I can’t think of another modern crime writer who does truly despicable villains quite like Nick Oldham. His years policing the semi-derelict housing estates behind the candy-floss, donkey rides and silly hat persona of Blackpool’s seafront taught him that the feral inhabitants thrown up by these estates are not victims of social injustice or poverty; neither are they the product of years of exploitation by cruel capitalists. No. In short, they are absolute bastards, and no amount of hugging by wet-behind-the-ears social workers will make them anything else. In Death Ride, Oldham introduces us to as vile a group of criminals as he has ever created. Led by Lenny Lennox, they are ruthless predators; pickpocketing, catalytic converters, dog-napping, abduction, sexual assault – and murder – frame their lives.

We meet them at a country fair in retired copper Henry Christie’s home village, Kendleton – high on the Lancashire moors – where he runs the local pub. While Lenny Lennox serves burgers from his catering van, his son and three other youngsters pick pockets, steal cameras and strip high end vehicles of their valuable exhaust systems. Ernest Lennox, however has gone a bit further, and abducted a teenage girl who resisted his advances, and to cover up his son’s stupidity Lennox senior has to take drastic action.

Christie has recently been used as a civilian consultant by his former employers, and his last case ended with him being brutally stabbed and left for dead. When the hunt for the missing girl – Charlotte Kirkham – becomes a race against time, Christie, partly crippled by his knife wounds, is drawn into the hunt. I am reminded of the words of Tennyson in his magnificent poem Ulysses:

“Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

In rather blunter terms, Oldham writes:

“If Henry was honest with himself, he felt the urge to drag Lennox out of the burger van and smash his face again, just for old times’ sake, even though he knew he didn’t have the physicality to put that desire into action.

The Lennox gang create carnage in Christie’s life – and the lives of those he loves – but about three quarters of the way through the book, there is an abrupt change of scene, and we are reunited with two characters from Christie’s past – FBI agent Karl Donaldson and ex special forces maverick, Steve Flynn. They say that revenge is both sweet and best served cold. Suffice it to say that Henry Christie enjoys his gelato.

The Henry Christie books have always had plenty of action and their fair share of grit and gore, but on this occasion, be warned. Nick Oldham goes into Derek Raymond territory here, with a dark and terrifying novel which explores the depths of human malice and depravity. Death Ride is published by Severn House and will be available from 7th March. For more about Nick Oldham and the Henry Christie books, click the image below.

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

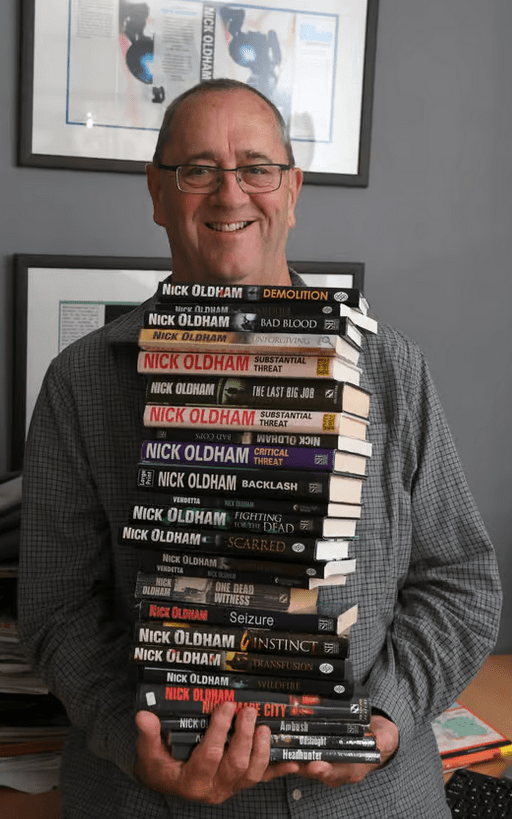

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants. Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

The 1985 episode links crucially with the second part of the book which is firmly in present day Covid-restricted Lancashire, complete with masks and elbow bumps. A teenage boy who was the object of Christie’s near fatal pursuit – but then disappeared off the face of the earth – turns up again, but in an unexpected and deeply disturbing way.

The 1985 episode links crucially with the second part of the book which is firmly in present day Covid-restricted Lancashire, complete with masks and elbow bumps. A teenage boy who was the object of Christie’s near fatal pursuit – but then disappeared off the face of the earth – turns up again, but in an unexpected and deeply disturbing way.

ack in the day, before authors and their publishers trusted me with reviewing novels, I did what the vast majority of the reading public did – I either bought books when I could afford them or I went to the local library. I had a list of authors whose latest works I would grab eagerly, or take my place in the queue of library members who had reserved copies. In no particular order, anything by John Connolly, Jim Kelly, Phil Rickman, Frank Tallis, Philip Kerr, Mark Billingham, Christopher Fowler and Nick Oldham would be like gold dust.

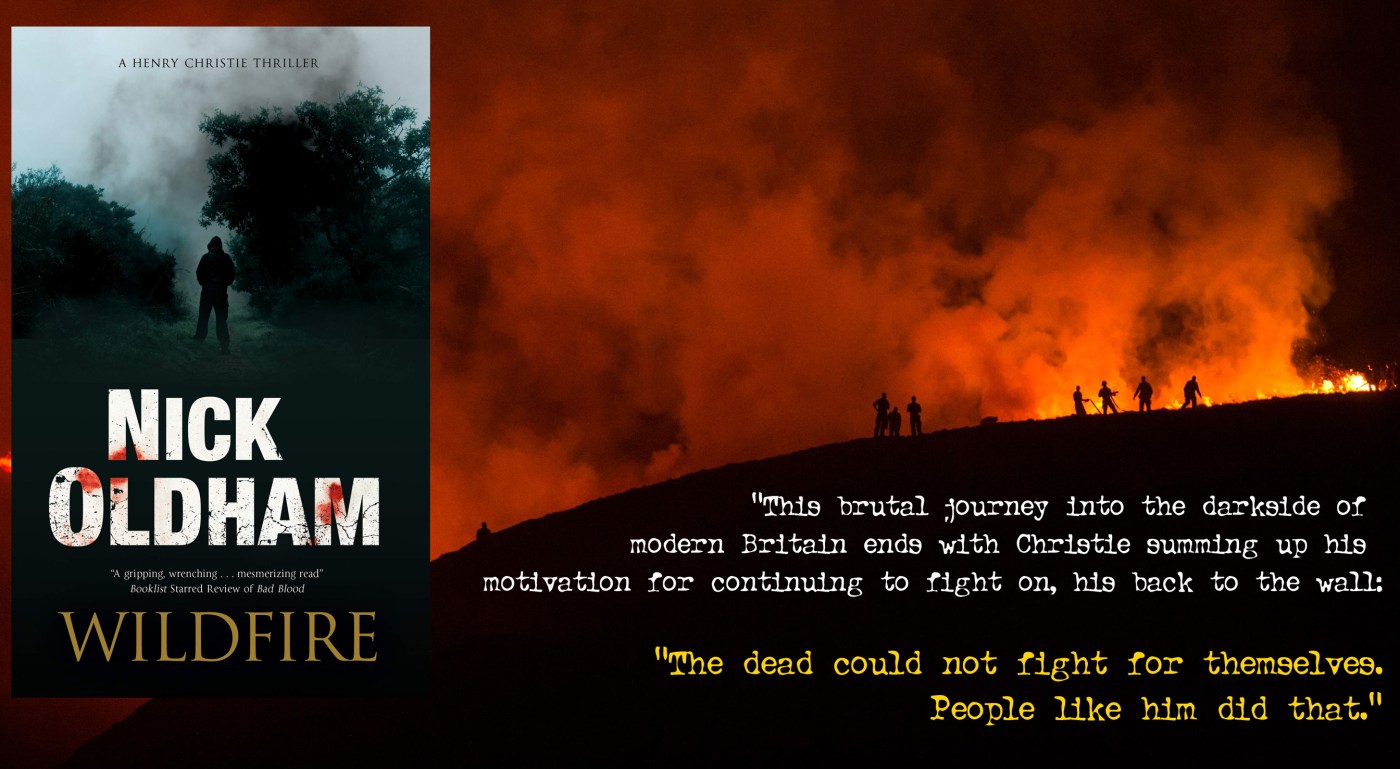

ack in the day, before authors and their publishers trusted me with reviewing novels, I did what the vast majority of the reading public did – I either bought books when I could afford them or I went to the local library. I had a list of authors whose latest works I would grab eagerly, or take my place in the queue of library members who had reserved copies. In no particular order, anything by John Connolly, Jim Kelly, Phil Rickman, Frank Tallis, Philip Kerr, Mark Billingham, Christopher Fowler and Nick Oldham would be like gold dust. Oldham’s Henry Christie was a particular favourite, as his adventures mixed excellent police procedure – thanks to Oldham’s career as a copper – a vulnerable and likeable hero, and an unflinching look at the mean and vicious streets of the Blackpool area in England’s north-west. Wildfire is the latest outing for Henry Christie, who has retired from the police and now runs a pleasant village pub set in the Lancashire hills.

Oldham’s Henry Christie was a particular favourite, as his adventures mixed excellent police procedure – thanks to Oldham’s career as a copper – a vulnerable and likeable hero, and an unflinching look at the mean and vicious streets of the Blackpool area in England’s north-west. Wildfire is the latest outing for Henry Christie, who has retired from the police and now runs a pleasant village pub set in the Lancashire hills.

ventually, the wildfires of both kinds are extinguished, at least temporarily, but not before Henry Christie is forced, yet again, to take a long hard look at himself in the mirror, and question if it was all worth the effort.

ventually, the wildfires of both kinds are extinguished, at least temporarily, but not before Henry Christie is forced, yet again, to take a long hard look at himself in the mirror, and question if it was all worth the effort. his brutal journey into the darkside of modern Britain ends with Christie summing up his motivation for continuing to fight on, his back to the wall:

his brutal journey into the darkside of modern Britain ends with Christie summing up his motivation for continuing to fight on, his back to the wall:

His resolve weakens, however, when he is visited by two of his more senior officers, his own Chief Constable and the newly appointed boss of the Central Yorkshire force, John Burnham. The Yorkshire police has suffered a disastrous inspection, and Burnham has been appointed to cleanse the Augean Stables.

His resolve weakens, however, when he is visited by two of his more senior officers, his own Chief Constable and the newly appointed boss of the Central Yorkshire force, John Burnham. The Yorkshire police has suffered a disastrous inspection, and Burnham has been appointed to cleanse the Augean Stables. Oldham (right) is a retired copper himself, so readers are guaranteed procedural details which are described with total authenticity, whether they be the smelly reality of unmarked police cars used for observation, complete with the detritus of discarded fast food wrappers and the inevitable flatulent consequences, and an intriguing – and quite scary – use for Blutac and two pence pieces.

Oldham (right) is a retired copper himself, so readers are guaranteed procedural details which are described with total authenticity, whether they be the smelly reality of unmarked police cars used for observation, complete with the detritus of discarded fast food wrappers and the inevitable flatulent consequences, and an intriguing – and quite scary – use for Blutac and two pence pieces.