Perhaps there’s a PhD to be written on the character of Madame Maigret, and none of the TV or film versions have made much of her, but here, at least for a while, she takes centre stage, in rather an unfortunate fashion. A young man, terribly nervous and ill-at-ease, arrives at their apartment, 132 Boulevard Richard Lenoir, asking to speak to the great man. Perhaps because he seems shy and inoffensive, she lets him in to wait while she finishes cooking lunch. A little while later, she breaks with their normal convention and telephones her husband at work. Hesitantly, she explains what has happened and, shamefaced, saying that the young man has now left, but she believes he has taken a revolver – presented to Maigret by the FBI – some years earlier. The revolver may seem to be ceremonial, as it is engraved with Maigret’s name, but it is far from a museum piece. It is a Smith and Wesson .45 and a very powerful agent of death in the wrong hands.

In what appears to be a separate strand of the plot, we learn that the Maigrets have recently dined with a long-standing friend, Dr Pardon, and that another guest – Lagrange – who was apparently very anxious to meet the celebrated policeman, failed to show up. When they visit Lagrange at his home, they find a man who appears to be extremely ill. Pardon confides in Maigret that Lagrange is something of a problem patient. Bedridden though he may appear to be, it transpires that he had enough strength to hire a taxi late the previous evening and, with the driver’s help, convey a heavy trunk to the left luggage office of the Gare du Nord. There is a very satisfying ‘click-clunk’ when it emerges that the young man who took Maigret’s revolver is none other than Alain, the sick man’s son. And in the trunk? A dead body, naturally, and it is that of André Delteil, a prominent – and controversial – politician, shot dead with a small calibre handgun.

Lagrange, when questioned, descends into a state of paranoia and behaves like a feverish child. Maigret cannot decide if this is genuine, or an attempt to defer the inevitable investigation into the corpse in the trunk. Playing safe, he sends the man to hospital. But what links the murdered politician, the babbling Lagrange – and his fugitive son? Simenon comes up with a very elegant – and deadly – connection in the shape of a wealthy socialite called Jeanne Debul who collects rich men like some people collect stamps. He uncovers a deeply unpleasant melange of blackmail, obsession and greed and concludes that Alain Lagrange is convinced that his father’s downfall can be laid at the door of Madame Debul. And he is at large, with Maigret’s revolver and a box of recently bought ammunition.

Maigret is not best pleased to learn that Jeanne Debul has flown to London, followed – on the next flight – by Alain Lagrange. It’s a rotten job, but someone has to do it, and Maigret follows the socialite and her would-be assassin to London, where he books into the same hotel as Madame Debul – The Savoy, no less. Helped – and hindered – by his Scotland Yard counterparts, our man awaits the collision of hunter and hunted, and this section of the story is a delightful flourish by Simenon where, via his great creation, he describes every little irritation and frustration that an urbane Frenchman could possibly encounter in the buttoned-up world of 1950s London.

As ever with Simenon, this story is a masterpiece of brevity – just 150 pages – and where lesser writers might take a page or more to describe a person, an atmosphere or a situation, he does the job in a paragraph. This edition of Maigret’s Revolver (first published in 1952), translated by Siân Reynolds, is one of the new Penguin Modern Classics and will be available on 5th October

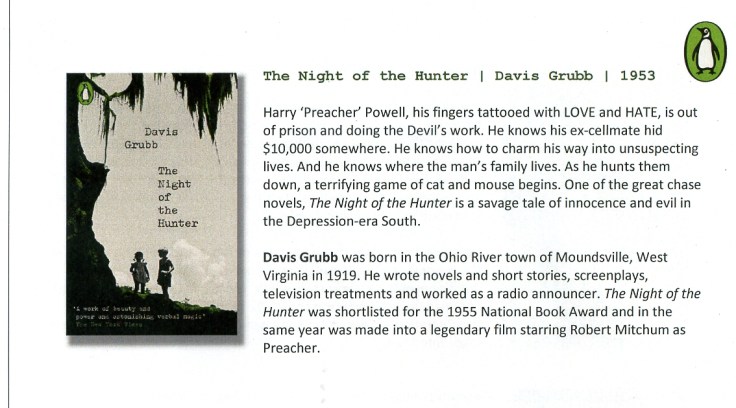

Whatever other qualities the book may have, the name of the town in which it is set gets first prize for the most sinister sounding location – Whistling Ridge. You just know that this is a town with dark secrets and simmering tensions that have festered for generations. Throw in a charismatic hellfire preacher who seems to have the town in his thrall, a girl who inexplicably disappeared into the woods, and a mysterious outsider who fascinates the young folk but arouses deep resentment in their parents – and you have a crackerjack thriller. Published by Doubleday, Tall Bones is

Whatever other qualities the book may have, the name of the town in which it is set gets first prize for the most sinister sounding location – Whistling Ridge. You just know that this is a town with dark secrets and simmering tensions that have festered for generations. Throw in a charismatic hellfire preacher who seems to have the town in his thrall, a girl who inexplicably disappeared into the woods, and a mysterious outsider who fascinates the young folk but arouses deep resentment in their parents – and you have a crackerjack thriller. Published by Doubleday, Tall Bones is  A husband disappears, leaving only a one word scribbled note that says “

A husband disappears, leaving only a one word scribbled note that says “ School stories, at least those written for younger readers, were once ‘a thing’ but something of a rarity these days. This book, the third in a series, is aimed at adult readers, and is set in 1957 within a boys’ boarding school in Yorkshire, and is centred on a Jewish teenager who is made to feel an outcast by senior boys who feel he is not “

School stories, at least those written for younger readers, were once ‘a thing’ but something of a rarity these days. This book, the third in a series, is aimed at adult readers, and is set in 1957 within a boys’ boarding school in Yorkshire, and is centred on a Jewish teenager who is made to feel an outcast by senior boys who feel he is not “ Sarah Pearse’s previous (and debut) novel

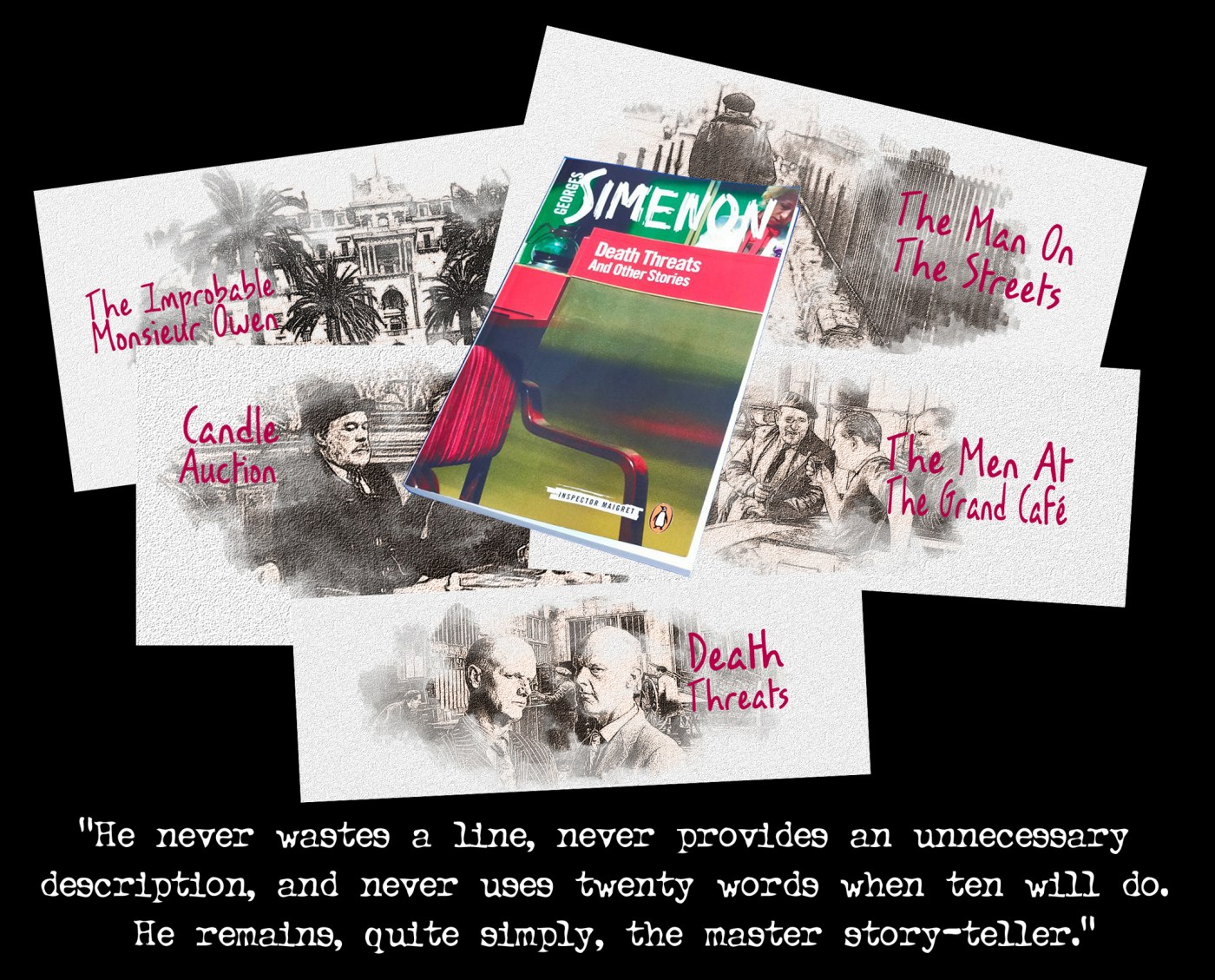

Sarah Pearse’s previous (and debut) novel  Penguin are publishing new translations of Simenon’s stories. I’ve reviewed

Penguin are publishing new translations of Simenon’s stories. I’ve reviewed

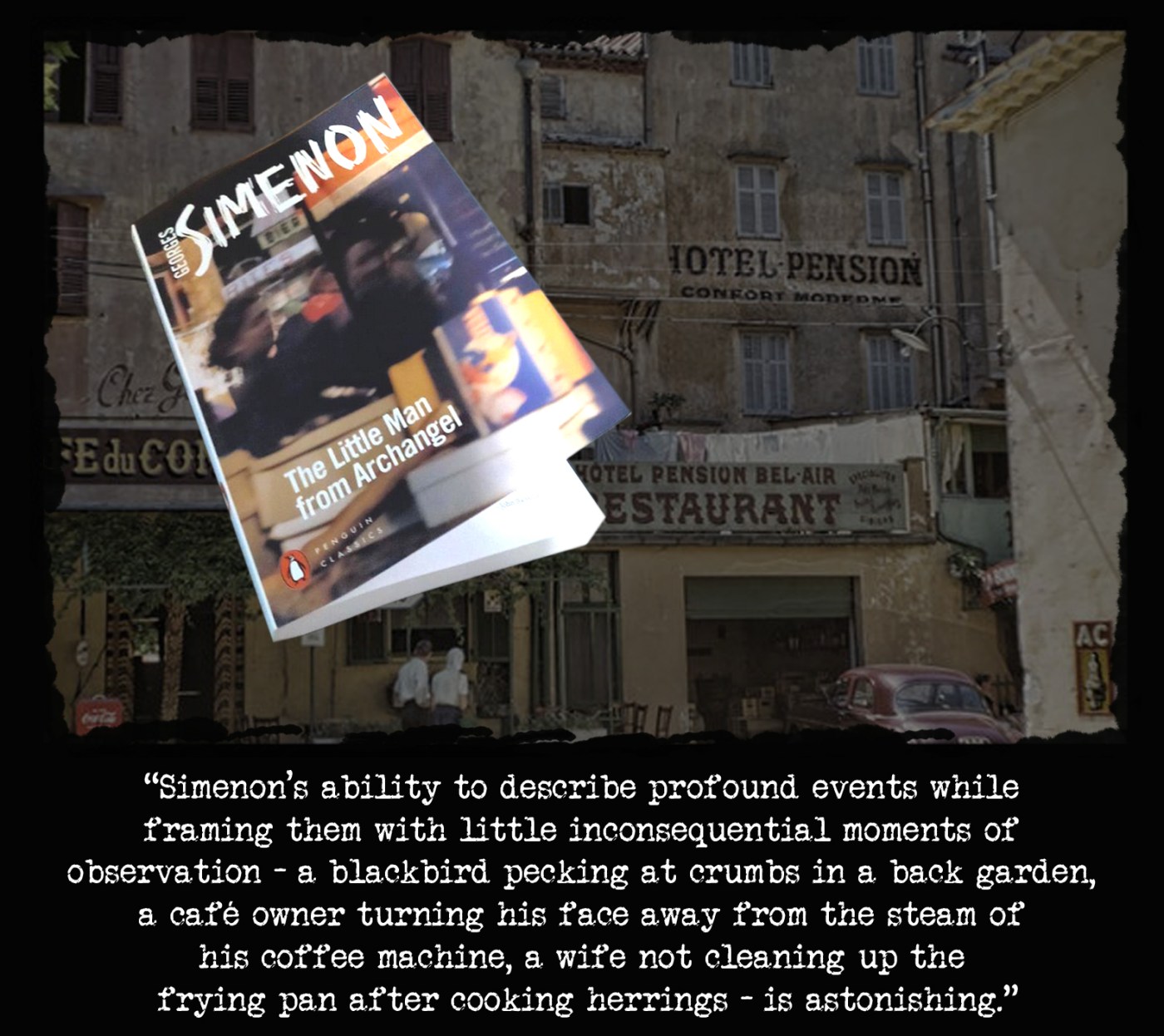

We are in an anonymous little town in the Berry region of central France, and it is the middle years of the 1950s. Jonas Milk is a mild-mannered dealer in second hand books. His shop, his acquaintances, the c

We are in an anonymous little town in the Berry region of central France, and it is the middle years of the 1950s. Jonas Milk is a mild-mannered dealer in second hand books. His shop, his acquaintances, the c Jonas Milk has a wife. Two years earlier he had converted to Catholicism and married Eugénie Louise Joséphine Palestri – Gina – a voluptuous and highly sexed woman sixteen years his junior. No doubt the frequenters of the Vieux-Marché have their views on this marriage, but they are polite enough to keep their opinions to themselves, at least when Jonas is within earshot. But then Gina disappears, taking with her no bag or change of clothing. The one thing she does take, however, is a selection of a very valuable stamp collection that Jonas has put together over the years, not through major purchases from dealers, but through his own obsessive examination of relatively commonplace stamps, some of which turn out to have minute flaws, thus making their value to other collectors spiral to tens of thousands of francs.

Jonas Milk has a wife. Two years earlier he had converted to Catholicism and married Eugénie Louise Joséphine Palestri – Gina – a voluptuous and highly sexed woman sixteen years his junior. No doubt the frequenters of the Vieux-Marché have their views on this marriage, but they are polite enough to keep their opinions to themselves, at least when Jonas is within earshot. But then Gina disappears, taking with her no bag or change of clothing. The one thing she does take, however, is a selection of a very valuable stamp collection that Jonas has put together over the years, not through major purchases from dealers, but through his own obsessive examination of relatively commonplace stamps, some of which turn out to have minute flaws, thus making their value to other collectors spiral to tens of thousands of francs.