I am delighted to say that my first review for 2021 is a new book by the reliably excellent story-teller, Chris Nickson. For those new to his books, he is a widely travelled former music journalist, who has rubbed shoulders with some of the big names in rock, but now pursues a rather more sedentary lifestyle in the Yorkshire city of Leeds. When he is not tending his treasured allotment, he writes historical novels, based around crime-solvers across the centuries, most of them based in Leeds.

I am delighted to say that my first review for 2021 is a new book by the reliably excellent story-teller, Chris Nickson. For those new to his books, he is a widely travelled former music journalist, who has rubbed shoulders with some of the big names in rock, but now pursues a rather more sedentary lifestyle in the Yorkshire city of Leeds. When he is not tending his treasured allotment, he writes historical novels, based around crime-solvers across the centuries, most of them based in Leeds.

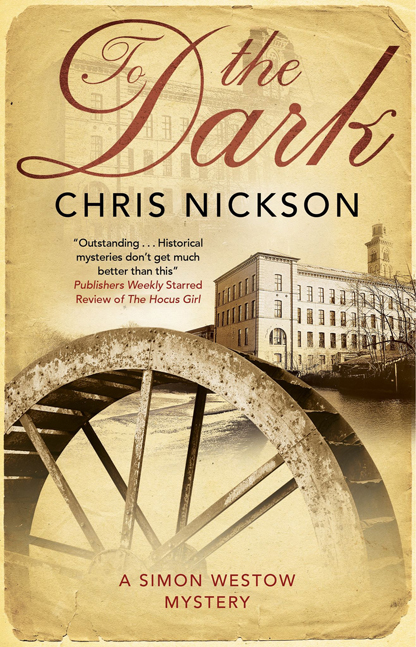

You can click the link to check out his late 19th century novels featuring the Leeds copper Tom Harper, but his latest book takes us back a little further, to Georgian times. Leeds is undergoing a violent transformation from being a bustling, but still largely bucolic centre of the wool trade, to a smoky, clattering child of the Industrial Revolution.

There are fortunes to be made in Leeds, but crime is still crime, and Simon Westow is known as a thief-taker. Remember, this is before the emergence of a regular police force, and what law there is is enforced by (usually incompetent) town constables, and men like Westow who will recover stolen property – for a fee.

Westow is a man who has survived a brutal upbringing as an institutionalised orphan, and there is not a Leeds back alley, courtyard or row of shoddily-built cottages that he doesn’t know. He doesn’t work alone. He has an unusual ally. We know her only as Jane. Like Westow, this young woman has survived an abusive childhood, but unlike Westow – who isn’t afraid to use his fists, but is largely peaceable – Jane is a killer. She carries a razor sharp knife, and uses it completely without conscience if she is threatened by men who remind her of the degradation she suffered when younger.

Westow is a man who has survived a brutal upbringing as an institutionalised orphan, and there is not a Leeds back alley, courtyard or row of shoddily-built cottages that he doesn’t know. He doesn’t work alone. He has an unusual ally. We know her only as Jane. Like Westow, this young woman has survived an abusive childhood, but unlike Westow – who isn’t afraid to use his fists, but is largely peaceable – Jane is a killer. She carries a razor sharp knife, and uses it completely without conscience if she is threatened by men who remind her of the degradation she suffered when younger.

When a petty criminal is found dead in a drift of frozen snow, Westow frets that he will be linked with the murder as, only a week or so earlier, he had completed a lucrative assignment that involved returning to their owner stolen goods that had come into the hands of the dead man. Instead of being harassed by the lazy and vindictive town constable, Westow is asked to try to solve the crime. It seems that two aristocratic officers from the town’s cavalry barracks might be involved with the killing, and this sets Westow a formidable challenge, as the soldiers are very much a law unto themselves. Meanwhile a notebook has been found which is connected to one of murdered criminal’s associates, but it reveals little, as it is mostly in code. Someone cracks the cipher for Westow, but he is little the wiser, especially when the text contains the enigmatic phrase ‘To The Dark.’

The discovery of a stolen handwritten Book of Hours, potentially worth thousands of gold sovereigns, further complicates the issue for Westow, and when the seemingly invincible Jane suffers a crippling injury, his eyes and ears on the Leeds streets are severely diminished. Still, the significance of ‘To The Dark’ escapes him, and when his life and those of his wife and children are threatened he is forced to face the fact that this seemingly intractable mystery may be beyond his powers to solve.

As ever with Chris Nickson’s novels we smell the streets and ginnels of Leeds and breathe in its heady mixture of soot, sweat and violence. In one ear is the deafening and relentless collision of iron and steel in the factories, but in the other is the still, small voice of the countryside, just a short walk from the bustle of the town. Nickson is a saner version of The Ancient Mariner. He has a tale to tell, and he will not let go of your sleeve until it is told. To The Dark is published by Severn House and is out now.

eing a middle class British father and grandfather, the concept of abandoning a newly born baby is totally beyond my experience of life and (the fault is perhaps mine) my comprehension. The fact is, however, that since Adam had his way with Eve, biology has trumped human intention, and babies have come into the world unloved and unwanted. Thankfully, there have been charitable institutions over the centuries which have done their best to provide some kind of home for foundlings. Abandoning babies is not something consigned to history: modern Germany has its Babyklappe, and Russia its Колыбель надежды – literally hatches – rather like an old fashioned bank deposit box – built into buildings where babies can be left. Back in time, Paris had its Maison de la Couche pour les Enfants Trouvés while in Florence the Ospedale degli Innocenti is one of the gems of early Renaissance architecture. London had its Foundling Hospital, and it is the centre of The Foundling, the new novel by Stacey Halls.

eing a middle class British father and grandfather, the concept of abandoning a newly born baby is totally beyond my experience of life and (the fault is perhaps mine) my comprehension. The fact is, however, that since Adam had his way with Eve, biology has trumped human intention, and babies have come into the world unloved and unwanted. Thankfully, there have been charitable institutions over the centuries which have done their best to provide some kind of home for foundlings. Abandoning babies is not something consigned to history: modern Germany has its Babyklappe, and Russia its Колыбель надежды – literally hatches – rather like an old fashioned bank deposit box – built into buildings where babies can be left. Back in time, Paris had its Maison de la Couche pour les Enfants Trouvés while in Florence the Ospedale degli Innocenti is one of the gems of early Renaissance architecture. London had its Foundling Hospital, and it is the centre of The Foundling, the new novel by Stacey Halls. Bess Bright is a Shrimp Girl. Her father gets up at the crack of dawn to buy Essex shrimps from Billingsgate Market, and Bess puts the seafood in the brim of a broad hat and, clutching a tiny tankard to measure them out, she walks the streets of

Bess Bright is a Shrimp Girl. Her father gets up at the crack of dawn to buy Essex shrimps from Billingsgate Market, and Bess puts the seafood in the brim of a broad hat and, clutching a tiny tankard to measure them out, she walks the streets of  elling shrimps from the brim of your hat is not an occupation destined to provide sufficient funds to keep a growing child, and so Bess presents herself and baby Clara at

elling shrimps from the brim of your hat is not an occupation destined to provide sufficient funds to keep a growing child, and so Bess presents herself and baby Clara at

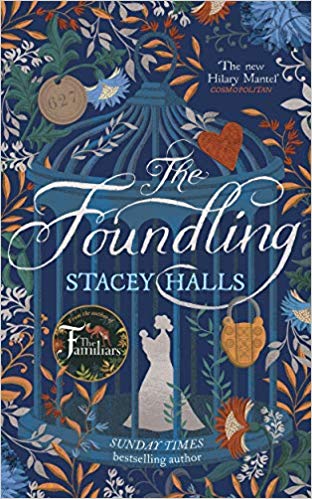

ow – and where – Bess finds her missing daughter is for you to discover, but I promise that The Foundling is ingenious, delightful, and the author’s skills as a storyteller are magnetic. The attention to detail and the period authenticity are things to be wondered at, but what elevates this novel above the humdrum is how Stacey Halls conjures up our sheer emotional investment in the characters, each one beautifully observed. Art lovers will recognise the painter – and the title – of the picture below and, were he alive to read it, the great observer of London life would thoroughly approve of The Foundling, which is published by Manilla Press and is out on

ow – and where – Bess finds her missing daughter is for you to discover, but I promise that The Foundling is ingenious, delightful, and the author’s skills as a storyteller are magnetic. The attention to detail and the period authenticity are things to be wondered at, but what elevates this novel above the humdrum is how Stacey Halls conjures up our sheer emotional investment in the characters, each one beautifully observed. Art lovers will recognise the painter – and the title – of the picture below and, were he alive to read it, the great observer of London life would thoroughly approve of The Foundling, which is published by Manilla Press and is out on

This, then, is the England of Handel and Hogarth (at least he was English) and the looming threat from the Jacobites north of the border. Author Robin Blake, (left) however resists the easy win of setting his story in the bustle of London. Instead, he takes us to the town of Preston, sitting on the banks of the River Ribble in Lancashire.

This, then, is the England of Handel and Hogarth (at least he was English) and the looming threat from the Jacobites north of the border. Author Robin Blake, (left) however resists the easy win of setting his story in the bustle of London. Instead, he takes us to the town of Preston, sitting on the banks of the River Ribble in Lancashire. The investigations carried out by Cragg and Fidelis reveal a growing schism between the tanners and the wealthy men of property who run the town’s affairs. The leather workers are an inward looking community. This state is mostly driven by the fact that they live and work alongside the noisome waste materials – mostly faeces and urine – which are essential to the tanning process, and therefore most local people literally turn up their noses at the tanners. The burgesses and council-men of Preston, on the other hand, have their eyes on what they believe to be an acre or so of valuable land – ripe for redevelopment – currently occupied by the tannery.

The investigations carried out by Cragg and Fidelis reveal a growing schism between the tanners and the wealthy men of property who run the town’s affairs. The leather workers are an inward looking community. This state is mostly driven by the fact that they live and work alongside the noisome waste materials – mostly faeces and urine – which are essential to the tanning process, and therefore most local people literally turn up their noses at the tanners. The burgesses and council-men of Preston, on the other hand, have their eyes on what they believe to be an acre or so of valuable land – ripe for redevelopment – currently occupied by the tannery.