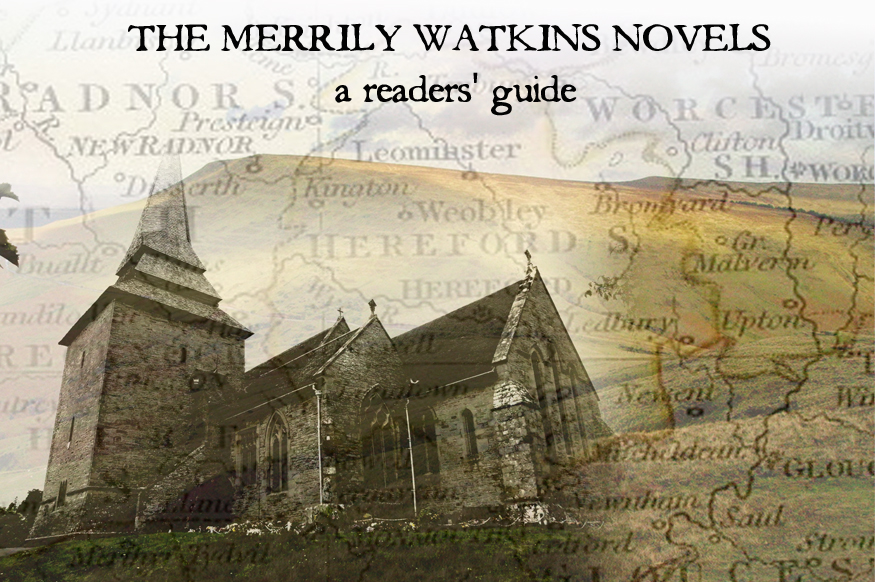

It seems like half a lifetime since there was a Merrily Watkins novel – it was All of a Winter’s Night back in 2017 (click the title to read my review) and there has been one hell of a lot of water under the bridge for all of us since then including, sadly, Phil Rickman suffering serious illness. His many fans will join me in hoping that he is on the mend, and at last we have a new book! Old Ledwardine hands won’t need reminding, but for newcomers this graphic may be helpful.

Now, as another celebrated solver of mysteries once said, “The game’s afoot!” We are in relatively modern times, March 2020, and the Covid Curse has begun to cast its awful spell. The senior Anglican clergy, including the Bishop of Hereford, are relentlessly determined to be woker than woke, and have decided that exorcism – or, to use the other term, deliverance – is the stuff or the middle ages, and clergy are being advised to refer any strange events to the NHS mental health teams. This, of course, puts Merrily Watkins’ ‘night job’ under threat. She and her mentor Huw Owen know that some people experience events which cannot simply be the result of their poor mental health.

The Merrily Watkins novels have a template. This is not to say they are formulaic in a derogatory sense. The template involves a crime – most often a murder or mysterious death. This is investigated by the West Mercia police, usually in the form of Inspector Frannie Bliss. The investigation then reveals what appear to be supernatural or paranormal characteristics, which then secures the involvement of the Rev. Merrily Watkins, vicar of Ledwardine.

Here, a prominent Hereford estate agent and enthusiastic rock climber, Peter Portis, has plummeted to his death from one of the peaks of a Wye Valley rock formation known as The Seven Sisters. A tragic accident? Perhaps. A parallel plot develops. In another parish, the vicar – a former TV actor called Arlo Ripley – has asked Merrily for help. One of his flock has reported seeing the spectre of a young girl and isn’t sure what to do. Enter, stage left, William Wordsworth. Not in person, obviously, but on a visit to the Wye Valley, the poet apparently met a young girl who claimed she could communicate with her dead siblings. The result was his poem We are Seven. That, and Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey are the spine of this novel. Click the titles, and you will see the full texts of the poems. The girl who has entered the life of Maya Madden – a TV producer renting a cottage in the village of Goodrich – seems to be one and the same as Wordsworth’s muse.

Enter, stage right, another Hereford copper, David Vaynor. Nicknamed ‘Darth’ by his boss Frannie Bliss, he is an unusual chap. For starters, he has a PhD in English literature, and his thesis was based on Wordsworth’s time in Herefordshire. To add to the strangeness, while he was researching his work, he went into what is known as King Arthur’s Cave, a natural cavity in the rock close to where Portis met his end. While he was in there, he has a residual memory of sinking – exhausted – into what was a natural rock chair – and then being visited by a succubus.¹

Yes, yes, – the poor lad was tired, a bit hormonal and having bad dreams. But wait. As Vaynor is doing his job, and interviewing those who knew Portis, he meets his daughter in law, and she reminds him horribly of the woman he ‘met’ on that fateful afternoon in King Arthur’s Cave.

This has everything Merrily Watkins fans – and newcomers to the series – could want. A deep sense of unease, matchless atmosphere – the funeral held in fading light in a virtually disused churchyard, for example – the wonderful ambiguity of Rickman’s approach to the supernatural – we never actually see the phantoms, but we are aware that other people have – the wonderful repertory company of characters who interact so well, and also a deep sense that the past is never far away. There is also a palpable sense of irony that ‘the fever of the world’ is not just a metaphor from a Wordsworth poem, but was actually happening as the coronavirus took hold.

The Fever of the World is published by Corvus/Atlantic books and is out now.

¹A succubus is a demon or supernatural entity in folklore, in female form, that appears in dreams to seduce men, usually through sexual activity.

There are no honourable mentions here, because, (if you’ve been good) you will have seen them all in the previous four posts. Regular readers of this blog, and those who read my interviews, reviews and features on Crime Fiction Lover, will know that I am a massive fan of Phil Rickman’s books and, in particular, the series featuring the thoroughly modern, but often conflicted, parish priest, Merrily Watkins. She is one of the most intriguing and best written characters in modern fiction, but Rickman (left) doesn’t stop there. He has created a whole repertory company of supporting characters who range in style and substance from the wizened sage Gomer Parry – he of the roll-up fags and uncanny perception (often revealed as he digs holes for septic tanks) – to the twin-set and pearls imperturbability of the Bishop’s secretary, Sophie. In between we have the fragile genius of Merrily’s boyfriend, musician Lol Robinson, the maverick Scouse policeman Frannie Bliss and, of course, Merrily’s adventurous daughter Jane, for whom the soubriquet ‘Calamity” would fit nicely, such is her propensity to go where both angels – and her anxious mother – fear to tread.

There are no honourable mentions here, because, (if you’ve been good) you will have seen them all in the previous four posts. Regular readers of this blog, and those who read my interviews, reviews and features on Crime Fiction Lover, will know that I am a massive fan of Phil Rickman’s books and, in particular, the series featuring the thoroughly modern, but often conflicted, parish priest, Merrily Watkins. She is one of the most intriguing and best written characters in modern fiction, but Rickman (left) doesn’t stop there. He has created a whole repertory company of supporting characters who range in style and substance from the wizened sage Gomer Parry – he of the roll-up fags and uncanny perception (often revealed as he digs holes for septic tanks) – to the twin-set and pearls imperturbability of the Bishop’s secretary, Sophie. In between we have the fragile genius of Merrily’s boyfriend, musician Lol Robinson, the maverick Scouse policeman Frannie Bliss and, of course, Merrily’s adventurous daughter Jane, for whom the soubriquet ‘Calamity” would fit nicely, such is her propensity to go where both angels – and her anxious mother – fear to tread.

In All Of a Winter’s Night a young man has been killed in a mysterious car crash, and his funeral attracts bitterly opposed members of the same family. Merrily tries to preside over potential chaos, and her efforts to ensure that Aidan Lloyd rest in peace are not helped when his body is disinterred, dressed in his Morris Man costume, and then clumsily reburied. Rickman adds to the mix the very real and solid presence of the ancient church at Kilpeck, with its pagan – and downright vulgar (in some eyes) carvings. The climax of the novel comes when Merrily tries to conduct a service of remembrance in the tiny church. What happens next is, literally, breathtaking – and one of the most terrifying and disturbing chapters of any novel you will read this year or next. With its memorable mix of crime fiction, menacing landscape, human jealousy, sinister tradition and pure menace, All Of a Winter’s Night is my book of 2017.

In All Of a Winter’s Night a young man has been killed in a mysterious car crash, and his funeral attracts bitterly opposed members of the same family. Merrily tries to preside over potential chaos, and her efforts to ensure that Aidan Lloyd rest in peace are not helped when his body is disinterred, dressed in his Morris Man costume, and then clumsily reburied. Rickman adds to the mix the very real and solid presence of the ancient church at Kilpeck, with its pagan – and downright vulgar (in some eyes) carvings. The climax of the novel comes when Merrily tries to conduct a service of remembrance in the tiny church. What happens next is, literally, breathtaking – and one of the most terrifying and disturbing chapters of any novel you will read this year or next. With its memorable mix of crime fiction, menacing landscape, human jealousy, sinister tradition and pure menace, All Of a Winter’s Night is my book of 2017.

and Selena’s qualifications as a psychologist made them the go-to people for corporations and wealthy families who had fallen foul of the highly lucrative business of international kidnapping. But then, on a blisteringly hot morning in Brasilia, it all went badly wrong. Selena went shopping for children’s toys prior to her addressing a meeting of fellow professionals in the afternoon. While she was selecting gifts for their little daughters, the bad guys attacked the hotel and conference centre, shooting, bombing and delivering a stark message. “You may think you are smarter than us, but look at the body count, and then tell us how clever you are.”

and Selena’s qualifications as a psychologist made them the go-to people for corporations and wealthy families who had fallen foul of the highly lucrative business of international kidnapping. But then, on a blisteringly hot morning in Brasilia, it all went badly wrong. Selena went shopping for children’s toys prior to her addressing a meeting of fellow professionals in the afternoon. While she was selecting gifts for their little daughters, the bad guys attacked the hotel and conference centre, shooting, bombing and delivering a stark message. “You may think you are smarter than us, but look at the body count, and then tell us how clever you are.”

One of the many delights of this excellent novel is that Finna Hale and Leah Mackay are brother and sister. Finn has leap-frogged his sister in the promotion stakes, despite her evident superiority – evident, that is, to us readers, but not the local constabulary personnel department. Kavanagh plays the relationship between the siblings with the touch of a concert violinist. There are all manner of clever nuances and deft little touches which enhance the narrative.

One of the many delights of this excellent novel is that Finna Hale and Leah Mackay are brother and sister. Finn has leap-frogged his sister in the promotion stakes, despite her evident superiority – evident, that is, to us readers, but not the local constabulary personnel department. Kavanagh plays the relationship between the siblings with the touch of a concert violinist. There are all manner of clever nuances and deft little touches which enhance the narrative.

The Reverend Merrily Watkins, who was first brought to life by Phil Rickman in The Wine of Angels in 1998, is, on one level, your average workaday Anglican parish priest. For starters she is a woman, and the Church’s own website tells us that while male ordinations are declining, those of women are increasing rapidly. Secondly, Merrily faces a declining congregation in her Herefordshire village – just like hundreds of other parishes up and down the country. Thirdly, she observes – at a distance, admittedly – the continuing friction between modernising progressives and the traditionalists in the hierarchy of the Church of England.

The Reverend Merrily Watkins, who was first brought to life by Phil Rickman in The Wine of Angels in 1998, is, on one level, your average workaday Anglican parish priest. For starters she is a woman, and the Church’s own website tells us that while male ordinations are declining, those of women are increasing rapidly. Secondly, Merrily faces a declining congregation in her Herefordshire village – just like hundreds of other parishes up and down the country. Thirdly, she observes – at a distance, admittedly – the continuing friction between modernising progressives and the traditionalists in the hierarchy of the Church of England.